Article and photos by Joe Mish

A hummingbird and orange trumpet flower engage in an evolutionary dance of equal partnership that has lasted for eons. The flower not only took advantage of an array of pollinators but also stole the heart of man who would seek to propagate flowers far beyond their natural range and ability to survive.

A name logically follows the existence of an idea, a person, place or a thing and forever provides an instant reference, complete with assigned identifiable characteristics. So before there was a month named May, a segment of time existed in nature where birth and bloom dominated the season.

The mythology from which the name of May arose was based on the same natural observations seen today. Stories of the stars and the gods became the reference points displayed on the night sky overhead projector to help explain observed phenomenon. The poetic phrase, “April showers bring May flowers” provides information sufficient enough for most people to understand the season. Instead of placing flowers at the altar of the goddess Maia we now send flowers to our mothers on a day designated to show her our appreciation, same story, different day.

Going back to the time before May, can you imagine discovering the first flower ever to bloom? In retrospect it would have meant that some plant had evolved to take advantage of a new method of pollination that relied on insects rather than wind. At the time of discovery, however, the moment had to be absolutely magical. Here was something so different in structure, color, scent and profusion that it instantly intensified a fledgling human emotion that speaks to the appreciation of beauty. The flower not only took advantage of insect pollinators but at that moment stole the heart of man who would later seek to propagate flowers far beyond their natural range and ability to survive.

Watching a rambunctious fox pup at a distance, I saw what appeared to be orange pollen on its solid black nose. As the pup was playing around the daylilies I imagined he stuck his nose inside a funnel shaped orange flower, designed for bees and hummingbirds, to come away with the telltale signs of brightly colored pollen grains. If he sniffed a few more flowers he actually became the “bee” and a willing, if not random, participant in asexual reproduction. The part that serendipity plays in nature and science can never be underestimated and its potential never unappreciated when unprecedented success results.

Fox pups are not the only pollinators unknowingly pressed into service by the ingenious evolutionary design of flowers. It is a laugh riot, for some reason, to see a dusting of yellow or orange pollen on the nose of a child or adult who sniffs a flower in pursuit of its scent. Eyes closed, as if about to plant a kiss, the human pollinator presses forward until nose touches stamen.

The entire event, so instinctive and innocently conducted, that the “bee” comes away unaware of its role in the evolutionary drama of species reproduction and survival. A kind friend will of course bring attention to the dusting of pollen left by such an intimate encounter and be trusted to address it discreetly.

Bees of all kind have ‘pollen baskets’ on their back legs which hold an accumulation of pollen grains that appear as large colorful round beads on opposite back legs. Watch one of those big furry yellow and black bees and you can easily see the lumps of colorful pollen that varies from flower to flower.

Paddling along the south branch, wild columbine can now be seen in select places on north and west facing red shale cliffs. These delicate plants grow from roots wedged between the layered red shale well above the surface of the water. The reddish pink tubular flowers with a common yellow center resemble a group of ice cream cones joined to form a common opening which leads to several individual tails. This structure encourages contact with the centrally located pollen that has to be brushed against in order to reach several sources of nectar located in each tail. This flower must have had a hummingbird sitting on the design team who decided not only the flowers structure but the time the flower was set to bloom. Hummers arriving in early spring from Mexico and Central America have a ready source of food to replenish the energy spent in their annual migration north.

Consider the greatest mayflower of all and the part it played in another notable migration. The “Mayflower”, was a ship that sailed to our shores bearing its human pollen to establish new life on the North American continent The ship, so named by unknown whimsy and intended as a supply barge, grew to evolve much as early flowers did into an effective delivery system directed by nothing more than chance. Like a flower it bloomed, spread its pollen and ‘died back’ soon after returning to England.

May apples, Virginia bluebells, trout lilies, trillium, jack-in-the pulpits and spring beauties are a small sample of local May flowers that represent the spectrum of a floral legacy whose genealogy traces back to the earliest flowers. Consider that flowers are living things that in some magical way recruited man to further their propagation in exchange for a glimpse of eternal beauty, dreams and imagination to expand the universe of human potential with unbounded creativity and expression.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

A red eyed vireo briefly descends from the treetops to provide a fleeting glimpse of one of the most common, yet rarely seen birds, east of the Mississippi.

March is the last piece of evidence needed to prove winter has gone by. No matter the weather March brings, her legacy of cold and snow, as the step child of winter, is invalidated by “the first day of spring” conspicuously stamped twenty-one days into the month on just about every calendar printed.

Further visual proof needed to allay the fear that winter is here to stay, are the strands of migratory birds that precede peak migration in the next couple of months. Perfectly positioned between two rivers that lead to the sea and link to the main Atlantic flyway, Branchburg comes alive with colorful winged migrants. Some birds are just passing through while others stay to establish breeding territories.

You don’t really need to be a graduate ornithologist with the ability to differentiate a magnolia warbler from a black throated warbler to enjoy all the feathered gems that pass our way in spring.

