Ganesh Chaturthi – or Vinayaka Chaturthi, Chavath, or Lambodhara Piranalu depending on where you live – is one of the biggest Hindu festivals of the year. Occurring at the end of India’s four month monsoon season and at the beginning of the harvest season, Ganesh Chaturthi invokes the elephant-headed God Ganesh for a bountiful harvest.

There is a lovely environmental meaning to the Ganesh Chaturthi festival. Ganesh idols were originally fashioned from the clays of area water bodies prior to the monsoons so as to clean the waters of silt deposits. Part of the festival involves Ganesha devotees celebrating their local region’s natural history by gathering 21 symbolic non-agricultural medicinal plants for inclusion in an offering to the idol. Traditionally at the end of the festival the idols were returned to waters from which their materials were taken, often with the plant and other offerings.

Ganesha and 21 leaves offerings – from www.thespiritualindian.com

In the past decades, Ganesha idols in India and the United States have been constructed out of non-biodegradable Plaster of Paris, plastic or metal, and painted with toxic paints. And it is often the case that idols are abandoned in rivers, lakes, streams or the ocean at the end of the festival. These idols can take several years to fully dissolve, if they dissolve at all. This leads to lowering of oxygen levels and contamination of our water bodies. Unfortunately the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and partners have found many dozen abandoned idols in area waters over the years.

Ganesha idols found in the Raritan River on September 20, 2018

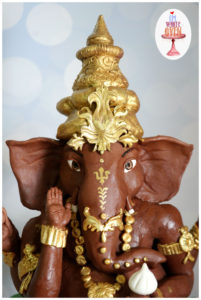

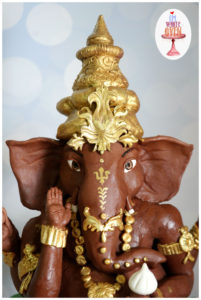

As the negative environmental impacts of abandonment of Ganesh have been recognized, practices have been adopted to minimize these impacts. Increasingly clay and mud idols are crafted with a seed inside them, painted with non-toxic rice paste and vermillion, and then buried or planted in home gardens instead of being immersed or abandoned in area waters. We have also heard about a new way of making the Ganesha idol: that is by using modeling chocolate. The Ganesha idol is made using chocolate, and at the end of the festival the idol is immersed in milk. The chocolate is then distributed among celebrants, or provided to the homeless.

Chocolate Ganesha – it dissolves in milk!

In the United States it is a violation of the Federal Clean Water Act to pollute or discharge ANY items (biodegradable or otherwise) into waterways without a permit. It is now the case that many Hindu temples and other other cultural institutions secure permits for temporary immersion of the idols in the Raritan River and area streams. That is, celebrants bring their Ganesha to a public ceremonial immersion event and then reuse their idols the following year. We applaud those who celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi in an environmentally friendly fashion.

For those who celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi we wish you happiness as big as Ganesh’s appetite, life as long as his trunk, trouble as small as his mouse, moments as sweet as modaks, and a healthy and clean environment in which to honor Ganapati and his gifts. Happy Ganesh Chaturthi!

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Shades of fluorescent orange, used to color the dawning day, dripped from the palette of the celestial artist to set the autumn woods on fire.

Shades of fluorescent orange, used to color the dawning day, dripped from the palette of the celestial artist to set the autumn woods on fire.

Waves of celestial orange roll over the treetops to set the autumn woods ablaze.

The white, early morning autumn mist hung motionless above the flowing dark water of the South Branch. As dawn approached, the rising sun turned the eastern horizon into a glowing red-hot coal that lit the pale mist with an orange blush.

The trees along the river were immersed in the flood of pre-dawn mist. Some completely hidden and others partially protruding as dark brown silhouettes floating adrift on a misty sea.

As the sun arose, it was as if watching an artist at work laying base colors and adding tints to bring a charcoal sketch to life. The changing light and rising temperature caused the orange mist to vanish as entire trees appeared from the mist, revealing splotches of vibrant fall color.

It is easy to imagine the changing colors of the sunrise were infused into the river mist to wash over the treetops and set their leaves ablaze.

The same spectrum of color seen in the eastern sky at dawn can be found in the fall foliage not flooded by river mist. The full visible spectrum from violet through red and orange, to pink, salmon and yellow are shared as the tree tops meet the sky’s loaded paint brush.

A mere splash of color in early autumn is all that is needed to set the late October woods ablaze. Each living drop of color slowly expands to cover the entire leaf as the season progresses. Its radiance now sets adjoining leaves aglow until the entire woodland canopy is bathed in bright color.

Retreating skyward to a time lapsed satellite view, the expanding colors can actually be seen migrating south. The green foliage appears to be consumed by the advancing flames of the autumnal fire.

