Tag: Rutgers

Enjoy Nature While Nurturing It: Clean Up Edition

Article by Caleigh Holland, written as part of the Rutgers Spring Semester 2019 Environmental Communications course

It is no secret that pollution is a problem in our oceans; we know that plastic bags and straws are killing sea creatures. However, the public is not always as aware of the pollution in local rivers and the consequential damage it is costing us and the environment. The Raritan River is unfortunately full of garbage from littering and industrial facilities, as well as polluted by raw sewage. How can you as the public help an issue that impacts your drinking water, local wildlife, transportation, and recreational activities? An opportunity to aid in the health of our environment is to participate in a river clean up. This weekend activity or weekday afternoon would allow you to not only enjoy the outdoors, but bond with a group of people that share the same goal.

Who can join in a clean up?

The Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP) is happy to have volunteers join them for service; you can connect with them through their website to find clean-up opportunities, or to share ideas for clean-up locations. Participating in a stream or river clean-up is a great community-building activity for groups of all sorts. Faith-based groups, Rutgers environmental and outdoor clubs, and local charities can sign up to help out. In addition to the LRWP, several other local organizations regularly host clean ups, and organizations like American Rivers help groups schedule river clean ups and offer advice to the public on how to create a successful event.

What are the safety precautions for the river clean ups?

For most clean-ups protective gloves are provided.

Participants should ensure that they have proper footwear, clothing for the season, bug repellent, hydration, and snacks.

The LRWP asks that volunteers leave glass, weapons, and drug paraphernalia where it is, and that they let a clean-up coordinator know about those and any other dangerous items.

Individuals under 18 need a parent’s signature to participate in formal clean-ups, and for every five youths under 12 one adult must be present.

Why we should clean up the river

There is a considerable amount of pollution in the Raritan River from a number of different sources. One kind of pollution of concern is microplastics, which are any pieces of plastic smaller than 5 millimeters. Microplastics are either created from the breakdown of larger pieces of plastic, are by-products of plastics production, or are used in products such as toothpaste or cosmetics. Researchers from Rutgers University have shown a high concentration of microplastics in local waters water.

Any plastic that is allowed to wash into the river such as through storm drains can easily end up in the water and over time will wear down and distribute itself throughout the river’s waters. If freshwater animals eat the microplastics found in the water and then humans eat the aquatic animals, there is growing research that suggests that the ingestion of plastics can lead to changes in our chromosomes which could lead to obesity, cancer, and infertility. There are potentially several health consequences to the public if we don’t clean up the Raritan River.

How much of a difference can you make cleaning up the river?

Although it may seem like a lost cause when you hear about the amount of pollution already in the river, a little goes a long way in terms of clearing the water of garbage. Over 20 years, the town of Manchester, NJ organized over 116 clean-up events with more than 1000 volunteers. In less than two decades they managed to collect 2,394 bags of trash which amounts to $78,000 in volunteer donation time. Organizations like the LRWP are trying to do the same along the banks of the old Raritan.

How can we clean up when there is no event scheduled?

A clean river starts with your daily routine. Recycle rather than throw out your garbage. Recycle your plastic shopping bags at local grocery stores. When you walk or jog outside, pick up garbage as you go. “Plogging” – picking up litter while jogging – is a way for you not only to promote a healthy lifestyle for yourself, but for the environment too. You don’t need to jump right in and get your feet wet—you can help the river by thinking more consciously about your own behaviors at home, at work, and in your community.

Effective communication about the environment is critical to raising awareness and influencing the public’s response and concern about the environment. The course Environmental Communication (11:374:325), taught by Dr. Mary Nucci of the Department of Human Ecology at Rutgers University, focuses on improving student’s writing and speaking skills while introducing students to using communication as a tool for environmental change. Students not only spend time in class being exposed to content about environmental communication, but also meet with communicators from a range of local environmental organizations to understand the issues they face in communicating about the environment. In 2019, the course applied their knowledge to creating blogs for their “client,” the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP). Under the guidance of LRWP Founder, Dr. Heather Fenyk, students in the course researched topics about water quality and recreation along the Raritan. Throughout 2020 the LRWP will share student work on our website.