During a recent snowfall the view of several brilliant red, resident cardinals, dodging among the tight branches of a nearby holly tree resplendent in dark green leaves and an overabundance of red berries was a sight to behold. The gently falling snow turned the scene into a living Christmas card.

Bird seed scattered on the ground immediately near the back glass sliding door was being appreciated by a flock of brave juncos. The scene was calm and predictable with an occasional song sparrow darting across the stage. Suddenly, standing on the ground next to the glass was what appeared to be a Parula warbler. I ran for the camera to no avail as the little bird disappeared quicker than a shooting star. It didn’t seem plausible that a warbler would be in this area so early but there it was. Looking through the, ‘guide to field identification, Birds of North America’, I reviewed the dazzling array of warblers each differentiated by plumage unique to adult and juvenile, male and female with a cautionary note on hybrid warblers and seasonal plumage. I guess it was a male Parula warbler.

The conflict of identification versus the excitement at seeing a strange colorful bird lingered for a moment until I realized it was the sight of the bird that provided the magic.

Knowledge of the scientific classification was irrelevant to the enjoyment of simply noticing something that appeared to be different and gave pause to a moment of thoughtfulness or beauty.

As an example, you might gaze upon a stunning portrait of another person or a dreamy sunset and immediately be drawn in even though you have no idea of the person’s name or the location of the sunset.

Beauty is its own reward and needs no further qualification.

Birds are creatures which reflect the colors that dripped from God’s palette of infinite hues used to paint the portrait of life. One could argue ‘colors’ have wings to spread nature’s beauty far and wide and taken together they are called, ‘birds’.

Soon the area will be crowded with migrating birds, the most colorful of which are the warblers. A walk along the river flyways while scanning the treetops will reveal small flocks of birds that look like no other you have ever seen. The bright plumed breeding males will be the first to arrive as they travel in the safety of numbers. It is hard to imagine that these diminutive delicate appearing birds migrate yearly to Central America, Mexico and the West Indies from New Jersey and points north. After arriving in breeding areas, the males separate to set up mating territories defended by trilling songs sung loud and often.

The colorful and numerous male warblers representing several species are spectacular to observe in their diversity of color swatches, masks, vests, necklaces and caps. Each color pattern represents a different species despite similar size and intermingling of flocks.

Even the most ‘nature oblivious’ and ‘nature neutral’ observers may have their heads compulsively turned by the accidental appearance of a flash of tropical color among the local treetops.

Perhaps a seed of curiosity may be sown, nurtured and cultivated from a brief encounter with a spring warbler. That dangling thread of gangly curiosity left by a Magnolia warbler or Yellowthroat can easily draw the observer into the world of nature to wander and wonder at the infinite complexities that bind all living things. To believe beauty is only skin deep and fleeting is to ignore the power, depth and satisfaction the beauty of nature has to offer. Asking nothing in return, not even requiring that you can differentiate a Rufous sided towhee from a Cape May warbler, beauty exists only to be appreciated.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Eager and hungry fox pups survived the mercurial spring floods to feed voraciously on mom in the bright sunlight of a late April morning.

April is the quintessential month of spring, the first month to start with a vowel after a bleak winter of hard consonant constructed months. The name April is probably derived from the Latin infinitive, aperere, ‘to open’, but that consideration is at the risk of offending the claims of the goddess of love, Aphrodite, and Apollo the son of Zeus, their namesake month.

I see April as a grand series of ever changing dance steps performed in tune to the great celestial choreography of the planets and stars. One planetary misstep and the world comes crashing down. It is, however, a play without flaw that brings the predictability of the seasons and the impish April to improvise her set of daily surprises that precede the full bloom of May.

April is a charming minx with dancing green eyes whose mercurial ways give false hope to early gardeners as she whirls in the white robes of a sudden snow squall. Days of bright sunshine are mixed with bone chilling moist air, frosts and gentle rain or hailstorms of biblical proportion. These are the veils April sheds as she improvises dance steps to tease and mislead, all the while faithfully delivering the solemn promise of May.

Edwin Way Teale, a noted author and naturalist claims that, “spring approaches from the south at fifteen miles a day”. If you were to drive from New Jersey to Maine in mid April, you could actually see spring approach.

Travelling north, you go back in time to see spring begin.

As you drive through New Jersey, forsythia planted along road medians would be in full yellow bloom as tree buds give birth to pale green leaves.

The crowns of naturalized red maple dominated hardwoods would have shed their maroon veil to now wear a haze of light green unfurling leaves that will continue to darken as they mature

Oak dominated hillsides and lowlands scattered with black gum, hard maple, beech, ash and sycamore appear as colorful as autumn with interlacing crowns covered in non reflective red, yellow, pink and salmon hued emerging leaves.

