The LRWP is pleased to be part of Jersey Water Works, a collaborative effort of many diverse organizations and individuals who embrace the common purpose of transforming New Jersey’s inadequate water infrastructure by investing in sustainable, cost-effective solutions that provide communities with clean water and waterways; healthier, safer neighborhoods; local jobs; flood and climate resilience; and economic growth. The LRWP is active on the Green Infrastructure subcommittee.

Jersey Water Works recently published Our Water Transformed: An Action Agenda for New Jersey’s Water Infrastructure – check it out! And plan to join Jersey Water Works for their annual conference on December 7 at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark!

Article by LRWP intern Daniel Cohen

The Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) is looking for volunteer weather observers in the Raritan Basin. CoCoRaHS is a nationwide volunteer precipitation-observing network, with over 15,000 active observers in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, Canada, the Bahamas, and the US Virgin Islands, including over 250 in New Jersey. The NJ program is run out of the Office of the NJ State Climatologist at Rutgers University. Working with the Rutgers Sustainable Raritan River Initiative, NJ CoCoRaHS is looking to enlist volunteers of all ages within the basin. Volunteers take a few minutes each day to report the amount of rain or snow that has fallen in their backyards. All that is required to participate is a 4″ diameter plastic rain gauge, a ruler to measure snow, a computer or cell phone, and most importantly, the desire to report weather conditions.

Observations from CoCoRaHS volunteers are widely used by scientists and agencies whose decisions depend on timely and high-quality precipitation data. For example, hydrologists and meteorologists use the data to warn about the potential impacts of flood and drought within the Raritan Basin.

“Weather matters to everybody –meteorologists, car and crop insurance companies, outdoor enthusiasts and homeowners,” according to CoCoRaHS founder and national director Nolan Doesken. “Precipitation is perhaps the most important, but also the most highly variable element of our climate.”

As Dave Robinson, NJ State Climatologist and NJ CoCoRaHS co-coordinator, notes, “The addition of new observers in your community will provide a detailed picture of rain and snowfall patterns to assist with critical weather-related decision making.”

“Rainfall amounts vary from one street to the next,” says Doesken. “It is wonderful having large numbers of enthusiastic volunteers and literally thousands of rain gauges to help track storms. We learn something new every day, and every volunteer makes a significant scientific contribution.”

CoCoRaHS volunteers are asked to read their rain gauge or measure any snowfall at the same time each day (preferably between 5 and 9 AM). Measurements are then entered by the observer on the CoCoRaHS website where they can be viewed in tables and maps. Training is provided for CoCoRaHS observers, either through online training modules, or preferably in group training sessions that are held at different locations around NJ.

“Anyone interested in signing up or learning more about the program can visit the CoCoRaHS website at http://www.cocorahs.org,” says Mathieu Gerbush, Assistant NJ State Climatologist and program co-coordinator. “We’re looking forward to welcoming new volunteers into the NJ CoCoRaHS program.”

For more information, contact the NJ CoCoRaHS state coordinators:

Dr. David Robinson, Rutgers University, drobins@rci.rutgers.edu, 848-445-4741

Mr. Mathieu Gerbush, Rutgers University, njcocorahs@climate.rutgers.edu, 848-445-3076

By Heather Fenyk, LRWP President and Founder

We are just a few days shy of July 1, 2018, which marks the 35th anniversary of the Clean Water Act’s failure to meet it’s “fishable-swimable” goals for our nation’s waters. What does this mean for New Jersey’s waters? The most recent published report (2014) on New Jersey’s water quality tells us that only 16% of our waters fully support general aquatic life. That is, the vast majority of our waterways are not clean enough for drinking water, aquatic life, fish consumption, or even recreation.

The Clean Water Act was about more than the protection of recreation, and fish and wildlife propagation. It was an “interim goal of water quality” intended to lead to “fishable and swimmable” waters by July 1, 1983, and to “the national goal that the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters be eliminated by 1985.” But more than a third of a century later the quality of our waterways, especially waters in our urban and historically impacted areas, are far from meeting fishable and swimmable goals.

Why? Because existing laws don’t ban pollution. They allow for polluters and developers to secure permits to pollute. The Clean Water Act is especially weak in terms of regulating the number one source of pollution in our national (and notably our New Jersey) waterways: stormwater.

Urban non-profit environmental organizations, like the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership that I run, go about the daily work of advocating for local watershed management strategies like stormwater utilities and Green Infrastructure to address the water quality and quantity problems in our watersheds. And state-wide collaborative efforts like Jersey Water Works are making tremendous strides to transform New Jersey’s water and wastewater treatment and delivery infrastructure. But without a wholesale shift in thinking around pollution in our waterways, our local waters will never meet the “fishable, swimmable” goals as set out by the CWA, no matter how many Combined Sewers we take off line, or how many rain barrels and rain gardens we install.