Lower Raritan Parks – Ours to Enjoy

Article and photos by Gisela Aspur Chavarria, written as part of the Rutgers Spring Semester 2019 Environmental Communications course

Are you bored at home? If so, go to one of our local parks along the Raritan River and enjoy the outdoors. Highland Park offers various parks and abundant open space and recreation for residents and visitors. One amazing place to visit in Highland Park is the Native Plant Reserve. The reserve has a collection of native flowers, shrubs, vines, and trees, with educational signs for each species (1). The reserve is a fantastic place to drop by and explore nature. It’s also a great place to bring children of all ages to teach them about plants and their importance.

You can also visit the Eugene Young Environmental Education Center in Highland Park which uses art to raise awareness about wildlife and the significance of the Raritan River. In 2014, a mural was unveiled at the Eugene Young Environmental Education Center as part of a project to create artwork to highlight the river, and to make people aware of its beauty, and value (5).

Another extraordinary recreational place along the Raritan River is Donaldson Park which is located in the Borough of Highland Park. The park has boat ramps, kayaking, fishing, sports fields, biking trails, playgrounds, and paved trails (2). The picnic groves in the park are a great place for families to eat and spend quality time with each other.

Similarly, Elmer B. Boyd Park in New Brunswick is an amazing recreational space for community engagement. It provides walking and biking paths, a playground, and a boat launching space. Boyd Park also hosts many community events during the year, including the autumn River Festival, the Hispanic Festival, and the city’s Fourth of July celebration (3). You can also learn about the history of the river through the signage through the park. All of these parks are great recreational places for individuals and families to connect with the river and enjoy the outdoors.

Promoting River Access

But our local parks are important for more than just recreation, as they provide vital access to the Raritan River. River access encourages individuals to develop a relationship with the river and connect to our local environment. By connecting the community with the river, people develop a sense of ownership and care about the river and its future. Visual exposure to natural resources like the Raritan River prompt people to understand the importance of the river and the value it provides for the community.

Recreational activities by the river are wonderful ways in which individuals can connect with the river. Whether you canoe, fish, or walk along the river, access to river recreation inspires people to protect nature and wildlife. Furthermore, recreation creates a caring constituency for healthy rivers, lands, and resources, inspiring the preservation of important places. Thus, it can encourage communities to help control pollution and ensure natural resources are preserved.

Nature and Mental Health

Aside from the pleasure of enjoying activities along the river, recreation by the river can also improve your quality of life. Researchers have shown that exposure to nature is beneficial to people’s mental health, suggesting that accessible natural areas within urban contexts may be a critical resource for mental health in our rapidly urbanizing world (6). Exposure to nature can improve your mood and self-esteem, help you feel more relaxed, reduce anxiety, and help with depression (7). Significantly, a lack of nature experiences may contribute to a range of issues in children. In his book, Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv described how children are spending less time outdoors and how it could influence not only their health, but also their connection to and support of the natural world. The book spurred national dialogue about the importance of nature.

Ultimately, regardless of where you go along the river, and the park you choose to visit, you can find many ways to connect with the river: you can learn about the importance of plants, have a family picnic, go to a river festival or just take a walk. Our local parks can help you stay fit both physically and mentally while connecting with the river. So, if you are bored at home, go spend some time along the Raritan. See you out there!

Effective communication about the environment is critical to raising awareness and influencing the public’s response and concern about the environment. The course Environmental Communication (11:374:325), taught by Dr. Mary Nucci of the Department of Human Ecology at Rutgers University, focuses on improving student’s writing and speaking skills while introducing students to using communication as a tool for environmental change. Students not only spend time in class being exposed to content about environmental communication, but also meet with communicators from a range of local environmental organizations to understand the issues they face in communicating about the environment. In 2019, the course applied their knowledge to creating blogs for their “client,” the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP). Under the guidance of LRWP Founder, Dr. Heather Fenyk, students in the course researched topics about water quality and recreation along the Raritan. Throughout 2020 the LRWP will share student work on our website.