The color and blooms slowly fade as you travel north. The further you travel in one day, the more the landscape appears as if drawn on individual sheets of paper flicked by hand to appear as if moving. The individual frames of the ‘movie’ become alive and reveal the living, leading edge of the manifestations of spring.

The return journey south allows you to enjoy the second coming of spring and the insight that comes with a second chance.

Along the South Branch, a Great Horned Owl has been nurturing a clutch of eggs that will produce at least one full sized, flightless owlet to stand constantly alert for parental food deliveries in mid April.

During two trips down the South Branch in February and March, a female red fox ran along the river bank to expose herself as if to draw me away from her riverside den. She would run along the bare vertical bank then walk out onto a gravel bar, sit down and watch me approach. When I got too close she would run off and wait further downstream. At one point she ran across a sand bar that was flanked by a pair of mallards standing on the bare ground and a great blue heron posed in foot deep water. All three birds stood perfectly still as the fox ran between them. Neither the ducks nor the heron made any move to escape as if they knew the fox was not a threat that day.

I can only hope the fox waited until April to have her pups in light of the flood that came in late March. Perhaps April will reveal a gentle rain that favors the survival of not only the fox pups, but the bank swallows, flycatchers, muskrat and turkeys that might have dens or nests close to the riverbank and flood plain.

It is amazing how migration, breeding, births and nurturing coincide with seasonal events as if truly participating in a dance whose every step is critical to survival.

We have evolved physiologically to fit into a small, ‘temporary’ niche circling in an eddy on the river of change. If the changes take place faster than we can evolve, we go away.

Despite the vagaries of April’s whim, she shows the world an emergence of life that has learned her fickle ways and dances in step to lovingly embrace such a wild partner.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

The sea run shad, striped bass and herring that gather at the mouth of the Raritan River attract animals high on the food chain such as this harbor seal. Whales and dolphin have also been sighted over the last few years not in small part from the contribution of the Raritan River and its sweet water branches.

The spring-fed north and south branches of the Raritan River join in a marriage of sweet water at their confluence, on an endless journey to the sea. Each hidden spring and brook along the way, contributes its own genetic identity, mixed in a final blend at the mouth of the Raritan River.

Where the fresh water meets the salty sea, the ebb and flow of tides stir the brine into fresh water to create a stable buffer zone of brackish water.

These back bays and estuaries formed at the mouths of rivers are a perfect place for young of the year striped bass to gain in size before going offshore to migrate. American, hickory, gizzard shad, river herring, such as blueback herring and alewives also gather here and search for ancient breeding grounds located far upriver.

In the time before dams, sea run fish migrated far upstream into the north and south branch. Fishing was a robust industry in early colonial times where the seasonal migration of herring and shad was a profitable business.

The construction of dams to power mills along the river put a halt to upstream commercial fishing. The mills and dams were not welcomed by colonists who made a living from the seasonal fisheries. One account tells of early settlers in the mid 1700s, unhappy with a mill dam just below Bound Brook, making nightly raids to dismantle the dam and allow shad to continue their upstream migration.

Fast forward to today, the river still flows to the sea and the shad and herring gather to swim upstream.

In 1985 pregnant shad from the Delaware River were transplanted to the South Branch as part of a program to restore a shad migration along with planned dam removals.

Dams that have blocked migrating fish have recently been removed. The Calco dam near the former Calco Chemical Company built around 1938, cleared the way for migrating fish to reach the confluence of the Millstone and Raritan where a flood control dam was built. Known as the Island Farm weir, completed in 1995, it includes a viewing window and fish ladder to allow the dam to be bypassed by fish travelling upstream.

As part of the shad restoration project, volunteers working with Rutgers scientists tag shad and herring in an ongoing effort to gauge the success of the fish ladder and restoration efforts. Preliminary findings can be accessed at, http://raritan.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NJDEP-2013-American-shad-restoration-in-the-raritan-river.pdf

A live underwater camera is placed at the dam each year after threat of ice has past. The camera is now operated by Rutgers University and may be seen online at http://raritanfishcam.weebly.com/fish-guide.html and at http://raritan.rutgers.edu/resources/fish-cam/

Aside from the Calco dam, three of five dams upstream of the Island Farm Weir, two dams on the Raritan, the Nevius street and Robert street dam and one on the Millstone have been removed. All in anticipation that the head dam at Dukes Island Park and the low dam at Rockafellows Mills on the South Branch will eventually be deconstructed.

See the above link for the video of the Nevius street dam removal. Go to MENU, open videos/multimedia to see Nevius street dam deconstructed.

See this link for a look at the Duke’s Island dam today; https://vimeo.com/259404286

The dream to restore our rivers and fisheries to their unmolested glory is well on the way to reality. Bald eagles now nest along the Raritan and its branches, soon to be joined by spawning shad and herring.

The vision of a pristine river valley, interrupted by 300 years of abuse and neglect is slowly emerging from the river mist as a magical apparition. The magic supplied by the hard work of Rutgers scientists and dedicated volunteers who echo the words of Rutgers president Thomas, who served in 1930, “Save the Raritan”.

