Raritan Landscape Reemergence: Awakening Lyell’s Brook Through Dance

Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP) and Rock Dance Collective are proud to present “Raritan Landscape Reemergence: Awakening Lyell’s Brook Through Dance”, a short filmed movement rhapsody that educates and engages audiences around connection and access to the Raritan River in central New Jersey as part of #lookfortheriver. This project features world premiere choreography by Rock Dance Collective artistic directors Cleo Mack and Blair Ritchie, building off of their decade of work in the region creating sensory experiences using sculpture, sound, and movement for audiences of all ages. The movement based work was filmed along the Lyell’s Brook corridor in the Lower Raritan Watershed and culminates at the newly installed #lookfortheriver sculptural FRAME at Boyd Park, in New Brunswick, NJ. The movement piece and frame work in concert to showcase the potential for new interactions between people, the built environment, and the natural landscape.

This project features world premiere choreography by Rock Dance Collective artistic directors Cleo Mack and Blair Ritchie, building off of their decade of work in the region creating sensory experiences using sculpture, sound, and movement for audiences of all ages. The movement based work was filmed along the Lyell’s Brook corridor in the Lower Raritan Watershed and culminates at the newly installed #lookfortheriver sculptural FRAME at Boyd Park, in New Brunswick, NJ. The movement piece and frame work in concert to showcase the potential for new interactions between people, the built environment, and the natural landscape.

The piece was filmed and edited and released two weeks prior to City of Water Day 2022 as part of outreach for City of Water Day in-person events throughout the New York/New Jersey Harbor Estuary. Rock Dance Collective works in both nontraditional and traditional spaces, responding to societal and environmental stimuli to create meaningful works. In addition to the filmed based work, Rock Dance Collective created an epilogue that was performed live at the Lower Raritan Watershed City of Water Day in-person convening at New Brunswick’s Boyd Park.

This project is part of a multi-year collaboration between community partners, non-profit civic science organizations, city agencies, and socially engaged artists to create impact oriented artistic response projects that advance strategic planning goals of the Lower Raritan Watershed. In 2017 Rock Dance Collective, in partnership with coLAB Arts and LRWP, created an original piece on the Raritan River waterfront titled A Watershed Moment showcasing the historic and contemporary usages of the largest river in NJ.

LRWP and Rock Dance Collective continue their collaboration through active planning of a “Watershed Run-Off” project which will feature an environmental “smart mob” land contour and stormwater flows demonstration project for the City of New Brunswick, NJ. “The Run Off” is both a community stormwater planning exercise and a collaborative public performance. It is designed to engage City residents and those who work, attend school, visit and/or recreate in New Brunswick in stormwater management planning processes, interspersed with public performance events.

Grant funding has been provided by the Middlesex County Board of County Commissioners through a grant award from Middlesex County Cultural and Arts Trust Fund.

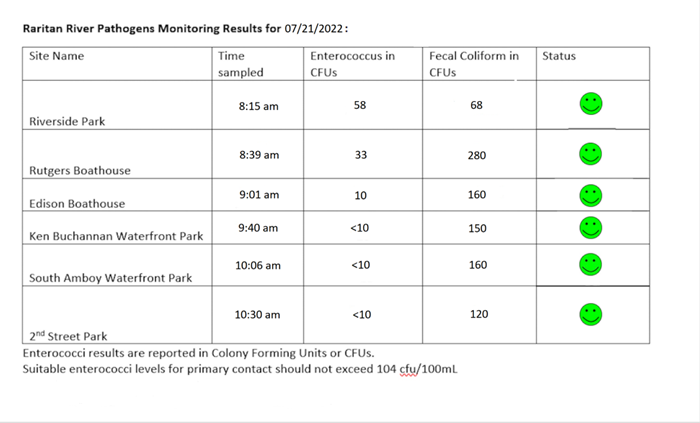

July 21, 2022 Raritan Pathogens Results

By LRWP Monitoring Outreach Coordinator Jocelyn Palomino

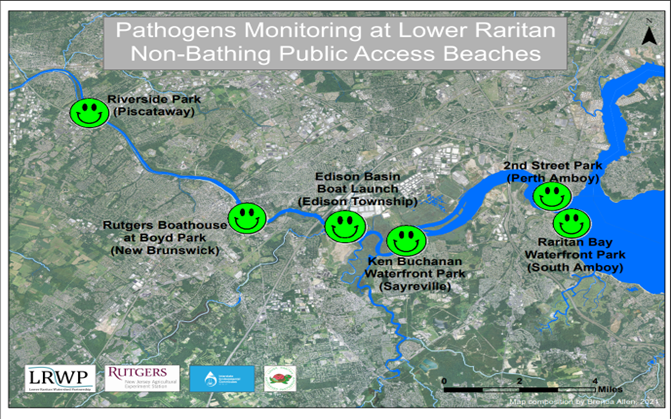

The Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County run a volunteer pathogens monitoring program from May to September every Summer. On Thursdays we collect water quality samples at 6 non-bathing public access beaches along the Raritan River, and report the results on Friday afternoons.