Fall 2019 Rutgers-LRWP course partnerships

As an all-volunteer organization, the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership benefits tremendously from student research and outreach contributions facilitated through partnerships with Rutgers, Middlesex County College, Raritan Valley Community College and other colleges and universities. Our student partners produce summary reports and research analyses, develop and deliver outreach material, shape policy guidance documents and more. They tell us that they love being able to do coursework that makes a difference. And several of our student partners have even won awards for their Raritan-focused projects!

Interested in applied coursework and research that benefits the Lower Raritan Watershed? Check out these Rutgers partner courses for Fall 2019:

Challenges and Opportunities in Environmental Planning: 11:573:409

Professor Heather Fenyk

Course Purpose: Environmental planning requires the integration of environmental information into the planning process and is concerned with the protection and enhancement of environmental systems while balancing demands for growth and development. This course considers big picture challenges and opportunities for integration of ecological services and social equity considerations into environmental planning at multiple scales.

Environmental History: 11:374:312

Professor Karen O’Neill

Course purpose: If you want to change how people use resources, you have to understand how those practices came about, how things could have been different, and how they might be changed through short-term or long-term work.

Environmental Communication: 11:374:325

Professor Mary Nucci

Course Purpose: Working with a local environmental organization, students will learn about issues in effective communication, and apply this knowledge to writing of materials to be used for public communication. By the end of the course, students will have improved communication skills that will help them compete for positions in the real world.

Theater for Social Development: 07:965:302

John Keller

Course purpose: Theater for Social Development is designed to develop

students understanding of how the arts can be integrated into community

development and engaged social interventions.

Media, Movements and Community Engagement: 04:567:445

Professor Todd Wolfson

Course purpose: This course will enable students to participate in the development of a journalism and media production project. They will also learn how to harness technology and study its implementation and impact on social change.

Mill Brook: Portrait of An Urban Stream

by LRWP Streamkeeper Susan Edmunds

Thirty years ago, my husband and I moved into a house down at the end of a quiet street in Highland Park. Beside the house, in a low area, ran a little stream, nameless as far as I knew. I imagined making a garden beside it until I saw the muddy water that rushed through after heavy rains, rooting out vegetation, clawing away at the stream banks, and depositing all manner of storm debris. I came to think of the stream as nothing but a source of problems. Years went by. I sought advice from various experts and made some progress in resolving some problems, though others remained.

Eventually, in the Rutgers Environmental Stewardship program, I learned that the problems of urban streams are predictable and can, at least in theory, be mitigated. I learned that, with active community involvement, even large rivers have been significantly restored. The RES program led me to the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and a plan to document the stream that I now knew was called Mill Brook.

I took pictures and made lists of storm sewer outfalls, eroded portions of stream banks, retaining walls in various states of disrepair, and multiple types of litter, wondering how this information about predictable problems might be useful. Increasingly, my attention was caught by the magnificently tall trees in the Mill Brook stream corridor, the bird song high above me, the calming gurgle of the water at my feet, and the sense of being far away while actually only a few yards from the hubbub of one of the most densely populated regions in the United States. I have learned that Mill Brook has been a source of much happiness for others, too, over the years.

I composed this Story Map Mill Brook: Portrait of an Urban Stream to invite you, the reader, to experience for yourself this valuable natural resource that runs like a ribbon through our community. I hope that a virtuous circle may arise in which the value of Mill Brook is acknowledged in our communities so that we willingly do what it takes to resolve problems created by developments that include our own homes. In return, Mill Brook will increase in value to us because it is a healthier natural resource and because we will have the satisfaction of caring for it.

Meet LRWP Board Member David Tulloch

Interview by TaeHo Lee, Rutgers Raritan Scholar

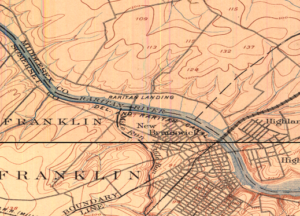

On the second Monday of 2019, LRWP Board Member and Rutgers Professor David Tulloch welcomed me to his office at the Center for Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis lab (CRSSA). Giant maps on the lab walls hint at what Professor Tulloch does at Rutgers. His research focuses on a mixture of landscape architecture and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Professor Tulloch received a Bachelor’s degree in Landscape Architecture at the University of Kentucky, his Master’s in Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University, and PhD in Land Resources at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He has now lived and worked in the Lower Raritan Watershed for two decades. He enjoys exploring our area on foot, urban hikes, and trying to connect pieces of landscapes that a lot of people overlook. These interests led him to create an interactive google map that explores various features of the Lower Raritan Watershed. The map will soon be a supplement for Professor Tulloch’s “Watershed Highlights and Hidden Streams: Walking Tours of the Lower Raritan Watershed,” which kicks off on Sunday March 16.