As an aside to this article, I will share a sobering and emotional experience involving the Island Weir Dam that took place in 1995. The intent is to emphasize the importance of safety while paddling in general and especially when near dams or in cold water.

See page three of this link for a description of what happened that day: http://www.wrightwater.com/assets/25-public-safety-at-low-head-dams.pdf

I was paddling on the Delaware and Raritan Canal which parallels the Millstone River about two miles from where the dam is located at the confluence of the Millstone and Raritan rivers. This was a training session for a cold water canoe race that takes place each April in Maine. I am an experienced paddler, familiar with cold water immersion and so was wearing a wet suit with a dry top and pants along with a life jacket/pfd while on the calm water in the canal.

As I neared the end of my trip at the Manville causeway, several police cars slowly drove by and turned around as if searching for something. Sirens were wailing and more police and rescue vehicles were seen and the road blocked off. First thought was the body of a woman who was reported to have ended her life in the Millstone a week before was found.

As it turned out a kayaker and two companions in a canoe decided to run the dam. According to my recollection of the news article; the canoe made it through first, while the kayaker who followed, failed to clear the dam and was stuck in the hydraulic.

According to the news article, ‘the experienced paddlers’ wore no thermal protection or pfds when they ran the dangerous dam. It was reported that the canoers paddled back to help their companion and they capsized in the hydraulic. Once you cross that line which marks the downstream flow from the water cycling upstream, you will be pulled into the hydraulic.

The kayaker and one of the men in the canoe were washed out of the turbulent water but the other was lost, his body never recovered.

A hydraulic occurs when the weight of falling water creates a hole which is then filled by downstream water being pulled upstream in an endless re-circulating current parallel to the dam. Low head dams may be altered to prevent or mitigate a hydraulic.

There is a point of no return where you can actually see a line that separates the water flowing downstream from the water flowing back upstream to power the hydraulic.

Island Weir Dam at the confluence of the millstone and Raritan River. You can see the horizontal shelves that are the fish ladder in the center and the subsequent stepped redesign to mitigate the dangerous hydraulic.

There have been several more drownings involving dams on the Raritan and its branches. I recall another at the Headgate, which is the dam created by the Duke estate below the confluence of the North and South branches. The paddler went over and was lost in the hydraulic below.

This is the headgate dam at Dukes Island Park. Created to collect river water via the Dukes canal to power the estates and supply water to the series of ponds built at decreasing elevations to allow the water to return to the river by gravity.

No warning signs are posted to alert paddlers to the danger ahead. On the downstream face of the dam is a warning to keep off.

Too little too late warning.

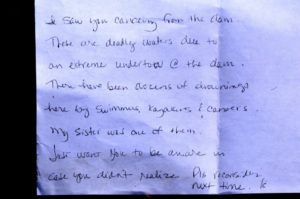

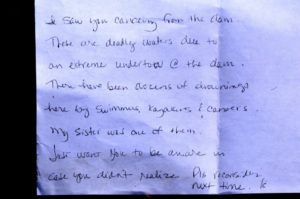

Paddling on the South Branch from Rockafellow’s mill rd, just below the low head dam that forms Red Rock Lake, this note was placed on my windshield. Though I was no where near the dam, contrary to what the note states, the message was at once heart breaking and shown here, now serves as a warning to all; beware of the dangers of low head dams.

This sign is placed about 5 football fields above the dam at red rock lake on the South Branch. It’s placement a puzzlement that mitigates its message.

Dam at Red Rock Lake.

Though rivers like the South Branch and North Branch are reputed to be no more dangerous than a swimming pool, tragedy can strike when least expected. Strainers, trees that fall into the river blocking passage, can snag and capsize a boat and entangle the paddler in its branches under pressure of a fast current. Low head dams can drown a paddler by immersion or entanglement on debris as the paddler is unable to wash out of the turbulent recycling water. Search on line to get an idea of how widespread is the danger of obscure low head dams and loss of life across the country.

Paddling when river temperatures are well below normal body temperature requires thermal protection no matter the air temperature. Wearing a pfd alone will not be enough to survive if your body temperature drops before you can be rescued or self rescue. Such was the case of a paddler on Round Valley reservoir a few years ago.

Typically water temp during the winter and early spring on the South Branch is 41 degrees. More than enough to cause a spasm to block your ability to breathe even before hypothermia sets in. See this link for a detailed explanation of the effects of cold water immersion. Remember, ‘cold water’ does not have to be that cold.

http://www.coldwatersafety.org/ColdShock.html

Overturning in fast water, a boat can instantly fill with a hundred gallons of water. Each gallon weighing 8 pounds, can pin or crush a paddler between the canoe and any obstruction. Such was the case on a locally sponsored canoe trip in shallow water on a beautiful day on the South Branch. One paddler was trapped under the canoe in a strainer. Eventually he popped out from under the boat, shaken but safe. The canoe was stuck fast in the strainer, filled with hundreds of pounds of water. Never be downstream of a capsized canoe.