Our current drought conditions mean it’s another full set of green smiley faces for our Raritan River for July 21, 2022! Pathogens results run by the Interstate Environmental Commission (IEC) lab suggest Enterococcus bacteria levels below the federal water quality standard for recreation at ALL of our sites (indicated by lots of “green smiley faces” on the map below). These sites include Riverside Park (Piscataway), Rutgers Boathouse (New Brunswick), Edison Boat Ramp, Ken Buchanan Waterfront Park (Edison), South Amboy Waterfront Park, and 2nd Street Park (Perth Amboy).

Suitable levels for primary contact should not exceed 104 cfu/100mL. Per the EPA’s federal water quality standard for CFU primary contact, Pathogens/Enterococci levels are used as indicators of the possible presence of disease-causing bacteria in recreational waters. Sources of bacteria include Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), improperly functioning wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff, leaking septic systems, animal carcasses, and runoff from manure storage areas. Such pathogens may pose health risks to people fishing and swimming in a water body.

As always, many thanks to the Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County and Interstate Environmental Commission for their partnership, and to our amazing volunteers this week! See here for more information on our pathogens monitoring program.

July 14, 2022 Raritan Pathogens Results

By Monitoring Outreach Coordinator Jocelyn Palomino

The Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County

run a volunteer pathogens monitoring program from May to September every Summer. On

Thursdays we collect water quality samples at 6 non-bathing public access beaches along the

Raritan River, and report the results on Friday afternoons. Our pathogens results for July 14, 2022 suggest Enterococcus bacteria levels below the federal water quality standard for recreation at the majority of our sites indicated by a “green smiley face” on the map below. These sites include Riverside Park (Piscataway), Rutgers Boathouse (New Brunswick), Ken Buchanan Waterfront Park (Edison), South Amboy Waterfront Park, and 2nd Street Park (Perth Amboy). Enterococcus bacteria levels at our Edison Boat Ramp site (indicated by a “red frown face” on the map) were higher than the federal water quality standard and these waters are not safe to use for recreation.

Suitable levels for primary contact should not exceed 104 cfu/100mL. Per the EPA’s federal water quality standard for CFU primary contact, Pathogens/Enterococci levels are used as indicators of the possible presence of disease-causing bacteria in recreational waters. Sources of bacteria include Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), improperly functioning wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff, leaking septic systems, animal carcasses, and runoff from manure storage areas. Such pathogens may pose health risks to people fishing and swimming in a water body.

Big thanks to our partners Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County and Interstate Environmental Commission, and to our crew of monitoring volunteers this week! See here for more information on our pathogens monitoring program. As always, if you choose to recreate on the water this weekend, stay safe, and be sure to wash your hands!

July 7, 2022 Raritan Pathogens Results

The Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County run a volunteer pathogens monitoring program from May to September every Summer. On Thursdays we collect water quality samples at 6 non-bathing public access beaches along the Raritan River, and report the results on Friday afternoons. Our pathogens results for our Thursday July 7 monitoring suggest waters below the federal threshold for the Enterococcus bacteria at three sites: Piscataway, New Brunswick and South Amboy (indicated on the map below with green smiley faces). Suitable levels for primary contact should not exceed 104 cfu/100mL and these sites are below 104 colony forming units of Enterococci per 100mL. Per the EPA’s federal water quality standard for CFU primary contact, Pathogens/Enterococci levels are used as indicators of the possible presence of disease-causing bacteria in recreational waters. Waters at two of our sites, Ken Buchanan Waterfront Park in Sayreville and 2nd Street Park in Perth Amboy exceeded the federal threshold for Enterococci. Such pathogens may pose health risks to people fishing and swimming in a water body, please recreate on the river at your own risk.