TaeHo Lee: Where are you from in the LRW, and in your time in the watershed, how have you engaged in/explored the watershed?

David Tulloch: I live in Highland Park near the Mill Brook, and I have lived there for nearly 20 years. I am within an easy walk to the Raritan making it hard to ignore the connection of the landscape and its watershed to the river. I’ve gotten to know the watershed as I explored it not only as a person who is curious about the large landscape. But also, as a benefit of my job, I have what amounts to two decades of mapping and design projects in different parts of the LRW and the larger Raritan River basin. Student research projects and studios have helped me get to know the watershed in ways that now are quite helpful in ways that, at the time, I didn’t always appreciate. My favorite thing to do in the Watershed is just to get out and walk it. I will look through historic maps or various air photos and look for hidden connections to explore. But there are also plenty of marked trails within the Watershed that I have yet to walk.

TL: As a parent, how do you want your kids to engage in/with the watershed?

DT: Well, I want my kids, like so many people who have grown up here, to really treasure this as a special landscape and see that it is both a special landscape and a singular, very large landscape. It has a fascinating history that we don’t talk enough about: American history, Revolutionary War, World War II, and an industrial history which is really significant as it impacted people around the world but also has impacted the river and our communities pretty dramatically. There are interesting educational and cultural histories for example, a colonial college right on the banks of the river in New Brunswick, the old proprietary house in Perth Amboy, the Monmouth Battlefield. So many things have marked this landscape. Additionally, its nature is incredible: Bald eagles, peregrine falcons, sandhill cranes, all within a few miles of us. And the landscapes that make up the Watershed are amazing: Mountains to marshes with really special spots within the Watershed like Duke Farms, Watchung Reservation, and the Rutgers Ecological Preserve. I really hope that my sons are coming to see the place not just as memorable but as incredibly special and something to treasure, even if they end up in another part of the world in the coming years.

TL. What, in your view, are the primary issues that need to be addressed in the watershed?

DT: The first for me is clearly the need to improve resident’s awareness of the Watershed and its issues, and their understanding of how both natural and policy processes within the Watershed work. I think one of the real challenges for us, an issue that affects ultimately the quality of water of the river, is encouraging our population of something like 800,000 residents to understand that the watershed is so much more than the river, and more than just the river valley. Most people associate the watershed with Donaldson Park, Johnson Park, Duke Island, or Duke Farms, and they can see those as areas that are associated with Raritan River. But we need to help them understand that in a 350 square mile watershed places like Freehold, Scotch Plains, and Bridgewater are all contributing to the water quality and the experiential quality of the watershed. And with a growing awareness and understanding, comes an appreciation of how much we still don’t know and how we need to enlarge our understanding of the river.

The other issue that really stands out to me is the land use of the watershed. It covers 350 square miles and includes 50 municipalities, each making their own independent decisions about land use with very little coordination, and we share collectively in the good and bad outcomes of these decisions. I live in one of those municipalities and work in another, but in between projects for work or taking my kids to different events I spend lots of time in other watershed towns experiencing the results of those independent decisions made in 50 different borough halls, city halls, and township halls. A really important step is to begin to monitor land use choices, and to examine them in terms of how they impact the watershed. We need to help the different people involved with the LRWP connect with those processes and see them in a more serious way.

TL. What is your vision for the LRWP?

DT: One important thing as a young organization, part of the shared vision we all have, is that as a growing organization it needs to be nimble enough to adjust to not only the changing needs of the Watershed but also the changing understanding of what the organization can become. Through listening and learning and reshaping itself, we all come to a new understanding of what the Lower Raritan Watershed as a community, as a physical landscape, and as a place with changing pressures on it, is.