What else should be on our radar? How should we be rethinking water pollution policy in New Jersey? On the anniversary of the 35th year of the failure of the CWA to meet it’s goals, we offer you our top 10 ideas for effective change:

- Fund major research and development for innovative water treatment and water quality monitoring technologies;

- Offer economic incentives to polluters who perform beyond the minimum requirements of the law;

- Add public health objectives to our water pollution control laws;

- Prioritize clean-up and restoration of polluted waterways, especially in our economically disadvantaged communities;

- Establish new target dates for achieving fishable, swimmable waters in New Jersey;

- Establish target dates for completely eliminating the discharge of pollutants in our waterways;

- Develop real-time monitoring technologies that protect water consumers and recreational users;

- Increase enforcement of existing laws;

- Establish mandatory monitoring for emerging pollutants including micro-plastics, pharmaceuticals and hormones;

- Develop a central repository for information and resource sharing on best management practices in the state.

We welcome comments, additions and suggestions. Email us to share yours: info@lowerraritanwatershed.org

Active CSO Discharge, Perth Amboy – photo credit: Raritan Riverkeeper Bill Schultz

By Arianna Illa, Coordinator, Civic Engagement and Experiential Learning, Middlesex County College

The Watershed Sculpture Project: Middlesex County College

On Tuesday, November 21st of last year, students enrolled in Integrated Reading and Writing (ENG 096) at Middlesex County College (MCC) did something unusual for a typical college course. Rather than meeting in their classroom, they boarded a college van to travel to the Fox Road underpass, a stretch of road off the highway in Edison, NJ. This class excursion was the culminating event following a semester focused on reading, writing, discussing, and learning about environmental issues faced by local communities. In collaboration with the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP) and the Edison Environmental Commission, students planned and executed a community cleanup service project as part of the greater service learning initiative happening at the College.

Students Jessica Colon or Rahway (left) places trash in the bag held by Carolyn Muncibay of Old Bridge.

The cleanup involved spending 3 hours of class time bagging trash and recyclables along the underpass. The location of the cleanup was especially significant as it is uphill from the Raritan River. When it rains, trash and other contaminants travel downhill, further polluting the already vulnerable river. By the end of the cleanup, 17 bags of trash and recyclables, nine tires, a suitcase, car seats, as well as other large trash items were collected.

John Keller, Director of Education and Outreach of CoLAB Arts, assists students during the hand sculpture creation process.

During the cleanup, students selected one small trash item to bring back to campus. In collaboration with local arts advocacy organization CoLAB Arts, students created cement hand sculptures which are now on display in the MCC College Center in an exhibition titled The Watershed Sculpture Project: Middlesex County College. Each sculpture is of a student’s hand holding the trash item they saved from the cleanup.

The display demonstrates the large impact seemingly “small” amounts of littering can have on the environment as a whole, and likewise demonstrates the power of simple acts of stewardship (including stream clean-ups and socially engaged art) to effect positive environmental change. This work seeks to raise awareness of issues of environmental damage happening in the local community, and to prompts viewers to examine and reflect on their own relationship and interactions with the environment.

If your non-profit organization is interested in getting involved with service learning at MCC, please contact Arianna Illa, Coordinator of Civic Engagement and Experiential Learning, at ailla@middlesexcc.edu.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Rose gets a green aluminum band affixed to her left leg and a silver band to her right leg. Green is the band color used by NJ and silver is a federal band. Each state uses a specific color to quickly identify a banded eagle’s origin.

Over last century as the northeast bald eagle population dwindled, their image flourished as a marketing tool to brand high end merchandise. Gilded eagles sat upon flag poles in parades and auditoriums. Dollar bills and quarters bore engraved, lone eagles, wings spread and talons flared, about to attack at the least provocation.

Never did any image show more than one eagle, even though they mate for life and are dedicated parents. As a generation, we came to know eagles as powerful solitary creatures frozen in iconic poses. There was nothing to challenge that image, the skies were empty and no shadows could be seen speeding across the land. Least of all in central NJ, a land reputed to be sanitized of nature.

Awareness of man’s place in the natural world and his impact on the environment began to be studied in universities like Rutgers College of Agriculture and Environmental Science in the late 1960s, which opened the door to a new era of enlightenment and activism. Books like Silent Spring and Sand County Almanac were the seeds sown to nourish the idea humans were not apart from the cascade of life that flowed, uninterrupted, from the soil and water to apex predators, like the eagle and peregrine falcon.

Eagle restoration in NJ began in earnest in the 1980s accompanied by an ever-growing accumulation of study data gleaned by observation and scientific research. Still the view of intimate eagle relationships and social interaction remained at a sky-high level and not well published for public consumption.