Unfortunately, we were not able to sample at our Edison site this week due to a fire at the adjacent Ken Buc Landfill Tuesday night. Middlesex County officials shut off the street and evacuated the area to avoid smoke inhalation. The fire was deemed to have started as a result of dry conditions and high temperatures.

Middlesex Police and Emergency responders at the Edison Basin Boat launch after Tuesday’s fire, Photo Credits: Andrew Gehman

Special thanks to the Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County and Interstate Environmental Commission for their partnership, and to our crew of monitoring volunteers this week! See here for more information on our pathogens monitoring program.

Julisa, Jason, and Jocelyn reunited for water monitoring at Riverside Park, Photo Credit: Andrew Gehman.

Cristian Sanlatte taking a closer look at a small deer we spotted across the river at the Rutgers Boathouse, Photo Credit: Andre Gehman

As Andrew G. goes out in the water to grab our sample, the rest of the team observes and gathers data from the South Amboy shore, Photo Credit: Cristian Sanlatte

Forever Summer

Article and photos by Joe Mish

An hour past dawn, the source of daylight was still obscured, as if the sun took a holiday and to honor its daily commitment, left its dimmest bulb to light the overcast mid-summer day. The reference points of shadow and light, used to mark the progress of the day, melted in compromise to obscure the passing of time. The temperature change from night to day, that stirs the wind, was on this day, unable to raise a breeze. The stillness and faded light were precursors to either rain or bright sun, as the saying goes, “a morning fog burns ere the noon”. Either way, this quintessential day defines the comfortable retreat into the natural harbor of deep summer.

Summer may be considered the offspring of the coordinated efforts of winter, spring and autumn. All preparation for a time, when new life and old, can strengthen and renew energy spent on elemental survival. Summer temperatures reduce the energy cost of life to maintain its existence. A savings that allows imagination and creativity to be directed to places other than immediate survival and to accumulate warm memories to heat the cold days of winter.

Stacking the wood shed with summer memories leaves no carbon footprint, is considered renewable and burns as an eternal flame.

Images of fresh picked bright red dewberries, packed in open top containers, cooling in the shade on a partially submerged rock, in a shallow flowing stream, elbows its way to mind when thoughts of summer arise. Enough berries to make two batches of jam, used to spread summer throughout the year, to share with family and friends.

The light show performed by fireflies, in the meadow along the river, is a legacy act that reaches back in time to childhood and a world of wonder. The purpose of the display, critical to the lightning bugs, is lost to the magic of tiny incandescent dots of yellow light, floating in the air above the darkened meadow. Magic is the honey tasted by the mind that initiates a journey of exploration. Its direction and depth as unpredictable as the choreography of this mid-summer light show.

Cattails are another image stored in the summer album of memories and trademarks. They grew in profusion along with swarms of mosquitoes which would forage for fresh blood when the sun went down. The summer heat would force neighbors outside to sit on porch steps, their presence betrayed in the darkness by the red glow of their burning cigarettes. The smoke was a deterrent to the mosquitoes, though restricted to smokers and anyone immediately downstream. Through primitive oral history, the legacy of burning sun dried cattails to keep mosquitoes at bay and safely light fireworks was kept alive. Cattails would be cut and brought home, muddy dungarees a dead giveaway that you roamed beyond the territory deemed safe by mom. The price of the harvest was a lecture from mom about being swallowed up by quicksand in the swamps. Cattails were picked while still slightly green as they could be stored over winter without losing their fluff. Courting danger, I would scramble up to the neighbor’s low, flat garage roof then take a running leap onto our peaked garage roof and set the cattails out to dry. After a week on the garage roof aged the cattails were ready to be lit and fend off the nightly aerial attack and defend the blood supply. Waving the burning cattail produced a cloud of smoke and unlike the anemic volume of cigarette smoke, could be directed upwind to wash over the legs or neck. Aside from the favorable aroma and copious smoke, you were sanctioned to play with fire and produce your own light show by waving the glowing brown magic wand, to create the illusion of circles, figure eights and words, which disappeared as if using invisible ink.

The images and memories contained in your summer archives are yours alone, collected at a moment when time stood still, indelibly etched, to be released when the right combination of summer conditions align.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author. Contact jjmish57@msn.com.

Spring Flows Seamlessly Into Summer

Article and photos by Joe Mish

The late spring rain continued without interruption into summer, though the shower only lasted two minutes.