Tragedy can occur on the calmest day under brilliant blue skies, always wear a pfd and be alert to potential dangers, especially dams.

Low head dam across the North Branch just above rt 202 makes a difficult passage during low water portage and a dangerous hydraulic during high water.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Canada Geese in a snowstorm on the South Branch appear at ease as the falling snow softens the scene.

Canada Geese in a snowstorm on the South Branch appear at ease as the falling snow softens the scene.

The January blizzard raged, turning the darkness into an opaque curtain of white. Almost a foot of powdered snow covered the ground before midnight.

The broadcast news reported that NJ had declared a state of emergency shutting down roadways throughout the state. The setting was just right for the midwinter parade on the South Branch. Thousands attended and the main thoroughfare was jammed with local residents and visitors. As I stepped outside to get a head start on clearing the driveway, the sound of geese, thousands of geese, overpowered the drone of the wind driven snow. So impressive was the magnitude of the unalarmed chatter, I was compelled to investigate. Alerting my family where to search for the body, I headed into the storm.

The closer I got to the river the louder and more beckoning the sound became. Moving slowly through the trees toward the river bank, the din from the geese on the open water was deafening. The river was filled wall to wall with migrant and resident Canada geese. Some started to get up and fly. Others just drifted by. All appeared as black silhouettes against the snow and reflective water. Thousands upon thousands all in chorus, the rhythm and sound of their calls rose and fell as if one voice. Occasionally all sound would hesitate into a moment of absolute silence. The silence was as dramatic as the din.

Animals generally become fearless in extreme weather and at the height of this snowstorm the geese collectively tolerated my close approach.

As I closed in, the birds parted, momentarily leaving a void of reflective water. The surface was again soon covered with geese as the specter of an interloper was confidently dismissed.

The Geese were packed so tight; they appeared as if in a big cauldron that was being stirred. One group was drifting down with the current while the other was going back up stream in a re-circulating eddy below the island.

Aside from the geese, the river was filled with joined platelets of gray and white ice, strong enough to support several of the large birds. A display of motionless geese rode atop drifting ice flows, escorted by a cadre of even more geese floating alongside, all travelling at the same speed.

This looked all so familiar. Suddenly it struck me. I could have been watching a fourth of July parade with themed floats and accompanying marchers. Certainly the band was playing a familiar tune as spectator geese lined the banks and joined in the chorus.

How odd that here was a gathering of what seemed to be all the geese in New Jersey having their own parade. As if to celebrate some event sacred to the hearts of all geese, each bird taking comfort in knowing they owned the night and there would be no human eyes to witness their ethereal rite.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joseph Mish

A thin blue line drawn on a map, comes to life in this photograph. A plaque, inset in a concrete bridge spanning the stream, constructed in 1923, a map showing a thin blue line depicting the stream and an image of the stream as it exists today just before it reaches the South Branch.

If all the water that ever flowed from the Raritan River drainage could be measured, its contribution to the depth of the ocean would be impressive. Think of that watershed as a collection agency for world’s oceans.

An aerial view of the Raritan River clearly shows its two main branches, the South Branch, and the North Branch. The South Branch draining more area than the North. The confluence of the North and South branch mark the beginning of the Raritan River.

A closer look reveals the larger tributaries which feed the main branches; Rockaway creek, Black River/ Lamington River and the Neshanic River, all of which are clearly noted on maps.

No less important, are the numerous smaller brooks and creeks whose contribution is significant and whose names may appear only on old maps or engraved on marble plaques set in the structures that bridge their banks; Peter’s brook, Chamber’s brook, Pleasant run, Prescott brook, Assiscong creek, Minneakoning creek, Holland brook and the First, Second and Third Neshanic rivers. Hoopstick, Prescott and Bushkill are lesser known streams, within plain view, that bear no identifying name.

There are dozens more minor streams whose names appear nowhere except on an obscure online list. Each one eventually feeds into the Raritan or its two main branches above their confluence. Knowing someone’s name is a sign of respect. Calling someone by the wrong name can be embarrassing. However, the sign that identifies the North branch of the Raritan as the Raritan River proper, has failed to embarrass those responsible for posting such signs.

Many smaller seeps and springs whose names have been lost to the ages, add to the accumulated flow. Driving along the Lamington, for instance, there are endless watery traces, arising from springs within the woods that empty into larger tributaries. Many are just moist creases worn through the soil over time, which collect rainwater and snow melt to supplement the downstream daily flow.

Maps show nameless springs, which make the cartographer’s final draft, as thin blue lines. Often, a network of converging shorter lines, each with a defined beginning, join to form larger streams like Pleasant run and Holland brook.

These obscure water sources fascinate me simply because their anonymity and remote location arouses curiosity. Their presence also represents a convergence of habitat types that attract birds and wildlife. Though they bear no labels to honor their faithful contribution to the next blue line and ultimate confluence, their importance should not be overlooked.