Having said that, three areas are really important for us. One is appreciation. I don’t just mean that in the broadest sense, not just appreciating the place, but appreciation based on increased understanding. That’s getting more residents out on cleanups so they can see the problems themselves; getting as much as we can out of the research at Rutgers and the NJ DEP and from others working along the river so that our appreciation of those problems are also based on something serious.

Second is advocacy. My vision for LRWP sees it as a voice for the river and the Watershed that can really advocate for needs that often don’t have a strong voice.

Third is action. Turning the appreciation and advocacy into action. This includes small steps like cleanups, but some of the actions we take overtime can become more dramatic. Appreciation, advocacy and action, I think, together really represent a forward looking vision for the Watershed and the Partnership that could engage a very large number of residents and not just the usual suspects.

TL. You are a Professor at Rutgers. What is your role there? Can you provide insights into how we can best bring the resources and attention of the University to address the needs of the LRW?

DT: As a faculty member of Rutgers, I have formal roles. I am Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture, Associate Director at CRSSA, and lead the GeoHealth lab. A lot of the things that I do at Rutgers are as an integrator, as someone crossing over between different kinds of activities. So I work as an educator, and in landscape architecture I teach design, I teach planning, I teach what we call geomatics. But I’m also a researcher here at the center. We are looking a lot at the ways that the landscape is shaped and affects human health and our lives.

In my role as an integrator, I bring research into the classroom, and draw students back into the research. In the same way, I am now really interested in integrating the experiences with the watershed into the different activities that I have in Rutgers, as well. As part of my research 20 years ago or so, I visited and interviewed NGOs all over New Jersey, looking at their use of GIS and mapping. The groups that most caught my attention at the time were primarily watersheds. Many of them were brand new and in that way, for me, it was the first chance to learn and explore New Jersey’s landscapes. This forced me begin to confront the potential that Watershed organizations have as advocates for pieces of the landscape across municipal boundaries. I also began to see a role for integrating science and education and policy.

One of the other roles that I have at Rutgers is interacting with students. I get to know a lot of students as they first come to Rutgers. A role for me with students who are not from the area is helping them appreciate what a special place this is, getting them hooked on the River, and sharing Rutgers’ long relationship with the river. After all, it’s mentioned in the school song. In the broadest sense, to answer your question, we are so fortunate as a watershed organization to have a University like Rutgers in such an integral relationship with the river and the Watershed. But, with the many research and outreach programs that Rutgers has, one of my ongoing roles is going to be bridging the two and helping make connections with those activities and helping be a voice for the Watershed as well.

TL. I understand you are planning a series of “Walks in the Watershed.” Can you tell me more about this opportunity? What is your goal with the walks?

DT: Part of this goes back to simply trying to help all of us improve our appreciation and understanding of the watershed in little and big ways. But the walks are a very special way to connect the abstract places that we’ve all seen on maps with very real experiences on the ground. The goal with the “Watershed Highlights and Hidden Streams: Walking Tours of the Lower Raritan Watershed” is to help reveal connections across landscapes of the Watershed that are often hidden in plain sight, but also to help us explore some connections, like hidden streams, that are truly invisible.

Over time we will try some walks that explore the outer edges of the Watershed – Beyond the banks of the old Raritan – but at the start, we’re going to take walks that explore connections of important pieces of land to the river and, where possible, look into the streams that make those connections. So, one of the first walks, on March 17, is going to be close to the Rutgers campus here where we’ll be looking at the connections between Buell Brook and the Raritan by taking a walk that connects Johnson Park and some of its history and Raritan Landing with the Eco Preserve. Many people visit Rutgers’ Eco Preserve and don’t think, even when they are only hundreds of yards away from the river, don’t think of its connection to the river. The walks will look more at the connection and what it means. Walking also just reveals some other patterns and some hidden features along the way. I hope to be as surprised as the other participants. A second walk this Spring, scheduled for May 18, connects the old constructed landscapes of the canal at Duke Island County Park through a new greenway that has been developed along the Raritan and crosses over into the Duke Farms properties. I think a lot of the residents in that area are familiar with individual pieces. Fewer have made the walk to connect them all. We hope to make the walks a regular experience.