Somewhere within those two minutes, the earth’s position in its yearlong orbit around the sun, triggered changes in daylength. The change from spring to summer appears seamless though the end of one season and the beginning of the next is measured to the nanosecond. Life on earth has evolved to respond to the predictable ebb and flow of daylength. Light sensitive receptors direct chemical changes within the body affecting behavior and development as seen most obviously in trees and plants.

The weeks before and after the arrival of summer hold the potential for producing magical moments of timeless beauty and peaceful retreat when nature takes a deep warm, relaxing breath and exhales.

A whisper of mist and gentle rain partner to dim the light, hide the sun, and erase all perception of time. The chill of spring and warmth of summer agree to mediation, making either imperceptible to detect. The wind’s contribution is so minimal, the moisture and misty curtain of fog offer more than enough resistance to silence all sound and movement. The only detectable motion is that of an isolated leaf rising from genuflection, after the weight of accumulated moisture forced it to bow to gravity.

On just such a day, when the world was huddled and dry and nature between breaths, I stowed my carbon fiber paddles, lightweight fishing rod into my Kevlar canoe, shouldered my pack and walked toward the river. The trail through the succession growth, transitioning from tilled crop field to woodlands, is hardly recognizable to a stranger despite years of use. Intentionally so, following a philosophy of, “leave no trace” my path roughly sought the shortest route, ever changing so slightly as shade and sun tolerant plants competed for dominance.

Passing first through a canopy of red oak branches, spawn of the giant that stood tall for a century, the thin bare oak branches performed a scratchy tune on the boat’s hull which magnified the uncomfortable sound to disturb the silence. Once in the open, tufts of amber grass, darkened by the rain to a rusty orange color, took advantage of a once mowed path to dominate as if marking the center of a road. Rose hips, escaped from the garden, and multiflora rose, spread their tentacles across the path, redirecting travel to avoid the curved thorns and torn clothes.

As the field grew, the occasional black walnut would tower above the spreading rose bushes, small red cedars, dried stalks of swamp milkweed and dogbane, to act as a lighthouse beacon marking the faint trail.

Breaking free onto the open flood plain, the river came into view. Isolated sections of its banks retained a few sentinel trees interspersed by a variety of brush and wild celery acted as a tattered tapestry revealing patches of flowing water.

The variety of trees and woody plants shared the same pale green color to suggest all were kindred spirits. In the distance looking down river, the fallow crop field allowed an unobstructed view beyond the bend in the river’s course, a quarter mile away. The green belt was notched at the bend by a tall American sycamore tree whose characteristic white trunk stood in sharp contrast as a neon landmark. Approaching the river at a breach in the eroded riverbank, I waded in and set the canoe on the still water below an island, which was once part of the pasture. The remains of tree stumps underwater, mid river, validated that the land was subject to the meandering river.

I set my pack behind the center seat and tied it to the slotted gunnel on a length of paracord. One bent shaft paddle was unstowed and leaned across the front thwart. Once aboard, I sat for a long moment to feel the gentle current, energized by gravity, magically carrying me downstream into summer. The sight and sound of the water’s surface, dappled by sparse raindrops surging from the falling mist, was meditative. I leaned forward, paddle across my lap, head pulled deep into my hood, I peered out of an imaginary cave, dry and comfortable, satisfied to move at the pace of the slow current on a journey from spring into summer.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author. Contact jjmish57@msn.com.

West Virginia v. EPA and Environmental Justice – our call to build community

A message from the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership Board

Last Thursday, on the final day of its 2021-2022 term, the U.S. Supreme Court released its decision in West Virginia v. EPA. The majority (6-3) opinion limits the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants under the Clean Air Act §111(d), and has dire environmental implications for our air, land, and waters. It is potentially devastating for Lower Raritan communities and landscapes already suffering the impacts of climate change, impacts which include more frequent storms that intensify flooding, increase pollution, enlarge underwater dead zones, and compromise quality of life for both humans and non-human species. The Court’s decision is an outrageous environmental injustice perpetuated on our communities of color and low-income communities, which have historically been forced to live in less-desirable low lying urban areas devoid of greenery, and are most vulnerable to rising temperatures and the extreme weather brought on by climate change. These populations will now be triply vulnerable due to the poisoning effects of poorly regulated greenhouse gas emissions.