Eagles kept their privacy and legacy reputation as solitary creatures intact until the advent of live cameras, genetic mapping, banding and miniature transmitters.

As far as the public is concerned, it is the live cams, set above some nests and broadcast on the internet, that provide non-stop coverage of eagle antics in the aerie to feed an insatiable voyeuristic human appetite.

The forums that accompany these spy cams generate lively conversation and together, have created a whole new audience beyond those immersed in all things nature. People who can’t tell a snow goose from a snow bunting, are now addicted a wildlife reality show.

And addictive it is, as viewers and scientists both learn what goes on behind nest walls. As voyeurs watch, they see behaviors that mimic human responses. The eagle screaming at its partner could very well be a replay of last night’s argument with their spouse, “who never listens to a word I say”.

Cumulatively, what we see are personality differences among pairs of eagles, where before we had only anecdotal observations and generalized conclusions. We knew the eagle as a solitary warrior and now we see a great raptor dedicated to its mate and offspring. When we look closely into the world of an eagle we see a glimpse of ourselves.

Locally the intrigue has been riveting, with a ringside seat to a female ingénue coming between a mated pair, a harassing hawk obliterated by an annoyed eagle and tender moments of dedicated parents doting on their precious offspring.

We watch as courting behavior evolves into mating, egg laying and alternate job sharing, as pairs relieve each other from brooding duty. We see and hear the wailing of one parent when their mate fails to return, either through injury or death. You cannot be unaffected by that sight and sound as what you experience is automatically translated into human terms.

A live cam from another state showed a female eagle covering her three, day old chicks, as a late spring snowstorm raged. That moment was tender enough but then the male positioned himself alongside the female, resting his head on her shoulder and spread his wings to shield his mate and their chicks from the heavy snowfall; our collective tears flowed.

Recently an eagle that prematurely fell from a local nest was rescued, examined and found to be in good health. Given that one parent went missing in the weeks prior to the fall and it was impossible to return the bird to the nest, a decision was made to place that eagle in another nearby nest.

Armed with the knowledge of intimate eagle behavior and demonstrated dedication to their young, fostering that young eagle was done with full confidence it would be accepted and thrive.

Only time will tell but so far, so good. Years hence, if you see a bald eagle bearing a green leg band, engraved with E68, you now know the rest of the story. Consider an eagle that was killed, June 2015, in upstate NY by a car, was banded 38 years prior! So, eagle E68, affectionately named, Rose, and her foster siblings, E66 and E67 have a good chance to be seen by your grandchildren!

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

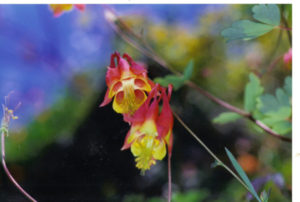

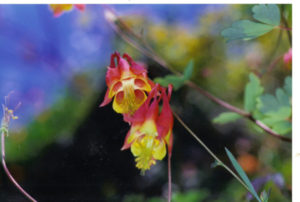

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Looking up into the columbine flower’s mouth, I see a dove with wings spread or an angel. This diminutive wild flower is found in isolated patches among the red shale cliffs that line the South Branch. Who knew, other than hummingbirds, that such a treasured crown jewel was hidden along our river.

The red shale cliffs interrupt pasture and field along the South Branch to stand as an unchanging reference point, immune to progress and raging spring floods that swirl around them.

The exposed cliff face is characterized by a jagged appearance, with sections of smooth rock face the exception. Ancient floods have scoured rounded contours into the soft shale, to form shallow caves, nooks, crannies and alcoves. Like a human face with striking character, the cliffs beg more than a casual glance.

I cannot paddle by without desperately searching the high cliff face for ancient etchings or a petroglyph. Travelers from earliest times could not have passed up an opportunity to scribe their name or draw their hunting or fishing trophies into the smoother areas of these red shale sketchpads. It would be against human nature to leave no sign.

Unexpectedly, what I have found among the craggy shale cliffs is a species of native wildflower that begins to bloom in late April through May. Wild columbine is not found anywhere else, except in the crevices of the prominent shale outcroppings along the river.

Columbine is a finely structured red and yellow flower, in the shape of a crown with five distinct tubular projections. The openings of the five separate passages are shrouded in a common vestibule. Several stalks arise from one clump, one flower to a stem, opening faces downward. The plant is not found in profusion, just in scattered, isolated patches.

There are many commercial cultivars and species of columbine, so to be clear, the wild native columbine is Aquilegia columbine. The derivative of the name is interesting as, ‘Aquila’, is Latin for eagle, and columbine references the family designation of doves. Early taxonomists saw characteristics of both in the flower. It is said the ‘spurs’ resemble the open talons of a raptor and the face of the flower, a nest of doves. To me the spurs that project to form the crown remind me of the reversed leg joint of a grasshopper when viewed from a certain angle and looking up into the mouth of the flower, I see the form of a single dove with wings spread.