Many springs which appeared on old maps no longer exist, eliminated by construction of sewer lines or filled in. As maps are revised and generations fade, these streams exist only in a cartographer’s archive.

My appreciation for these disappearing blue lines was heightened when I recently discovered that as a kid, I walked over Slingtail brook every day on the way to school. At some point this little stream was diverted through a sewer line under the pavement. More amazing, even older residents had no memory of that stream whose name has been lost to the ages.

An extended winter freeze, preserving snow from a previous storm, beyond its expected stay, was interrupted by a thaw and heavy rain. The melting snow joined the torrential rain as it flowed over frozen ground to collect in every shallow crease leading to the river. The water’s velocity was enhanced by the decreasing gradient of deep well-worn pathways etched in the earth.

Where water barely trickled most of the year, a proportional biblical flood now ensued.

The banks of the successively larger streams barely contained the accumulation of water delivered from the network of anonymous thin blue lines. Acting as a single entity, the collection agency if you will, the Raritan River drainage, faithfully delivered its contribution of sweet water to the world’s salty oceans.

Cattail brook arises from the convergence of a network of bubbling springs, supplemented by runoff from rain and snow fall. It begins as hardly more than a trickle, directed by gravity, from the south facing ridge of the heavily forested Sourland mountains. The DNA extracted from a drop of water, taken from the deepest canyon in the ocean, would trace its lineage back to cattail brook through its genetic progeny. Cattail gives birth to Rock Brook, a tumultuous and moody stream that joins the more sedate Bedens brook on its way to the Millstone river. The Millstone brings its accumulated genetic material to blend with that of the Raritan to make a final contribution to the earth’s deep blue oceans.

We use our imagination as we await the technology that can trace the oceans DNA back up Cattail brook to show a single drop of morning dew that dripped from a box turtles face, was a critical contribution to the blue ocean we see via satellite images of the earth.

Rock brook derives its character from the influence of gravity which changes its mood from an idyllic mountain brook to a raging torrent.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

A Red fox fills out a page in its daily diary, handwritten in the fresh snow along the South Branch.

The thirty-one days allotted to January on the calendar is only a suggestion, as far as that month is concerned.

January arrived ahead of schedule this December in a fit of impatience at the slow start of winter. The dull cold and dark days that prefaced winter’s birth seemed to stall the arrival of January and the blistering pace of expanding daylength and razor sharp cold.

As December reflected on the satisfaction of delivering twins, in the form of winter and light, the cold, wind and snow remained idling in the dark, awaiting a new leader. January came to the rescue as it honed the sharpness of the cold to a razor’s edge with forceful arctic wind, in whose draft, daylight was pulled along at an accelerated pace.

The whirlwind that is January never rests as it constantly delivers snow and light wrapped in cold and often spiced with biting wind.

Despite being scheduled for 31 days, January makes the time fly along with everlasting snow and does its best to co-author February weather.

In an attempt to freeze time so it can linger longer than scheduled, January’s frigid breath turns the river’s surface into a crystal lattice of solid ice. Impressive, but not miraculous and arguably unintended.

It is actually possible to watch January at work as it arranges hydrogen and oxygen atoms into a three-dimensional arrangement as it forms ice. A fast-moving cold front dropped the temperature below freezing. The river water was already cooled to 38 degrees and colder in the shallow eddies along the shore. As I fumbled with my camera I noticed ice forming along the edges of one pool. Crystals began to grow from a branch, mid pool, as well as the edges. When I looked again a few minutes later, the ice had expanded several inches. It was like watching a time lapsed movie where time is condensed from hours to seconds. However, this was happening in real time. I was amazed how quickly ice was forming. Crystals grew especially fast from three different areas. Two looked amazingly like feathers, one mimicked a large bird feather while the second looked so much like the cut feather used to fletch an arrow. The third crystal was an exact image of a starburst, where five pointed spikes began to outgrow the shorter but expanding tines. I stared in amazement as the ice images grew before my eyes as if watching an artist at work. The arrow feather magically turned into the body of what I imagined to be a grouse. The other feather grew into the body of some other large bird, the intricacies of each quill carefully detailed. Ice grew from the edges until the sheltered water had been completely sealed with a plate of fine transparent etchings. Though the artist was invisible, evidence of his existence was apparent.

January may seem harsh at times but all life has evolved to cope with its overly enthusiastic nature. As a concession, January snow provides a comment section for life along the river to tell their stories. Even the wind has the opportunity to take a single blade of grass and delicately etch its thoughts into the blank white slate.

A gray fox reveals its path and daily activity, as if written in an open diary, from the moment it left its sheltered nook to the strategy used to capture a tasty vole and the heart of a January love interest.

Fox tracks in the new snow with strands of straw colored grass bathed in the contrast of subtle light changes would make a fine Christmas card from the fox. The tracks convey a signed message that translates even to those who aren’t conversant in the language of ‘fox’.