While the Court’s ruling is devastating, it does leave room for the EPA to act on its duty to tackle carbon emissions from power plants, and the LRWP urges EPA to quick action on writing a new rule to cut carbon emissions. The Court’s rule of course does not affect our individual power to take action locally, for example by encouraging Governor Murphy to enact a moratorium on fossil fuel projects here in the Garden State, and by voicing opposition to local proposals for pipelines, fracked gas plants and other fossil fuel based power proposals (an especially ill-conceived plan is Competitive Power Ventures’ 630-megawatt power plant proposal for a densely populated Keasbey neighborhood already overburdened with fossil fuel pollutants). And the Court’s decision has no bearing whatsoever on how we build an informed, engaged community of environmental advocates and stewards working to confront a legacy of environmental injustices in our watershed and how we prepare our neighborhoods for a resilient future. We hope you will join the LRWP in this work through water quality monitoring, boat building, restoration, environmental education and more – see our events page for info.

6.30.2022 Raritan Pathogens Results

By LRWP Water Quality Outreach Coordinator Jocelyn Palomino

The Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County run a volunteer pathogens monitoring program from May to September every Summer. On Thursdays we collect water quality samples at 6 non-bathing public access beaches along the Raritan River, and report the results on Friday afternoons. This week, water quality tests show pathogens levels below EPA federal water quality standards all of our sites! Pathogens/Enterococci “colony forming units” (CFUs) are measured and used as indicators of the possible presence of disease-causing bacteria in recreational waters. Suitable levels for primary contact should not exceed 104 cfu/100mL. Although our results show pathogen levels under federal water quality standards for cleaner levels of water, please recreate on the river at your own risk and always be sure to wash your hands. Pathogens may pose health risks to people fishing and swimming in a water body. More information about our pathogens program is on our water quality monitoring webpage.

We’d also like to share a new map we’ve been working on to help improve the understanding of the water flow through the watershed. In the coming weeks, we will be integrating our bacteria findings into our new map. Special thanks to Brenda Allen for developing the map and providing this “sneak preview”.

Many thanks to the Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Middlesex County and Interstate

Environmental Commission for their partnership, and to our monitoring volunteers!

The Great Spring

by Brian T. Lynch, MSW

I know a forgotten place where some of New Jersey’s purest cool water springs from deep underground. And now it may be threatened.

This spring water generously flows from a small but verdant wetland along a streambed of glacial sand with barely a ripple. You won’t find this place on modern maps unless you know where to look. Its existence, however, was well known to Leni Lenape families who lived in the adjacent forests for perhaps thousands of years. They called this now forgotten place “great spring.” They called the stream “gentle flowing.”

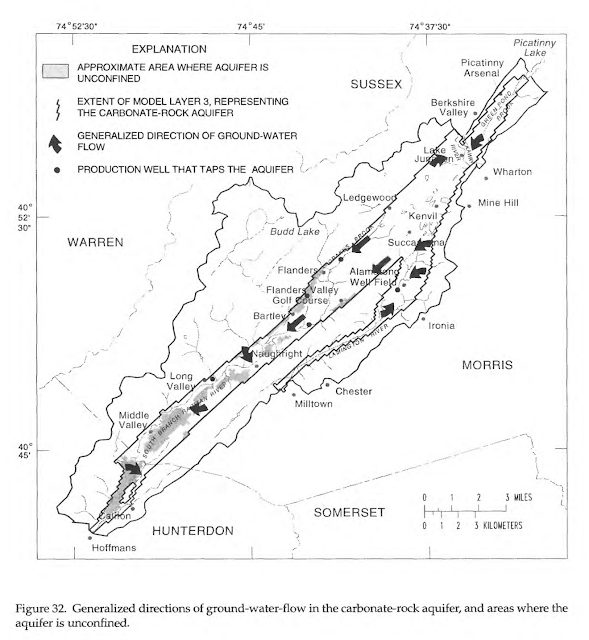

The Great Spring and its waters were also well known to the first European settlers in the Succasunna Valley. According to written accounts from the 1700s, folks marveled at the constant flow even during dry spells. The water was described as always cool and delicious. In what may have been a translation error back then, the early settlers called this stream the Black River. The actual Lenape name for this gentle flowing stream was “Alamatong” from which we get its modern name, the Lamington. While most everyone knows of the Black River or the Lamington River, the spring itself has faded from memory and disappeared from our maps. So, what the Native Americans knew, and most of us don’t, is that the Great Spring is literally the fountainhead of the North Branch of the Raritan River.