The columbine flower produces tiny round black seeds in late May that are indistinguishable from poppy seeds. Though the columbine blooms about the time the first migrating hummingbirds show up, I have yet to catch a hummer dining on the flowers but surely some returning hummers have the plants marked on their GPS.

How and when columbine first found anchorage in these cliffs is a mystery. In the absence of its known origins, I prefer to think of these flowers as inheritance from an ancient legacy of primitive plants. The first of which relied on wind for propagation and then, as if by the hand of an engineer, designed shape, color and form to take advantage of insect pollinators and local soil conditions. Could it be that flowers intelligently made use of the cliffs to mark their presence through the centuries where humans left no trace?

Wild columbine are the crown jewels hidden among the cliffs, that appear in the spring for a brief moment to enrich both pollinators and humans who stumble upon them.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

A hummingbird and orange trumpet flower engage in an evolutionary dance of equal partnership that has lasted for eons. The flower not only took advantage of an array of pollinators but also stole the heart of man who would seek to propagate flowers far beyond their natural range and ability to survive.

A name logically follows the existence of an idea, a person, place or a thing and forever provides an instant reference, complete with assigned identifiable characteristics. So before there was a month named May, a segment of time existed in nature where birth and bloom dominated the season.

The mythology from which the name of May arose was based on the same natural observations seen today. Stories of the stars and the gods became the reference points displayed on the night sky overhead projector to help explain observed phenomenon. The poetic phrase, “April showers bring May flowers” provides information sufficient enough for most people to understand the season. Instead of placing flowers at the altar of the goddess Maia we now send flowers to our mothers on a day designated to show her our appreciation, same story, different day.

Going back to the time before May, can you imagine discovering the first flower ever to bloom? In retrospect it would have meant that some plant had evolved to take advantage of a new method of pollination that relied on insects rather than wind. At the time of discovery, however, the moment had to be absolutely magical. Here was something so different in structure, color, scent and profusion that it instantly intensified a fledgling human emotion that speaks to the appreciation of beauty. The flower not only took advantage of insect pollinators but at that moment stole the heart of man who would later seek to propagate flowers far beyond their natural range and ability to survive.

Watching a rambunctious fox pup at a distance, I saw what appeared to be orange pollen on its solid black nose. As the pup was playing around the daylilies I imagined he stuck his nose inside a funnel shaped orange flower, designed for bees and hummingbirds, to come away with the telltale signs of brightly colored pollen grains. If he sniffed a few more flowers he actually became the “bee” and a willing, if not random, participant in asexual reproduction. The part that serendipity plays in nature and science can never be underestimated and its potential never unappreciated when unprecedented success results.

Fox pups are not the only pollinators unknowingly pressed into service by the ingenious evolutionary design of flowers. It is a laugh riot, for some reason, to see a dusting of yellow or orange pollen on the nose of a child or adult who sniffs a flower in pursuit of its scent. Eyes closed, as if about to plant a kiss, the human pollinator presses forward until nose touches stamen.

The entire event, so instinctive and innocently conducted, that the “bee” comes away unaware of its role in the evolutionary drama of species reproduction and survival. A kind friend will of course bring attention to the dusting of pollen left by such an intimate encounter and be trusted to address it discreetly.

Bees of all kind have ‘pollen baskets’ on their back legs which hold an accumulation of pollen grains that appear as large colorful round beads on opposite back legs. Watch one of those big furry yellow and black bees and you can easily see the lumps of colorful pollen that varies from flower to flower.

Paddling along the south branch, wild columbine can now be seen in select places on north and west facing red shale cliffs. These delicate plants grow from roots wedged between the layered red shale well above the surface of the water. The reddish pink tubular flowers with a common yellow center resemble a group of ice cream cones joined to form a common opening which leads to several individual tails. This structure encourages contact with the centrally located pollen that has to be brushed against in order to reach several sources of nectar located in each tail. This flower must have had a hummingbird sitting on the design team who decided not only the flowers structure but the time the flower was set to bloom. Hummers arriving in early spring from Mexico and Central America have a ready source of food to replenish the energy spent in their annual migration north.

Consider the greatest mayflower of all and the part it played in another notable migration. The “Mayflower”, was a ship that sailed to our shores bearing its human pollen to establish new life on the North American continent The ship, so named by unknown whimsy and intended as a supply barge, grew to evolve much as early flowers did into an effective delivery system directed by nothing more than chance. Like a flower it bloomed, spread its pollen and ‘died back’ soon after returning to England.