Poetic inspiration imagines it is the weight of intense color that causes the leaf to depart the branch.

Gusts of wind stir the treetops to recruit a shower of shimmering color in a free fall final dance for which the tethered leaves had been rehearsing since spring.

The first leaves to fall are contributed by the black walnut and ash trees. Impatient for some reason to drop their leaves. They stand naked among the still well-dressed oak and maple associates just beginning to change color.

A stand of Norway maples grew thick along a low ridge that bordered a sloping cornfield. Their brilliant yellow leaves carpeted the ground and reflected light upward to brighten the understory and set the leaves aglow. The lowest leaves fought for their share of light all season and grew oversized in the effort. The reflected light penetrated the deep shade to illuminate these outsized yellow beacons to celebrity status.

The change of leaf color during autumn has a well-established scientific explanation. Though a longer held belief declared, without question, the color was the work of an ethereal magician.

It is easy to subscribe to that belief when you see a green leaf turn fluorescent orange, a color otherwise unknown in nature. The only place to see that color was in the flames of a fire or in the distant heavens to mark the sun’s arrival and departure.

The fall color is best seen as magic, to set your imagination free and escape to a quiet place where all things are possible.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and Photos by Margo Persin, Rutgers Environmental Steward

Editor’s Note: In 2018 Margo Persin joined the Rutgers Environmental Steward program for training in the important environmental issues affecting New Jersey. Program participants are trained to tackle local environmental problems through a service project. As part of Margo’s service project she chose to conduct assessments of a local stream for a year, and to provide the data she gathered to the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP). Margo keeps a journal of her experiences, excerpts of which are included in the LRWP’s “Voices of the Watershed” column.

Internship Diary / August, 2018

For this visit to my assigned assessment site, I had new members of my ‘team’. It so happens that two of my godsons were visiting from London, UK, where they reside and go to school. Alex, 14 years old, and Mathieu, 12 years old, were presented with the option of participating as full team members to do a stream assessment at the Ambrose Brook. They readily agreed, and we set off for the stream site.

The day was partly cloudy upon arrival and proceeded to get more clouded over as our time at the stream advanced. I appreciated very much the extra eyes and hands, given that it would take a group effort to undertake and finish all the measurements required of the assessment. It was so nice to have the company and the opportunity to share this activity with them. They asked some pertinent questions in regard to the site, as well as concerning the focus of the project. We were armed with marker flags, tape measure and ruler, thermometer, stop watch, and the required forms to fill out. In addition, as a nod to my own childhood, I had dug out of storage the red plastic duckie that I had used so (too) many years ago when I was a child. After having sealed the seams with glue, it proved to be water ready and floatable, and was thrown into our equipment bag.

Upon arrival, we did a quick survey of the site. I gave the boys an overview of the project as we walked the required distance to mark off where we would take our measurements and set our marker flags. We were not particularly surprised to note that summer was on the wane, and the stream site showed the effects of the copious summer rain fall of this year and the subtle yet visible march of time on the greenery. There were a few trees already beginning to drop some leaves, apparent at their base as well as at the edges of the stream. Some windfallen branches had made their way into the stream on both sides, evidence of the frequent storms that had buffeted our area during the preceding summer months. In addition, the water level had risen, as marked by mud splashes on bushes, trunks and the mud banks. There were a few ducks and Canadian geese, who had vacated the surrounding lawns and walkways; that day, they were floating lazily on the water’s surface between the far bank and the island, oblivious to our presence.

Ambrose Brook, August 2018 – Margo Persin

High water at Ambrose Brook, August 2018 – Margo Persin

At that point, the boys and I got to work. Alex and I did the physical measuring, including wading to the middle of the stream to measure depth and velocity, while Mathieu took on the role of scribe and stop watch handler. The first order of business was to observe, consult and come to a shared decision in regard to water conditions. My team mates took their jobs seriously and we were able to arrive at mutually acceptable readings of turbidity and stream flow. The next order of business was to measure width, depth and velocity. Armed with the rubber duck and ruler, Alex waded to the starting point while I headed in the opposite direction. Mathieu had been instructed in the subtleties of the stop watch, and as the two of us with wet feet called out the various measurements and Mathieu proceeded to fill out the form. All of us – Alex, Mathieu, me, and the rubber duck – showed ourselves up to the task and we were able to finish that part of the assessment in due time.

After exiting the stream, it began to rain, so the three of us made a mad dash back to my vehicle, where we took refuge and worked through the rest of the form. The boys were more than willing to express their views in regard to stream characteristics as well as all the elements of high gradient monitoring. We reviewed the results in order to make sure that we were of one accord in regard to our observations and conclusions. They did a wonderful job of giving themselves over to the project, with determination, seriousness, intellectual curiosity, good humor, and dedication. After approximately one and half hours, we took our leave and headed to a nearby ice cream parlor for a well-deserved reward. Their company and participation were most welcome and I hope that this experience will inspire in them the desire to become involved with environmental projects of their own, whether on their own or in conjunction with their school curriculum.

