The Eagle Has Landed

Article and photos by Joe Mish

When the Eagle Lunar Lander set down on the moon in 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong spoke these immortal words, ‘the eagle has landed’.

Those simple words announced to the world that the man in the moon finally had company. The proximity of the moon to the earth made it a central part of myth and legend and directed human behavior as if it were a nurturing celestial caretaker. That humanity now stood on the moon was unbelievable, the impossible had now been achieved!

That headline, ‘the eagle has landed’, perfectly described my emotion when I scanned the latest NJ eagle report and saw an image of an eagle nest and the word, ‘Keasbey’, as its location. I was stunned as a range of emotions swept over me. Keasbey? Eagles? Eagles associated with Keasbey? The same Keasbey I intimately knew from my youthful wandering among the swamps, streams, and tidal creeks in the 1960s and 70s?

Previously, the only reference to eagles in Keasbey were the Keasbey Eagles, a weight lifting club on the Keasbey Heights overlooking Raritan Bay. Another reference was Eagleswood, a utopian society situated along the shore of Raritan Bay, which ended at what is now the Keasbey border. Visiting naturalist, Henry David Thoreau, linked Eagleswood to Keasbey when he described in his journal on November 2, 1856, a walk two miles upriver from Eagleswood in Perth Amboy to what is now the Keasbey shoreline.

A wooly mammoth might sooner be unearthed in a Keasbey clay bank than the shadow of a bald eagle pass over the land. Eagles existed only in far-away pristine wilderness destinations.

For that matter Canada geese were unknown to the area, mallards were found only in parks and on occasion a deer track might be seen and be a cause of conservation.

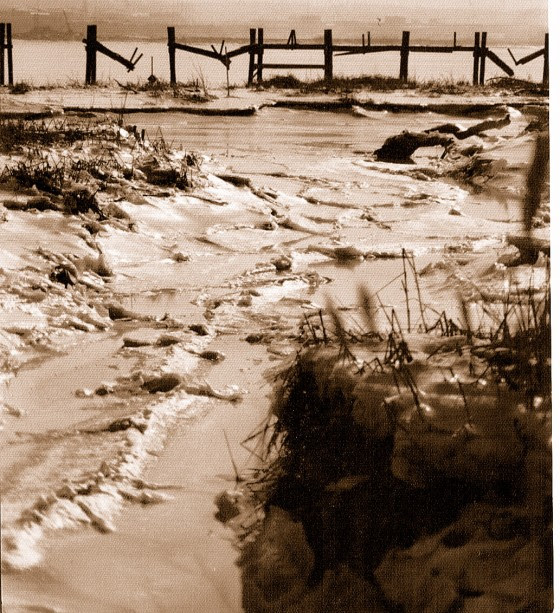

Crows Mill Creek, whose source was a clear spring, now tinted acid yellow, after passing through HR Grace property, flowed over the sandy bottom to the tidal creek at Jennings boat yard. HR Grace, Hayden Chemical Company and Hatco dominated the spring fed area. Some nights, downwind of the factories, the wind might burn your eyes, and in the morning, white flakes would cover your car.

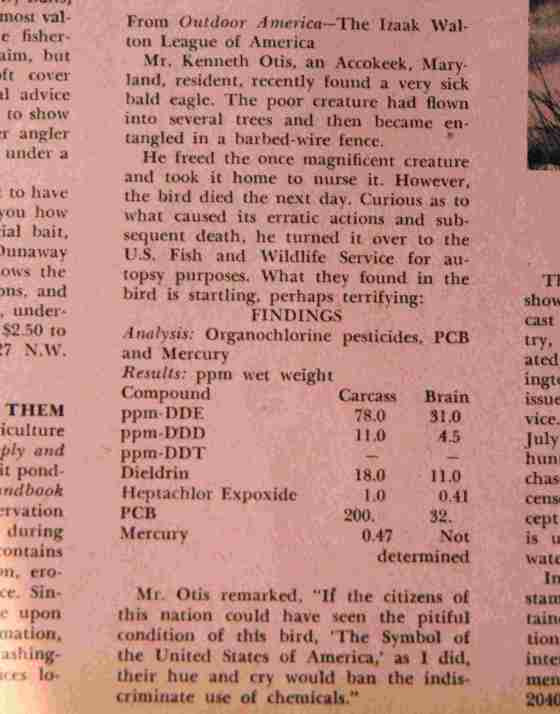

During the summer when mosquitoes were nigh, an olive drab military vehicle would ride up and down the streets spraying thick clouds of DDT, through which all the kids rode their bicycles. Keasbey itself had rerouted Crows Mill Road around a large abandoned clay pit and used it to dump garbage. Upstream of Keasbey, in Edison, the Raritan Arsenal buried weapons and explosives in the wetlands along the river. Within the Arsenal property, Phosgene was buried in small isolated fenced in areas. National Lead was situated across the river, lead slag was used to support the shoreline in many locations along the Bay. Lead, among other chemicals, entered the food chain to accumulate in top feeders.

The lower Raritan and Keasbey were in no way suitable eagle habitat, even though the Raritan is a major migratory extension of the Atlantic flyway. The lower Raritan region is one of, if not, the most naturally diverse regions in the state, it is where the soils of south Jersey meet the soils of the north. From the soil springs a diversity of plants and a cascade of wildlife to make this region a veritable United Nations where all members are represented in one location. This cannot be emphasized enough, the potential for diversity is critical to build upon the success of the eagles. In fact, it is stunted, to look at a single species and not the community in which it exists.

While remediation of the chemical factories is underway and DDT use curtailed, we are still plagued with legacy pollution and a spectrum of novel emerging pollutants. Microplastics combine with pharmaceuticals and other chemicals to attack the immune system of humans and other top food chain feeders such as eagles. Blood samples taken from eagles remain in frozen storage for lack of funding. Even if processed, there is no plan to look at the impact of specific pollutants on the immune system. The preoccupation with lead poisoning diverts attention from the impact other pollutants have on the immune system. We hope the exploding eagle population is not a flash in the pan and only time and further research will tell.

So, the table had been set for an explosion of natural diversity denied by decades of abuse. When one lives to see the dramatic contrast take place over a lifetime, the impact approaches the status of a miracle. The nesting bald eagle in Keasbey is on the level of man landing on the moon, a cause for celebration in and of itself.

To delve a bit deeper into pollutants, see the NJ fish consumption warnings

https://dep.nj.gov/dsr/fish-advisories-studies/

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author. Contact jjmish57@msn.com.