May apples, Virginia bluebells, trout lilies, trillium, jack-in-the pulpits and spring beauties are a small sample of local May flowers that represent the spectrum of a floral legacy whose genealogy traces back to the earliest flowers. Consider that flowers are living things that in some magical way recruited man to further their propagation in exchange for a glimpse of eternal beauty, dreams and imagination to expand the universe of human potential with unbounded creativity and expression.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Sapia

Matchaponix Brook near Englishtown Market in Manalapan, Monmouth County. This section of the brook is both diamond and rough — a beautiful natural world fighting the nonpoint-source pollution along Route 527. Brook in the foreground, swamp hardwood forest in the near background, and in the left of the far background, pitch pine trees of the Spotswood Outlier, disconnected from the main section of the Pine Barrens to the south.

MATCHAPONIX BROOK AT ROUTE 527: I am 61-years-old and have been crossing Matchaponix Brook at Englishtown Market in Manalapan, Monmouth County, since as far back as I can remember. Yet I never gave much thought to the natural world here — until Englishtown outdoorsman Gary Forman relayed information to me through our mutual friend, outdoorsman Frank Ulatowski. This is the beginning of Matchaponix Brook, formed by the joining of Weamaconk Creek and McGellairds Brook. When I stopped by this week, I was amazed. Step only a few feet away from busy Route 527 and one is in a beautiful natural world of brook; swamp hardwood forest; a lodge of beaver, “Castor canadensis”; mallards, “Anas platyrhynchos”; great blue heron, “Ardea herodias”; and the telltale pitch pine, “Pinus rigida,” of the Pine Barrens because this is part of the Pines’s disconnected Spotswood Outlier. Probably plenty more that I did not notice. Unfortunately, I did notice the nonpoint-source pollution — garbage gathering in Matchaponix Brook. Take away this garbage and the busyness of Route 527 and I was in a wonderful natural world. Again, we should keep our eyes open because the natural world is around us, even if we taint it.

A great blue heron on Matchaponix Brook in Manalapan, Monmouth County.

AS BEAUTIFUL AS MATCHAPONIX BROOK IS AT ROUTE 527…: Nonpoint-source pollution — basically debris, such as litter or materials blown offsite, with no specific origin — is a major problem in our world. Simply look at litter along a road or, in this case, gathered in Matchaponix Brook at Route 527 in Manalapan, Monmouth County. Generally, the source of this garbage appears to be debris that drains into the brook and Route 527 littering.

Garbage in Matchaponix Brook at Route 527 in Manalapan, Monmouth County.

Garbage in Matchaponix Brook at Route 527 in Manalapan, Monmouth County.

MATCHAPONIX BROOK: In the Englishtown area of Monmouth County, Weamaconk Creek and McGellairds Brook join to form Matchaponix Brook. The brook then flows for about 5 miles, as the crow flies, to the north and merges with Manalapan Brook to form the South River on the boundary of Monroe, Spotswood, and Old Bridge in Middlesex County. “Matchaponix” is a Lenni Lenape Indian word for “land of bad bread,” or land where corn does not grow well. I speculate this name comes from the Matchaponix Brook area being in the Spotswood Outlier of the Pine Barrens, or an area of sandy soil not conducive to growing corn or other conventional crops. (Conversely, “Manalapan” means “land of good bread.” Manalapan Brook begins and runs for miles in a non-Pine Barrens area, or an area of darker, gravelly soil that is good for growing corn.)

Mallards on Matchaponix Brook in Manalapan, Monmouth County.

SPRING SPRINGING: People are fishing. Listen in the early morning and you will likely hear birds singing. Look at a woods and you likely will see the red buds of trees. Flowers are blooming in gardens. Nature is coming alive with spring.

Warren Kiesler churns up horseradish plants on his farm in Cranbury, Middlesex County. To the right of the tractor in the background, notice the tree budding.

An angler at “Jamesburg Lake’ (properly “Lake Manalapan”) on the boundary of Jamesburg and Monroe, Middlesex County.

ROBINS IN THE YARD: With the coming of spring-like weather, it means the likelihood of seeing robins, “Turdus migratorius,” in our yards. I have noticed more of them around my yard in Monroe, Middlesex County. This week, I watched a robin pull a worm from my garden. “Although robins are considered harbingers of spring, many American Robins spend the whole winter in their breeding range,” according to Cornell University’s All About Birds website. “But because they spend more time roosting in trees and less time in your yard, you’re much less likely to see them.” As the weather warms and nature comes alive, they move to yards because of the availability of such things as worms. “American Robins are common sights on lawns across North America, where you often see them tugging earthworms out of the ground,” according to the Cornell website.

A robin in the shrubs of my front yard in Monroe, Middlesex County.