Article by Maya Fenyk (age 14), photos by Joe Mish and Karen Byrne

Sedge Island Field Experience youth after relocating an osprey nest, photo by Karen Byrne

In mid-August I had the opportunity to be part of the Sedge Island Field Experience (SIFE), a program run by the New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife. Through SIFE I learned about the ecology and history of the marshes in the Barnegat Bay Area, and to study the area’s wildlife including birds and bugs. At the end of SIFE, campers have an opportunity to present what they have learned throughout the week on topics of their choice. I chose to do a presentation on a threatened species that is found in both the Barnegat Bay area and in the Lower Raritan Watershed, osprey.

Osprey are beautiful and distinctive birds, with brown feathers covering their back and wings and white feathers covering their stomach. Their heads are also a brilliant white, with a dark eye mask (similar to a raccoons). The osprey are also very big birds, with their height being typically 21-24 inches and their wingspan being 4 feet 6 inches-6 feet. Their voice is also distinctive, loud, high pitched and musical, like a cheeep cheep cheep.

Osprey, photo by Joe Mish

Osprey are not only beautiful birds but they are extremely important to every area they inhabit because they are an indicator species. An indicator species is a species that indicates the level of pollutants in different areas just by where they choose to make their homes. Since indicator species are very pollution sensitive, they won’t choose to live in an area where there is a lot of pollution. In this way they indicate that the level of pollution in the areas they inhabit are fairly clean. Where ospreys choose not to make their homes also indicates the level of pollutants because if there is an area that historically has been the osprey’s home, and osprey are not found there, we know that something is telling the osprey to stay away. Once we know that something is wrong, environmental conservation agencies can then determine the cause and hopefully bring the osprey’s back once the problem is fixed.

Osprey are a migrating species and have a range which spreads across the entire continental United States, the majority of Central and South America and some of Canada. Ospreys make New Jersey their home during their breeding season, which extends from April- August. After breeding season they begin their long trek to Central and South America to countries such as Ecuador and Colombia where they spend their winter.

Unfortunately, ospreys are less common in New Jersey than they used to be prior to the development of their habitat and the inadvertent poisoning of them in the 50’s and 60’s due to the use of the pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), used for mosquito control. Though osprey did not consume the pesticide directly, they were poisoned through the process of biomagnification. What this means is that when mosquitoes were treated by DDT, fish then consumed the treated mosquitoes, ingesting DDT themselves. Then when the osprey consumed the fish the concentrated DDT affected them as well. Every time an animal consumed another animal the amount each animal consumed was magnified exponentially. Another effect that DDT had on osprey was that it made their eggshells very brittle and thin so that when the mother osprey went to sit on her eggs, they would break, killing the unborn hatchling.

In 1974 there were only 50 active osprey nests in the state of New Jersey, and that was the point when the New Jersey Department of Fish and Game (now New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife), through a program led by Paul D. “Pete ”McClain stepped in. The program brought hatchlings and breeding pairs from Maryland to the Barnegat Bay area to increase the population in New Jersey. The osprey are now protected through State and Federal Laws. They have been taken off the endangered species list and moved to the threatened species list. Forty years ago there were only 50 breeding pairs in New Jersey, but there are now 700 breeding pairs, including many juveniles. Even though the osprey are out of immediate danger, they still need to be protected and their habitats still need to be conserved. Many threats still face the osprey and only 50% of juvenile osprey live to adulthood.

So, what are people doing today to protect the osprey? During my SIFE week I had an opportunity to work to protect the osprey.

Due to the development of their habitat in the Barnegat Bay area, specifically creation of a canal that removed their roosting lands, the osprey now must live in man-made platforms. Through the SIFE program I had the opportunity to relocate an osprey nest from direct contact with an kayak/canoe trail to a place with more limited human contact. The New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife was concerned that the prolonged contact with humans through the osprey nest being on a trail would lead to the abandonment of that nest and thereby decreasing Barnegat Bay’s population of osprey. See the photos below for a visual story of how our group relocated an osprey nest.

The day after we moved the osprey roost, osprey had already moved in, seemingly happy with their relocated home. I was extremely lucky to have the opportunity to help the osprey in such a way, and I recognize that not every can do that, so I encourage everyone to find their own way to help ospreys like making sure that their environment is clean and even donating to organizations who are monitoring and taking care of the osprey. Everyone can help get the osprey off the threatened species list, what are you going to do to help?

Sedge Island Field Experience youth move an osprey nest, photos by Karen Byrne