Thin Blue Lines

Article by Joe Mish. Aerial images taken on flight provided by Lighthawk compliments of No Water No Life

If all the water that ever flowed from the Raritan river drainage could be measured, its contribution to the depth of the ocean would be impressive. Think of that watershed as a collection agency for the world’s oceans.

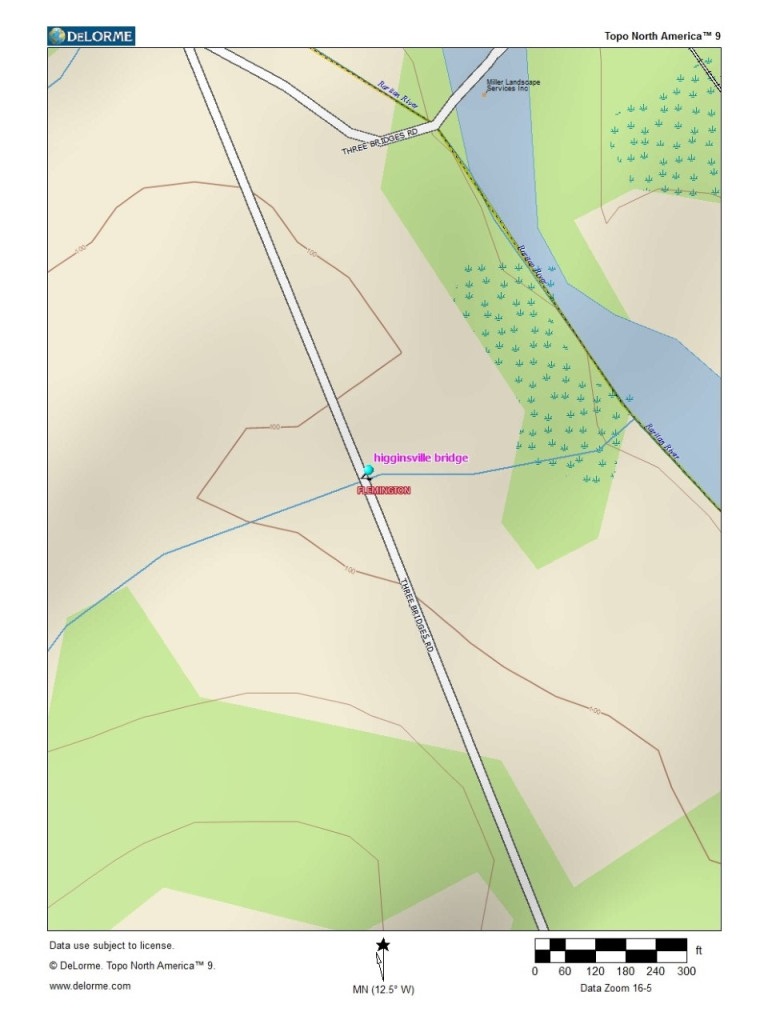

An aerial view of the Raritan River clearly shows its two main branches, the South Branch and the North Branch. From the perspective of the confluence, its two main branches get their name, despite both arising north of their meeting place. The confluence marks the beginning of the Raritan River.

A closer look reveals the larger tributaries which feed the main branches; Rockaway creek, Black river/Lamington River and the Neshanic River, all of which are clearly noted on maps.

No less important are the numerous smaller brooks and creeks whose contributions are significant and whose names may appear only on old maps or engraved on marble plaques set in structures that bridge their banks. Peter’s brook, Chambers brook, Pleasant Run, Prescott Brook, Assicong Creek, Minneakoning Creek, Holland Brook and the First, Second and Third Neshanic Rivers, are identified on some maps though only Holland Brook has one sign along its nine mile winding course. Hoopstick and Bushkill are lesser known streams, within plain view, that bear no identifying signage and are often represented as nameless blue lines.

There are dozens more minor streams whose names appear nowhere except in obscure archives. Each one eventually feeds not the Raritan or its two main branches above the confluence. Knowing someone’s name is a sign of respect.