HORSERADISH FARMING: With the collapse of newspapers and, in turn, the collapse of my approximately 35 years as a reporter – basically from 21-years-old when I got my journalism degree to 55-years-old – I am always looking for work. Over those 5-plus years, I have been a part-time staff writer on a weekly paper, freelance writer, writing teacher, security guard. Security guarding, which I did during my college years and resumed these years later, now takes me from a Central Jersey professional park to the perimeter around foreign cargo ships where Maryland’s Patapsco River meets Chesapeake Bay. As I like to say, I have the best syntax at the Baltimore docks and am the only employee of Rutgers University’s Plangere Writing Center that wears a hard hat on his other job. This week, at 61-years-old, add laborer at the Kiesler horseradish farm to my resume.

Harvested horseradish on Kiesler farm in Cranbury, Middlesex County.

SNOWBIRDS GOING, GOING…: When will “snowbirds” — juncos, “Junco hyemalis” — be gone for the season? Based on field notes I have kept over the years, they should be leaving Monroe, Middlesex County, any day now to about April 25 or so. They will head to high ground, as close as North Jersey or Pennsylvania or as far as Canada. Then, I will see them again around the yard about mid-October to early November.

Manalapan Brook in the section of Monroe between Helmetta and Jamesburg, Middlesex County.

IN MY GARDEN: I finished the planting of the early spring crop — Kaleidoscope Blend Carrots, Touchon Heirloom Carrots, Bloomsdale Long-Standing Heirloom Spinach, Early Wonder Heirloom Beets, and Salad Bowl Lettuce, all Burpee products.

I found this in my garden. Something got this bird, the remains possible those of a mockingbird, “Mimus polyglottos.”

YARDWORK: I tackled the first yardwork of the season, working the front yard. I trimmed trees and prepared soil to plant zinnia and warm-season vegetables. The latter is a continuation of my plan to make my one-quarter-acre yard as productive as possible. With that idea, I am trying to minimize a generally unproductive lawn as much as possible.

PRINCETON ENVIRONMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL: I attended the annual Princeton Envirionmental Film Festival, seeing part of the “Evolution of Organic” movie and the entire “Seed to Seed” movie, both about organic farming. I also got to see the talk of Dr. Joe Heckman — organic farmer, a member of the board of directors of Northeast Organic Farming Association of New Jersey, and Rutgers University soil scientist — after the showing of the “Evolution of Organic” and got to socialize with Joe. (Joe and his wife, Joyce Goletz Heckman, own Neshanic Pastures farm in East Amwell, Hunterdon County. Joyce and I are childhood friends from Monroe, Middlesex County.)

Awaiting a movie at the Princeton Environmental Film Festival.

Dr. Joe Heckman, who spoke on organic farming at the Princeton Environmental Film Festival. Joe is an organic farmer, a member of the board of directors of Northeast Organic Farming Association of New Jersey, and Rutgers University soil scientist.

UPPER MILLSTONE RIVER EAGLES: We are pretty sure the nest of bald eagles, “Haliaeetus leucocephalus,” on the Upper Millstone River on the boundary of Mercer and Middlesex counties, has one eaglet in it. The baby should fledge in early to mid-May or the early end to early June on the far end. Then, the family should stay together in the area. After fledging, the young eagle or eagles should stay in the area until about early September to early December. (The bald eagle remains in New Jersey an “endangered” breeder – that is, in immediate jeopardy as a breeder – and “threatened” in general – that is, in danger of becoming “endangered” if conditions deteriorate.)

An adult bald eagle landing on the Upper Millstone River nest.

GARDEN WRITING: A great pleasure of mine is to be back at the Princeton Adult School this semester, again teaching non-fiction writing. In the past, I have taught the essay and the vignette. This semester, the course is called “Garden Writing,” but is really about gardens, the outdoors, or nature. Because of its title, the course has drawn a class of passionate gardeners. This passion inspires wonderful stories. Just this week, I have read papers about dandelions, beginning spring plantings indoors, tomatoes and their guests of the hornworm and Braconid wasp. The dozen or so in this class make it a joy to teach.

THINGS THAT DO NOT BELONG: Just because something is outdoorsy does not mean it belongs everywhere in the outdoors world. On the Millstone River on the boundary of East Windsor, Mercer County, and Cranbury, Middlesex County, I noticed ornamental daffodils growing in the river floodplain. I suspect these were purposely planted or they grew from waste soil. They looked pretty along the river, but they are a non-natives that do not belong there.

These daffodils look pretty blooming along the Millstone River on the boundary of Cranbury, Middlesex County, and East Windsor, Mercer County. But they are ornamentals that do not belong in the wild.

SKY PHOTOS: This week’s sky photos are from Monroe, Cranbury and Plainsboro, all in Middlesex County.

Sky above farmland in Monroe, Middlesex County.

Sky above farmland in Cranbury, Middlesex County.

Above my backyard in Monroe, Middlesex County.

Above farmland on the Cranbury-Plainsboro boundary, Middlesex County.

