The water world around us we do not see: Stormwater sewers

This is the first of three articles in a series about stormwater management by Kate Douthat, a third year PhD candidate in the graduate program of Ecology and Evolution at Rutgers. Kate’s research is examining the plant communities that have formed in urban stormwater systems. She is interested in the extensive stormwater infrastructure network in New Jersey and how we can use plants to improve water quality. Kate loves to share her enthusiasm about plants and to teach the public about the stormwater systems in our backyards. She has agreed to develop a series of informative blogs for the LRWP’s readers and will also lead our #booksfortheriver book club starting Fall 2019. You can see more of her writing about plants and water resources on katedouthatecology.com

When it rains, water runs across roads, parking lots, and lawns, picking up pollutants and debris. In order to prevent flooding in developed areas, where the soil is not absorbent because it is covered by pavement or buildings, this runoff, termed “stormwater,” is channeled into storm drains. In nature, wetlands play an important role in the landscape as regulators of flood waters and sinks for excess nutrients and pollutants that are swept up in storm water. Green infrastructure is an approach to water management that mimics natural storage and filtering functions of wetlands by using plants and soils rather than drains and pipes. We don’t yet have a good understanding of which plants are best suited to green infrastructure, so that is the topic of my research.

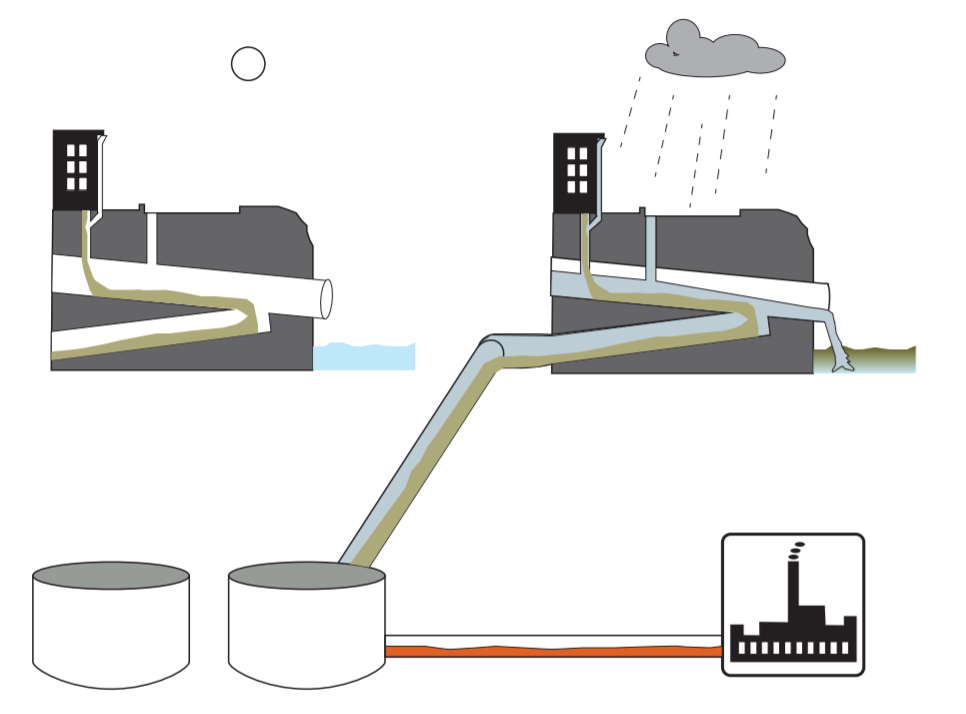

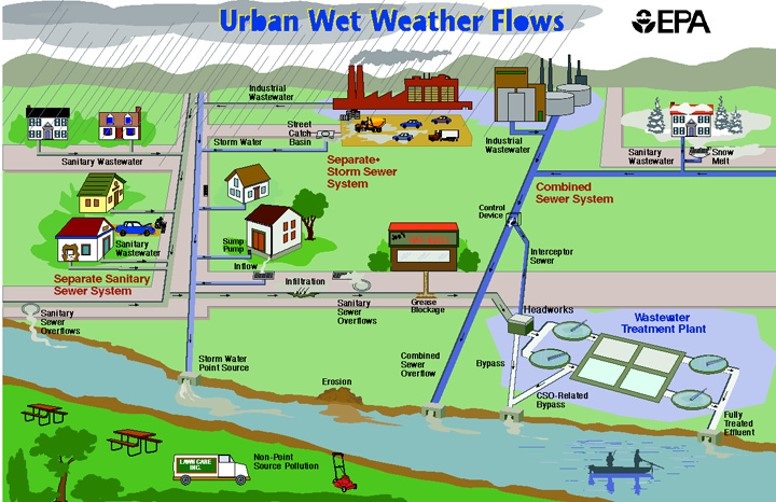

Once stormwater enters a drain, it can have different fates. One type of municipal sewer system is called a combined sewer system. A combined sewer system combines sewage from your house (toilet sewage) with stormwater runoff from storm drains. This creates a large volume of contaminated water that must be treated at water treatment plants. This type of system is more common in older cities in the U.S., and in 21 cities in New Jersey (https://www.nj.gov/dep/dwq/cso-basics.htm). In New Jersey, most combined sewer systems are in cities near NYC, and a few around Philadelphia. The NJ Department of Environmental Protection hosts a web map to show those locations.

The second type of sewer system is a separate system. A separate system keeps sewage containing human waste in one set of pipes, and stormwater runoff from storm drains in another set of pipes. The latter has the the witty nickname MS4 (municipal separate storm sewer system). The sewage goes to a waste water treatment plant, while the stormwater is released to streams or rivers. This relieves pressure on waste water treatment plants and prevents overflows of untreated sewage. However, stormwater is usually contaminated with all of the urban dross it picks up, including pet waste, leaked gas and oil from our cars, excess lawn fertilizers and pesticides. Stormwater moves more quickly over smooth, paved surfaces than rough natural ones, so stormwater can accumulate quickly and cause floods.

In New Jersey and many places in the U.S., water from storm drains is temporarily stored in artificial detention basins or ponds before draining to streams and rivers. In principle this prevents the water from a rain storm from concentrating in a stream all at once and flooding its banks. A detention basin receives water from the storm sewer, then passively allows it to drain out the other side. The outlet pipe is small though, restricting the water leaving the basin to a low, steady volume. Detention basins were originally designed for flood control, but we are now realizing that they could be redesigned to provide more functions. The expanded functions for detention basins include pollutant filtering, ground water recharge, and provision of habitat.

Most detention basins are lined with grass that is mown weekly or biweekly like a lawn. In order to increase the functions of the basin, managers are changing to a mix of dense vegetation that is mown annually. This simple change can have a big impact and is the subject of my research. In my next post I’ll talk more about why I’m interested in studying detention basins, what I hope to find out, and how it can change our watershed for the better.