The Great Spring

by Brian T. Lynch, MSW

I know a forgotten place where some of New Jersey’s purest cool water springs from deep underground. And now it may be threatened.

This spring water generously flows from a small but verdant wetland along a streambed of glacial sand with barely a ripple. You won’t find this place on modern maps unless you know where to look. Its existence, however, was well known to Leni Lenape families who lived in the adjacent forests for perhaps thousands of years. They called this now forgotten place “great spring.” They called the stream “gentle flowing.”

The Great Spring and its waters were also well known to the first European settlers in the Succasunna Valley. According to written accounts from the 1700s, folks marveled at the constant flow even during dry spells. The water was described as always cool and delicious. In what may have been a translation error back then, the early settlers called this stream the Black River. The actual Lenape name for this gentle flowing stream was “Alamatong” from which we get its modern name, the Lamington. While most everyone knows of the Black River or the Lamington River, the spring itself has faded from memory and disappeared from our maps. So, what the Native Americans knew, and most of us don’t, is that the Great Spring is literally the fountainhead of the North Branch of the Raritan River.

So where is this environmentally important spring? It is at the Southernmost edge of the former Hercules Powder property along U.S. Route 46 in Kenvil, New Jersey. You drove past it without notice if you ever traveled on Route 46 in Roxbury between Mine Hill and Ledgewood. Its outlet is literally across the highway from an IHOP Restaurant.

And why is the Great Spring a forgotten place? For over 150 years the spring has been an inconvenient appendage on 1,000 acres of privately owned industrial land where TNT and other explosives were manufactured. The spring’s wetlands have remained off-limits to the public and its ecology and geology have never been properly studied. A review of the New Jersey Highlands Environmental Inventory from 2013 suggests that the spring was not explicitly considered. And while everyone knows the former Hercules Powder property is a major pollution site, there is little public information on the extent of the contamination or the threats it may pose to the spring or the important aquifer below from which this water rises.

We do know that the now-abandoned Hercules property is laden with toxic chemical waste products from its bygone manufacturing days. We know there are acres of soil laced with PCBs, the by-product of burning chemical waste and other debris on-site. We know that the toxic chemicals used in the manufacturing of explosives still remain in some pipelines which run under buildings that haven’t been demolished yet. We know that some of these chemicals have contaminated the surrounding soil to an unknown extent and that these contaminants have migrated over the land and polluted surface waters in other places around the country where TNT was manufactured. Most of these sites, including several former Hercules plants in New York, New Jersey, California, and elsewhere, are designated superfund sites.

This Hercules property would qualify as a superfund site, but that was not the option the New Jersey DEP chose. In 2009, the Site Remediation Reform Act gave the DEP the power to allow private corporations to conduct all remedial activity on contaminated sites in New Jersey under the Department’s scrutiny. The State also created Licensed Site Remediation Professionals (LSRP) to assure the work is completed under DEP guidelines. Under this arrangement, Ashland Global Properties, who bought the Hercules tract after the company went out of business, hired the WSP Corporation to conduct the cleanup back in the 1970s. The work was begun but never completed. The LSRP responsible for the cleanup recently changed hands and a new company is now in charge of the work. Activity on the site is back underway.

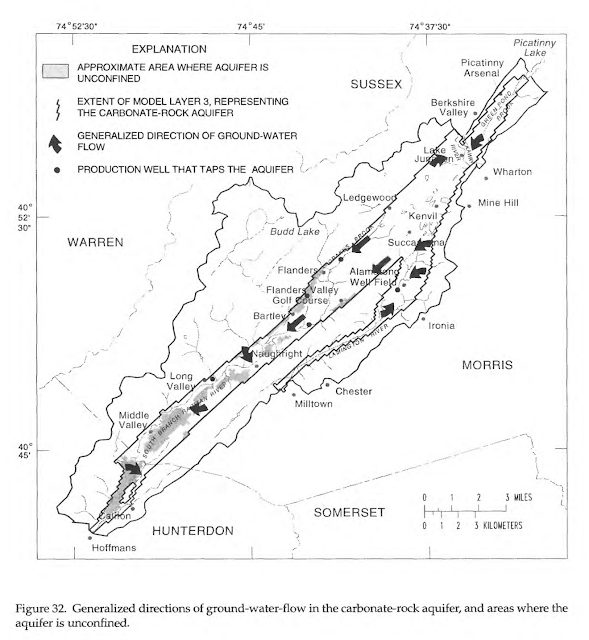

In the decades since Hercules shut down, public awareness of the pollution on the site and progress in cleaning it up has faded. Few know that the underground aquifer and spring that surfaces on the Hercules site is the source of the Black River, an important link in the Raritan River system that provides drinking water for 1.8 million people. Numerous commercial well fields also tap this same aquifer to supply municipal drinking water to many towns in the region.

1996 U.S. Geological Survey Water Resources Investigation Report

This juxtaposition of the Great Spring wetlands, a precious natural resource, and the massively contaminated Hercules site, a commercially valuable property, is bound to create competing interests. Roxbury Township officials would like this site safety cleaned up. They are understandably eager to restore the site for future development. This is the largest undeveloped land left in Morris County and it is close to major rail and highway transportation hubs. Environmentalists would love to see the wetlands and surrounding rainwater recharge areas on the property protected and preserved.

Since November of 2021, the remediation process accelerated under a new corporation and the new LSRP. The Roxbury Planning Board approved two work permits, and earth moving equipment is on-site taking down trees, removing PCB contaminated soil, and bringing in clean fill to replace it. A bioremediation staging area is being built where other chemically contaminated soil will be brought and be microbially composted. The soil will be held in six large “pods” and seeded with a bacterium that breaks down the chemical components of TNT. The process is expected to take about six years.

A map showing the location of the soil remediation pods was presented at a public meeting in Roxbury last November. Of the more than 800 acres of land on which these bioremediation pods could be located, the map appears to show the staging area directly beside the Great Spring wetlands. The rationale for this decision or any mention of the spring was apparently not discussed at the meeting.

Local environmentalists and freshwater advocacy groups familiar with the Hercules tract are anxious to learn more. If chemical toxins on this site leach into the surface water at the spring or seep into the aquifer below, the water supply for 1.8 million people could be in jeopardy. Recent activity on the site has come to the attention of the Raritan Headwaters Association (RHA), which monitors water quality within the upper Raritan River watershed. RHA has begun collecting information to independently assess environmental concerns. The lack of public information about cleanup operations and the low level of public awareness about the threat to water supplies is a worrisome combination.

(4/17/22 Addendum)

The Question: The Great Spring contributes 2.2 billion gallons* of water a year to the Raritan River, which in turn serves the water needs of 1.8 million people downstream. The presence of toxic soil on the same land from which flows the Black River begs the question: Is it wise to bring the most contaminated soil on the property to a bioremediation site at the edge of this spring?