SUNRISE AND SUNSET: For the week of Sunday, April 15, to Saturday, April 21, the sun will rise about 6:20 to 6:10 a.m. and set about 7:35 to 7:45 p.m.

A Piedmont boulder field on the Princeton Ridge in Princeton, Mercer County. Notice the lichen growing on the rocks. Lichen is a sign of fresh air.

MOON: The next full moon is April 29, the Sprouting Grass Full Moon.

ATLANTIC OCEAN TEMPERATURE: The Atlantic Ocean temperature off New Jersey was about 46 to 52 degrees.

WEATHER: The National Weather Service office serving the Jersey Midlands is at https://www.weather.gov/phi/.

UPCOMING:

April 21, Saturday, 11 a.m. to 2 p.m., Burlington County, Southampton: The Pinelands Preservation Alliance’s 13th Annual Native Plant Sale, Alliance headquarters, 17 Pemberton Road (Route 616). More information is available from the alliance, telephone 609-859-8860 or website http://www.pinelandsalliance.org.

April 28, Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Middlesex County, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Ag Field Day, Cook Campus, Route 1 and Ryders Lane. More information is available at website http://agfieldday.rutgers.edu.

April 28 and 29, Saturday and Sunday, Hunterdon County, Lambertville: Shad Fest event of environmentalism, entertainment, food, crafts. More information is available at http://www.shadfest.com.

Daffodils in bloom in Cranbury, Middlesex County.

Joe Sapia, 61, is a lifelong resident of Monroe — in South Middlesex County, where his maternal family settled more than 100 years ago. He is a Pine Barrens naturalist and an organic gardener of vegetables and fruit, along with zinnias and roses. He loves the Delaware River north of Trenton and Piedmont, too.

He draws inspiration on the Pine Barrens around Helmetta from his mother, Sophie Onda Sapia, who lived her whole life in these Pines, and his Polish-immigrant grandmother, Annie Poznanski Onda.

He gardens the same backyard plot as did his Grandma Annie and Italian-American father, Joe Sr. Both are inspirations for his food gardening. Ma inspires his rose gardening.

Joe is a semi-retired print journalist of almost 40 years. His work also is at @JosephSapia on Twitter.com, along with The Jersey Midlands page on Facebook.com on the Jersey Midlands page.

Copyright 2018 by Joseph Sapia

Article and photos by Joe Mish

A red eyed vireo briefly descends from the treetops to provide a fleeting glimpse of one of the most common, yet rarely seen birds, east of the Mississippi.

March is the last piece of evidence needed to prove winter has gone by. No matter the weather March brings, her legacy of cold and snow, as the step child of winter, is invalidated by “the first day of spring” conspicuously stamped twenty-one days into the month on just about every calendar printed.

Further visual proof needed to allay the fear that winter is here to stay, are the strands of migratory birds that precede peak migration in the next couple of months. Perfectly positioned between two rivers that lead to the sea and link to the main Atlantic flyway, Branchburg comes alive with colorful winged migrants. Some birds are just passing through while others stay to establish breeding territories.

You don’t really need to be a graduate ornithologist with the ability to differentiate a magnolia warbler from a black throated warbler to enjoy all the feathered gems that pass our way in spring.

During a recent snowfall the view of several brilliant red, resident cardinals, dodging among the tight branches of a nearby holly tree resplendent in dark green leaves and an overabundance of red berries was a sight to behold. The gently falling snow turned the scene into a living Christmas card.

Bird seed scattered on the ground immediately near the back glass sliding door was being appreciated by a flock of brave juncos. The scene was calm and predictable with an occasional song sparrow darting across the stage. Suddenly, standing on the ground next to the glass was what appeared to be a Parula warbler. I ran for the camera to no avail as the little bird disappeared quicker than a shooting star. It didn’t seem plausible that a warbler would be in this area so early but there it was. Looking through the, ‘guide to field identification, Birds of North America’, I reviewed the dazzling array of warblers each differentiated by plumage unique to adult and juvenile, male and female with a cautionary note on hybrid warblers and seasonal plumage. I guess it was a male Parula warbler.

The conflict of identification versus the excitement at seeing a strange colorful bird lingered for a moment until I realized it was the sight of the bird that provided the magic.

Knowledge of the scientific classification was irrelevant to the enjoyment of simply noticing something that appeared to be different and gave pause to a moment of thoughtfulness or beauty.

As an example, you might gaze upon a stunning portrait of another person or a dreamy sunset and immediately be drawn in even though you have no idea of the person’s name or the location of the sunset.

Beauty is its own reward and needs no further qualification.

Birds are creatures which reflect the colors that dripped from God’s palette of infinite hues used to paint the portrait of life. One could argue ‘colors’ have wings to spread nature’s beauty far and wide and taken together they are called, ‘birds’.