TL. Is there anything else you want to add?

DT: When you asked about what I do at Rutgers and how this helps make connections for the watershed, let me mention one more example. I think that as I teach planning students and geomatics students and design students who make some connection with the place, that the Watershed as a whole also is benefiting from those who stay here. An interesting example of that is Daryl Krasnuk, who I taught as an undergraduate student. Daryl has continued to volunteer and make maps both for the LRWP’s general education efforts and specifically for the State of the Lower Raritan Watershed report. It’s exciting to see the students that I taught now sharing their passion for this special place and finding ways to help up us to improve that landscape over time.

Protecting Darkness

As we move toward the shortest and darkest day of the year, and as the winter constellations take their places in our night sky, my family seeks out landscapes freed from the trespass of streetlights to check in with Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Perseus, Cassiopeia, Gemini, and Canis Major. These forays are times to marvel at the grandness of the universe, and give us pause to reflect on our place in it.

However, just like our terrestrial landscapes, even our views of the night sky need protecting. Did you know that fully 80% of the American population lives where they cannot see the Milky Way with the naked eye? Light pollution not only compromises our views of darkness and the heavens, it has implications for functioning of life on earth by changing bat and moth behavior, threatening rainforest regrowth, and contributing to the decline of firefly populations across the globe. Many towns around the world are adopting “Dark Sky Initiatives” to remind us that our lands and skies are interconnected, and that like our waterways and our forests, our dark skies need protecting.

It is the season of lights. Our houses and streets are glowing with color. We string the Christmas trees with miniature glowing orbs, set out the diya, and light the candle in the Menorah. The visual display is joyous, festive, welcoming and wonderful. But consider adding a new tradition to your holiday calendar: turn off your lights and go out to gaze at the brilliance of the winter sky.

My family will do just that during our annual visit to Rutgers’ Serin Observatory during “Public Open Nights.” There we observe the night sky through the 20-inch optical telescope. Barring inclement weather, on December 13, 20 and 27 the (unheated) observatory will be open for two hours starting at 8:30 p.m. We are hoping for clear views of M31, Almach, NGC 457, h & χ Persei, η Persei, M45, M42, Betelgeuse, Sirius, Neptune-Mars appulse, Uranus, and the Moon.

As we scan the skies and take in the vastness of things, remember to take stock of your power to affect positive change in the here and now. Even in urban light polluted areas like the Lower Raritan Watershed there are things we can do to save the stars:

- Light only what you need

- Use energy efficient bulbs and only as bright as you need

- Shield lights and direct them down

- Only use light when you need it

- Choose warm white light bulbs.

Happy Holidays!

Stream Habitat Assessment of Ambrose Brook – 10 October 2018

Article and Photos by Margo Persin, Rutgers Environmental Steward

Editor’s Note: In 2018 Margo Persin joined the Rutgers Environmental Steward program for training in the important environmental issues affecting New Jersey. Program participants are trained to tackle local environmental problems through a service project. As part of Margo’s service project she chose to conduct assessments of a local stream for a year, and to provide the data she gathered to the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP). Margo keeps a journal of her experiences, excerpts of which are included in the LRWP’s “Voices of the Watershed” column.

This visit to the Ambrose Brook in Middlesex, NJ took place on a sunny, blustery fully autumn day. I didn’t know what to expect in regard to this visit, given that Hurricane Michael had blown through NJ the previous day. What was most impressive about the site was that it was imbued with a sense of energy and even restlessness, perhaps a carryover from the weather event of the day before. As I wandered along the stream bank, my attention was caught by the wind, strong gusts that kicked up dust and a trail of early falling leaves that scattered along the footpaths, the banks of the moving brook, and settled momentarily on the water. There was plentiful sunshine, open blue sky, a few scattered clouds that gave scant shadow on the earth, but… fall is in the air. The surrounding trees have not yet lost all of their leaves, but it is evident that the summer heat and earth’s natural cycle are performing their annual duty: the tree color is washed out, leaves are drying out and there is more space between the upper branches, as evidence of the drying and falling leaves. The tall grasses at various points on the stream banks have taken on a brownish hue, in contrast with the deeper green of the earlier summer months. Is there a change in the sunlight’s power? I tend to think so. In resting for a few moments on the banks of the stream on a strategically placed bench, I noted that the angle of the sunlight was lower, so the sun’s rays and warmth were mitigated by the obvious change of season, the rotation and tilting of our green planet here in the northern latitude toward winter. Oh, don’t utter the word!