So where is this environmentally important spring? It is at the Southernmost edge of the former Hercules Powder property along U.S. Route 46 in Kenvil, New Jersey. You drove past it without notice if you ever traveled on Route 46 in Roxbury between Mine Hill and Ledgewood. Its outlet is literally across the highway from an IHOP Restaurant.

And why is the Great Spring a forgotten place? For over 150 years the spring has been an inconvenient appendage on 1,000 acres of privately owned industrial land where TNT and other explosives were manufactured. The spring’s wetlands have remained off-limits to the public and its ecology and geology have never been properly studied. A review of the New Jersey Highlands Environmental Inventory from 2013 suggests that the spring was not explicitly considered. And while everyone knows the former Hercules Powder property is a major pollution site, there is little public information on the extent of the contamination or the threats it may pose to the spring or the important aquifer below from which this water rises.

We do know that the now-abandoned Hercules property is laden with toxic chemical waste products from its bygone manufacturing days. We know there are acres of soil laced with PCBs, the by-product of burning chemical waste and other debris on-site. We know that the toxic chemicals used in the manufacturing of explosives still remain in some pipelines which run under buildings that haven’t been demolished yet. We know that some of these chemicals have contaminated the surrounding soil to an unknown extent and that these contaminants have migrated over the land and polluted surface waters in other places around the country where TNT was manufactured. Most of these sites, including several former Hercules plants in New York, New Jersey, California, and elsewhere, are designated superfund sites.

This Hercules property would qualify as a superfund site, but that was not the option the New Jersey DEP chose. In 2009, the Site Remediation Reform Act gave the DEP the power to allow private corporations to conduct all remedial activity on contaminated sites in New Jersey under the Department’s scrutiny. The State also created Licensed Site Remediation Professionals (LSRP) to assure the work is completed under DEP guidelines. Under this arrangement, Ashland Global Properties, who bought the Hercules tract after the company went out of business, hired the WSP Corporation to conduct the cleanup back in the 1970s. The work was begun but never completed. The LSRP responsible for the cleanup recently changed hands and a new company is now in charge of the work. Activity on the site is back underway.

In the decades since Hercules shut down, public awareness of the pollution on the site and progress in cleaning it up has faded. Few know that the underground aquifer and spring that surfaces on the Hercules site is the source of the Black River, an important link in the Raritan River system that provides drinking water for 1.8 million people. Numerous commercial well fields also tap this same aquifer to supply municipal drinking water to many towns in the region.

1996 U.S. Geological Survey Water Resources Investigation Report

This juxtaposition of the Great Spring wetlands, a precious natural resource, and the massively contaminated Hercules site, a commercially valuable property, is bound to create competing interests. Roxbury Township officials would like this site safety cleaned up. They are understandably eager to restore the site for future development. This is the largest undeveloped land left in Morris County and it is close to major rail and highway transportation hubs. Environmentalists would love to see the wetlands and surrounding rainwater recharge areas on the property protected and preserved.

Since November of 2021, the remediation process accelerated under a new corporation and the new LSRP. The Roxbury Planning Board approved two work permits, and earth moving equipment is on-site taking down trees, removing PCB contaminated soil, and bringing in clean fill to replace it. A bioremediation staging area is being built where other chemically contaminated soil will be brought and be microbially composted. The soil will be held in six large “pods” and seeded with a bacterium that breaks down the chemical components of TNT. The process is expected to take about six years.

A map showing the location of the soil remediation pods was presented at a public meeting in Roxbury last November. Of the more than 800 acres of land on which these bioremediation pods could be located, the map appears to show the staging area directly beside the Great Spring wetlands. The rationale for this decision or any mention of the spring was apparently not discussed at the meeting.

Local environmentalists and freshwater advocacy groups familiar with the Hercules tract are anxious to learn more. If chemical toxins on this site leach into the surface water at the spring or seep into the aquifer below, the water supply for 1.8 million people could be in jeopardy. Recent activity on the site has come to the attention of the Raritan Headwaters Association (RHA), which monitors water quality within the upper Raritan River watershed. RHA has begun collecting information to independently assess environmental concerns. The lack of public information about cleanup operations and the low level of public awareness about the threat to water supplies is a worrisome combination.

(4/17/22 Addendum)

The Question: The Great Spring contributes 2.2 billion gallons* of water a year to the Raritan River, which in turn serves the water needs of 1.8 million people downstream. The presence of toxic soil on the same land from which flows the Black River begs the question: Is it wise to bring the most contaminated soil on the property to a bioremediation site at the edge of this spring?