A page purloined from the fox’s diary reveals its thoughts and activity written in the January snow. The fox stopped here atop a snowdrift to scan the area ahead for a meal or a mate, whichever came first.

Loathe to depart, January wills its wintry legacy to February who politely accepts it to bolster the enthusiasm of the fading winter.

December is as far as the year will take us, though fear not, January awaits holding the door to a new year wide open with a welcoming ice cold wind to ensure we enter fully awake and energized.

A red fox is a magical creature but even a fox cannot walk on water unless January turns it into a crystal lattice. This fox crosses the river, lured by the siren call of a potential mate.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Portrait of a sycamore branch with a fox in the background. Female fox was so intent on her early morning hunt, I was able to get within 30 paces before she noticed me.

Snow follows December like a lazy white shadow that lingers in the bright light of day. A shadow of some substance that accumulates to measurable depth, can be blown about by the wind and reveal hidden secrets of elusive wildlife.

The stillness of a cold overcast day can foretell the coming of December’s white shadow, soon to arrive. The first flakes drift slowly to earth as the shadow begins to appear. A single snow flake landed intact on my wool mitten, suspended on an errant fiber. The intricate artistry nature expressed in this one crystal represented the beauty of uncountable trillions more. The hidden beauty, however, is often lost as the shadow deepens.

Falling snow covered me and my canoe as I sought safe harbor in a narrow slush filled stream bordered by high banks. The canoe was stabilized in the slush and I felt comfortable adjusting my gear to warm my hands. As I sat hunched over the snow began to build, essentially hiding me within its shadow. Suddenly a large male mink came loping through the deep snow, intent on crossing the small stream. My snow-covered boat must have been a welcome bridge to avoid the icy water. Just as the mink, now four feet away, was about to jump into my boat, he suddenly caught my scent and retreated into a nearby groundhog den. This was a unique situation, where I saw what happened and then in hindsight, was able to read the story the tracks left in the snow. It was like being at the scene of an unfolding drama and later watching it in a news report.

Mink trail in the snow and tracks in the mud.

I followed fresh fox tracks one morning not realizing how fresh they were. With the wind in my favor and dressed in white coveralls, I walked along observing where the fox stopped to sit, waiting for sound or scent to betray the location of a mouse under the snow. Apparently, nothing materialized, as the fox continued on its original straight-line path, stopping again to listen for a scurrying mouse hiding deep within in December’s white shadow. Here at last were telltale signs the fox made an attempt to catch the elusive rodent.

From a sitting position, it shuffled its hind feet and leaped several feet ahead, going air born before landing and stomping around and stabbing its face into the deep snow. The absence of blood or fur suggested the effort was futile as the fox continued on, heading toward a large pile of tree branches deposited along the riverbank by a previous flood. I looked up from the tracks in the snow to see the fox a moment before it saw me. I had only a split second to react and get the camera focused. We were only thirty steps apart as I digitized the suspicious fox staring back at me. Neither of us moved for a long moment until the fox slowly turned, began to walk away and then stopped to pee. Perhaps she was expressing her displeasure at having her hunt disturbed and left her scent to reaffirm ownership of her home territory.

Fox tracks in the new snow with strands of straw colored grass bathed in the contrast of subtle light changes would make a fine Christmas card from the fox. The tracks convey a signed message that translates even to those who aren’t conversant in the language of ‘fox’.

December’s telltale shadow is an open book even the wind uses as a message board. Capable of producing destructive storms of biblical proportion, the wind shows its gentler side, using a single blade of grass to whimsically etch it thoughts in the snow.

December owns the darkest days of the year and when the moment of darkness is greatest, at the instant of the winter solstice, it gives birth to light as day length begins to increase. Light or dark, December’s shadow is not far behind, casting a trace of white.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

The food chain is not a one way street, as a turtle whose kin may feed on baby ducks, gets picked on by a bald eagle

It is unthinkable to imagine a restaurant where the diners are often listed as menu items. Though when seated at nature’s dinner table, the catch of the day takes on a whole new meaning as predators and prey freely alternate position. The dietary choices are also a surprise as the variety of delectable meals is often at odds with expectations.

Sorting through my library of photos, I was perplexed trying to categorize some images showing two species in close contact. Obviously notable was the reversal of who was eating who.

The first image which prompted these thoughts was captured as I launched my canoe. Here was a very young painted water snake, brilliant colored markings, with a fish sticking out its mouth. Comparing the size of the snake to the fish, I wondered if the snake ‘bit off more than he could chew’, as they say. The fish was wider than the snake and it didn’t look like much progress was being made in the attempt to swallow it. I couldn’t identify the species of fish but thought it a moment of karma as small mouth bass which inhabit the river are well known to forage on anything that swims or crawls in the waters of the south branch. A small snake would hardly be ignored by a hungry bass.