The restlessness that I noted previously can be attributed to the energy that is expressed in the pulsing of the planet via various sources: the movement of the wind, as noted in the trees, grasses and leaves, the rustling and creaking of overhead branches, and the comings and goings of the Canadian geese. For this visit, various groups of geese appeared to be organized into elite squadrons, squawking their arrivals and departures on clearly defined areas of the brook, which took on the function of an aquatic airport, an avian Newark Liberty, as it were. None were to be found on the grass or footpaths. In contrast with earlier visits during spring and summer; for this visit, the geese were supremely active, aggressive even, as if protecting given areas on the water’s surface for their landings and take-offs. I wonder if their ancient memory of paths of fall migration was contributing to their agitation. Their honking and hissing carried from all along the footpath. Other birds that were noted were hearty and intrepid blue jays, who with their size and weight, seemed to be able to tolerate the wind’s gusts and buffeting, as well as a privacy seeking blue heron. The latter was tucked into a quiet shallow at the base and to the side of the waterfall, likely an attempt to avoid and ignore the noisy Canadian geese. (This last comment is a glaring example of anthropomorphism, I know, but those geese really are quite vocal, pushy and …mildly annoying.) Ground squirrels, who appear to be in fine flesh, have begun to heed autumn’s warning, several were observed collecting and munching on the first fall of acorns from the surrounding oaks.

Ambrose Brook was swollen and fast moving, manifesting a steady and plentiful flow, with even some white water at the base of the waterfall. Although I had not brought any measuring equipment for this visit, my ‘guess-timate’ based on visual measurement alone as to water depth was approximately 8-10 inches closer to the bank and 12-15 inches toward the center of the stream and past the small waterfall, surely because of the rainfall from Hurricane Michael. The stream had lots of surface ripples, which acted as prisms for the sunlight, and thus produced a dancing refraction of water, waves, and light. Lovely.

So, this cycle of observation and assessment of mine will soon be drawing to a close. My commitment was for a year’s worth of visits and measurements. Given that I began in December of 2017, only a few more visits remain. Now that autumn is upon us, I am struck by the wholesomeness of this process and how the observation of nature’s constant change ironically demonstrates its sureness and constancy. The beauty of each season does not depend on human intervention – nature and the environment are enough, in and of themselves.

Summer Solstice Stream Habitat Assessment of Ambrose Brook

Article and Photos by Margo Persin, Rutgers Environmental Steward

Internship Diary / June, 2018

So summer is in full swing – I made a visit to the Ambrose Brook immediately after the summer solstice, on 24 June 2018. The environs have changed in several ways, both passive and active. There are several aerating fountains that spray a cool mist that is distributed by the shifting breezes off the water. The highwater mark on the center island has changed since I last visited, probably because of late spring run-off. But the water has even been higher, as evidenced by the residue on all of the banks, the tree roots that extend into the water, and the low-lying bushes. All are wearing a dusty mud color that gives evidence of water that has since receded. Water flow has significantly strengthened, as is noticeable over the modest waterfall close to Rte. 28. In addition, the rain run-off in the two drains has increased, so that more than a trickle from both of them is observable as it enters the brook after the waterfall.

Fauna have increased. One of my prize observations was that of a somewhat lazy or perhaps sleepy but wary blue heron standing on just one leg somewhat in the middle of the stream, past the waterfall. I tried to ease my way in a stealthy and languorous manner along the bank to not call attention to myself, but alas, the heron quickly reacted to my not so subtle approach, was on to me as I slowly worked my way toward the lovely bird . S/he dropped the second leg into the water, turned a cold shoulder in my direction, then deliberately moved away from where I had planted myself on the bank opposite to his/her position. Even though the distance between us stayed about the same, I was so taken by the proximity of this lovely creature and my ability to observe without causing a startled reaction. S/he continued a slow and deliberate saunter down the creek and disappeared around the bend. What a treat to be able to be a silent observer of a stream visitor. Nice!