Calling someone by the wrong name can be embarrassing. However, the signs that misidentify the North Branch of the Raritan River as the Raritan River proper, have failed to embarrass those responsible for posting such signs.

Many smaller seeps and springs whose names have been lost to the ages add to the accumulated flow. Driving along the Lamington River for instance, there are endless watery traces arising from springs within the woods that empty into larger tributaries. Many are just moist creases worn through the soil over time, which collect rainwater and snowmelt to supplement the downstream daily flow.

Maps show endless springs, which make the cartographers final draft as thin blue lines. Often a network of converging shorter lines, each with a defined beginning, join to form larger streams like Pleasant Run and Holland brook.

Obscure water sources fascinate me simply because their anonymity and remote locations arouse my curiosity about the natural communities that might exist in such rarely visited places. Their presence represents a convergence of habitat types that attract birds and wildlife. Though they bear no labels to honor their faithful contribution to the next blue line and ultimate confluence, their importance must not be overlooked.

Many springs which appeared on old maps, no longer exist, eliminated by construction of sewer lines or otherwise diverted or filled in. As maps are revised and generations fade, these streams exist only in a cartographer’s archive.

My appreciation for these disappearing thin blue lines was heightened when I recently discovered that as a kid I walked over Slingtail brook every day on the way to school. At some point this little stream which bore a name, was diverted through a sewer line under the pavement. More amazing, even older residents had no memory of that stream, its presence and name lost to the ages. I did find a reference to Slingtail Brook in the Woodbridge, New Jersey newspaper archives dated 1939. The property through which a portion of the stream flowed was up for sale. A clause by the seller stipulated the brook not be diverted or covered over.

“Conveyance will be made subject to the following condition: That the course of Slingtail Brook as now existent, be not changed or diverted from its course or that said stream and flow of water therein be not blockaded, dammed or otherwise restricted.

Take further notice that the Township ………… “

Fords Beacon, May 12, 1939”

Somewhere in time the requirement that Slingtail remain unmolested, was lost to progress and legal wrangling. Such is the fate of so many smaller streams, especially when their names only exist in oral history and no signage marks there presence.

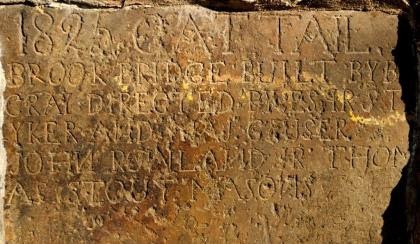

One small trickle of a stream that has miraculously retained its nature and name, is Cattail Brook.

Cattail brook arises from a convergence of network of bubbling springs, supplemented by runoff from rain and snowfall. It begins as hardly more than a trickle, directed by gravity, from the south facing ridge of the heavily wooded Sourland Mountains, near East Amwell, NJ. Cattail brook gives birth to Rock Brook, a tumultuous and moody stream that joins the more sedate Bedens Brook on its way to the Millstone River. The Millstone joins with the Raritan River to make its final contribution to the earth’s deep blue oceans.

An extended winter freeze, preserving snow from a previous storm beyond its expected stay, was interrupted by a thaw and heavy rain. The melting snow joined the torrential downpour as it flowed over frozen ground to collect in every shallow crease leading to the river. The water’s velocity was enhanced by the decreasing gradient of deep well worn pathways etched into the earth.

The banks of successfully larger streams barely contained the accumulation of water delivered from the network of anonymous thin blue lines. Acting as a single entity, the collection agency, if you will, of the Raritan River drainage, faithfully delivered its contribution of sweet water to the world’s salty oceans.

The Raritan River becomes the Raritan Bay downstream of the New Jersey Garden State Parkway Bridge. With a poetic flourish, the salt water bay and lower Raritan River are stained blue, saturated with the blue ink used to represent the thousands of nameless pale blue lines drawn on maps of the extensive Raritan River watershed.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Contact jjmish57@msn.com. See more articles and photos at winterbearrising.wordpress.com.