Another image shows a larger painted water snake suspended on o vertical river bank holding onto the tail of a gold colored catfish. As the snake was in an awkward position and didn’t want to go into the water, it was a standoff with the advantage going to the snake. The fish would struggle and then lay still. Eventually the fish broke free. I then remembered a series of images documenting another struggle where a snapping turtle grabbed a painted water snake by the tail. As I paddled along, I saw a water snake swimming across the river and as it neared the opposite bank it suddenly reared up and began to thrash about. Mystery solved as a snapping turtle soon surfaced holding on tight, as the snake now alternated struggling and lying still. As I drifted closer, the turtle was intimidated into releasing its grip and the snake swam off.

A painted water snake has a catfish by the tail. The snake is barely holding on to the vertical bank , using a tuft of grass to secure its precarious position. the catfish would struggle mighily and then rest. After several tries the catfish appeared dead and lay still for quite some time. Suddenly the catfish came to life and broke free. Again, the scene was captured from a canoe.

A painted water snakes has the tables turned on it as a snapping turtle reached up to grab the snake swimming across the river.

Turtles are not immune from the proverbial soup bowl as they are prey to many birds and animals that share the same habitat. Even large water snakes will easily swallow a turtle hatchling seeking cover in the water, as will great blue herons, mink, fox, skunk, raccoon and birds of prey.

In a twist of fate, the turtle that killed baby ducks in a farm pond yesterday could very well be on a larger bird’s menu today.

Such was the case when I spotted a bald eagle standing on a log near shore, intently pulling and tearing away at what was probably a deer carcass or white sucker. The eagle would occasionally look up and certainly it saw me from two hundred yards away, apparently not at all intimidated. As I closed the distance, a bright yellow object was clearly visible and the focus of the eagle’s rapt attention. I began to take photos, drifting ever closer and as I started to pass the eagle, it flew off. It was then I realized the eagle was dining on a painted turtle!

Across the land where rivers flow, the lines between predator and prey begin to blur. Don’t be surprised when a squirrel is seen carry a baby crow or a muskrat is swimming underwater holding a baby blue jay or a blue jay is flying off with a dead vole. If you can’t imagine it, it is happening somewhere along our wild rivers.

Muskrat with a bluejay swims into its den’s underwater entrance. Mystery for sure.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Black oak leaves are ablaze in the most incredible orange color, which makes you wonder how the black oak got its name.

A robe of many colors is October’s alone to wear. It is a coarse cloth, woven with silken threads of yellow and orange, melting into the extreme end of the red spectrum. Set against a clear blue sky, the colors radiate with brilliance. While the sun is otherwise occupied behind gathering clouds, the colors are no less extraordinary, as they hold their sharp contrast, presenting with a soft matte finish.

As the robe is placed upon the earth’s shoulders, the colors slowly flow downward in an infinitely slow progression, best seen from high above the earth. With that image in mind, it is easy to visualize autumn as a living creature leaving a momentary trail of color across the breadth of the tilting earth.

An alternative to a live, time lapsed satellite image of autumn’s gradual crawl across the latitudes, is best seen from a lofty vantage point with expansive views. Though the view is static, the full range of colors is on display. The cloth of the colorful cloak lies tight against the contour of the wooded mountains, each undulating feature of the landscape accentuated by shade and light. On a typical sunlit October day, herds of white billowy clouds drift across the blue sky followed on the ground by their shadows trying to keep up. As the lagging shadows flow across the colorful mountainsides, the tints change for a brief moment to provide a sense of movement to an otherwise still image. The scene is more dramatic if you can imagine the passing shadows being that of the artist’s hand working as you watch.

Retreating from distant views to stand within the October woodlands, individual trees and stands of trees become the focus. Each species resplendent in their own genetically defined color, modified to some degree by soil conditions, specifically, available nutrients and moisture. Instead of looking at a mass of treetops where smudges of varied colors blend together, we now see the pixels that make up the distant image.

Comparing trees of the same species, we can see the individual variation of color. Many trees with yellow leaves such as hickories, Norway maples, cherry and tulip poplar trees are very consistent in color. Oaks, sweetgum and some maples, whose leaves have a red component, show the most diversity.

The most glorious displays of fall color are where we find them, scattered among the local landscape. Each, an emissary heralding the arrival of autumn; apart from the mass of color sweeping across the land.

We all have a perennial favorite we watch on a daily basis to gauge the progress of autumn color.

A lone white oak in the middle of a field or a native red maple pressing against the chain link fence in the backyard, as seen from the bathroom window, serve as daily alerts.

Among the many autumn images accumulated in my experience, the one that keeps appearing is an old abandoned farm road lined with Norway maples, all the same size. The tree tops form a tight canopy over the road, keeping it clear of weeds and paving it with a golden carpet of fallen leaves. The length of the yellow paved road has a hint of a vanishing point that beckons a traveler to follow deeper into the fire of autumn color.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.