I also noted that the population of Canadian geese has multiplied to a startling extent. And the birds have become so accustomed to human presence that they barely move when a vertical mammal saunters among them, even when they are settled down and roosting on the grass, the available paths or the cement. In order not to encourage their presence, the township has placed signs that pointedly give the command NOT to feed the waterfowl. Obviously, they greatly outnumber any other visitors to this place, either animal or human. And needless to say, mementos and tokens of their presence are all around, some pleasant and others not so much. An addition to the command to not feed the waterfowl would be “Watch your step and be sure to check your shoes before getting in your vehicle.”

Another observation is that butterflies and moths inhabit the environs, with several Monarchs making their graceful presence known as they fluttered past and through my line of vision. Their wingbeats cast a silent beat to the pulse of the planet as they made their way over and through the environs.

Human presence has also increased. It should be noted that the four walkways that run over and parallel to the stream offer an unobstructed view. And all of them are handicap accessible either all or in part. In other words, on all of them ramps are available so that proximity to the stream can be achieved. People who are fishing on the walkways are only part of the traffic. There were several runners, families with tots and strollers, and other quiet observers to finish out the panorama. My next visit in July will be for another stream assessment, boots, thermometer, floating duck, ruler at the ready Happy summer, everyone!

Protecting the Rutgers Ecological Preserve

Article and photos by Daniel Cohen, Rutgers University junior

As a lifelong resident of Highland Park, and currently a student at Rutgers I have greatly enjoyed hiking throughout the university’s Ecological Preserve, a relatively pristine area located on the Livingston Campus. The Rutgers Preserve was established in 1976 as an ecological resource. Its purpose is to serve as an aesthetic, educational, and recreational area for the Rutgers community as well as for the residents of New Jersey. This 360-acre Eco-Preserve is the habitat of numerous creatures including migrant songbirds (warblers and towhees). It is also the home of the white-tailed deer. The Preserve is the site of native plants such as Spring Ephemerals and Jack-in-the-Pulpit, as well as Ash, Beech, Hickory, and Red Oak trees.

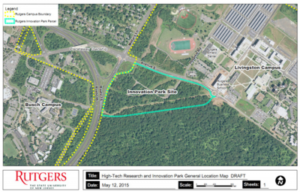

Anyone concerned with environmental matters in the Lower Raritan Watershed should be aware of the proposed Rutgers “Innovation Park” (IP) plan – an infrastructure project to be constructed adjacent to the Rutgers Eco-Preserve site. Rutgers has requested that the New Jersey Commission of Budgeting and Planning allocate $4.75 billion for infrastructure projects on its campuses as part of a Master Plan. Included in this proposal is funding for IP, a major project to be built on the edge of the Preserve. According to the Rutgers publication Business Plan and Implementation Strategy (2016), its purpose is to “promote research collaborations, technology transfer and commercialization, job creation, and public-private partnerships.” IP, an inter-disciplinary learning site with a goal of furthering environmentalism is well-intentioned.

However, a project whose mission is environmental may nevertheless be harmful to the Preserve’s ecosystem. A major building project occurring just outside the Eco Preserve’s borders may well threaten fauna and flora within the Preserve itself. The project will result in pollutants from trucks and construction machinery as well as in greater noise levels. Fossil fuel emissions, the primary cause of climate change, have already caused the destruction of species of animals and plants worldwide. Excessive construction noise is harmful to the well-being of animals and plants as fossil fuel emissions and increased decibel levels will not stop at the Preserve’s periphery. The essential question is to what degree, the site will be impacted.

If it has not yet done so, Rutgers must conduct a thorough environmental review of the effects of this infrastructure project. Although in the Rutgers publication there is an environmental assessment of the IP site itself, there is no reference to its impact on the adjacent Eco-Preserve. There should be a comprehensive environmental assessment regarding how the IP project will impact this area. Residents of Central New Jersey and beyond, including members of the Rutgers community who care about protecting this vital habitat, must be given the opportunity to interact with those involved with this project.