Soon the area will be crowded with migrating birds, the most colorful of which are the warblers. A walk along the river flyways while scanning the treetops will reveal small flocks of birds that look like no other you have ever seen. The bright plumed breeding males will be the first to arrive as they travel in the safety of numbers. It is hard to imagine that these diminutive delicate appearing birds migrate yearly to Central America, Mexico and the West Indies from New Jersey and points north. After arriving in breeding areas, the males separate to set up mating territories defended by trilling songs sung loud and often.

The colorful and numerous male warblers representing several species are spectacular to observe in their diversity of color swatches, masks, vests, necklaces and caps. Each color pattern represents a different species despite similar size and intermingling of flocks.

Even the most ‘nature oblivious’ and ‘nature neutral’ observers may have their heads compulsively turned by the accidental appearance of a flash of tropical color among the local treetops.

Perhaps a seed of curiosity may be sown, nurtured and cultivated from a brief encounter with a spring warbler. That dangling thread of gangly curiosity left by a Magnolia warbler or Yellowthroat can easily draw the observer into the world of nature to wander and wonder at the infinite complexities that bind all living things. To believe beauty is only skin deep and fleeting is to ignore the power, depth and satisfaction the beauty of nature has to offer. Asking nothing in return, not even requiring that you can differentiate a Rufous sided towhee from a Cape May warbler, beauty exists only to be appreciated.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Eager and hungry fox pups survived the mercurial spring floods to feed voraciously on mom in the bright sunlight of a late April morning.

April is the quintessential month of spring, the first month to start with a vowel after a bleak winter of hard consonant constructed months. The name April is probably derived from the Latin infinitive, aperere, ‘to open’, but that consideration is at the risk of offending the claims of the goddess of love, Aphrodite, and Apollo the son of Zeus, their namesake month.

I see April as a grand series of ever changing dance steps performed in tune to the great celestial choreography of the planets and stars. One planetary misstep and the world comes crashing down. It is, however, a play without flaw that brings the predictability of the seasons and the impish April to improvise her set of daily surprises that precede the full bloom of May.

April is a charming minx with dancing green eyes whose mercurial ways give false hope to early gardeners as she whirls in the white robes of a sudden snow squall. Days of bright sunshine are mixed with bone chilling moist air, frosts and gentle rain or hailstorms of biblical proportion. These are the veils April sheds as she improvises dance steps to tease and mislead, all the while faithfully delivering the solemn promise of May.

Edwin Way Teale, a noted author and naturalist claims that, “spring approaches from the south at fifteen miles a day”. If you were to drive from New Jersey to Maine in mid April, you could actually see spring approach.

Travelling north, you go back in time to see spring begin.

As you drive through New Jersey, forsythia planted along road medians would be in full yellow bloom as tree buds give birth to pale green leaves.

The crowns of naturalized red maple dominated hardwoods would have shed their maroon veil to now wear a haze of light green unfurling leaves that will continue to darken as they mature

Oak dominated hillsides and lowlands scattered with black gum, hard maple, beech, ash and sycamore appear as colorful as autumn with interlacing crowns covered in non reflective red, yellow, pink and salmon hued emerging leaves.

The color and blooms slowly fade as you travel north. The further you travel in one day, the more the landscape appears as if drawn on individual sheets of paper flicked by hand to appear as if moving. The individual frames of the ‘movie’ become alive and reveal the living, leading edge of the manifestations of spring.

The return journey south allows you to enjoy the second coming of spring and the insight that comes with a second chance.

Along the South Branch, a Great Horned Owl has been nurturing a clutch of eggs that will produce at least one full sized, flightless owlet to stand constantly alert for parental food deliveries in mid April.

During two trips down the South Branch in February and March, a female red fox ran along the river bank to expose herself as if to draw me away from her riverside den. She would run along the bare vertical bank then walk out onto a gravel bar, sit down and watch me approach. When I got too close she would run off and wait further downstream. At one point she ran across a sand bar that was flanked by a pair of mallards standing on the bare ground and a great blue heron posed in foot deep water. All three birds stood perfectly still as the fox ran between them. Neither the ducks nor the heron made any move to escape as if they knew the fox was not a threat that day.

I can only hope the fox waited until April to have her pups in light of the flood that came in late March. Perhaps April will reveal a gentle rain that favors the survival of not only the fox pups, but the bank swallows, flycatchers, muskrat and turkeys that might have dens or nests close to the riverbank and flood plain.

It is amazing how migration, breeding, births and nurturing coincide with seasonal events as if truly participating in a dance whose every step is critical to survival.

We have evolved physiologically to fit into a small, ‘temporary’ niche circling in an eddy on the river of change. If the changes take place faster than we can evolve, we go away.

Despite the vagaries of April’s whim, she shows the world an emergence of life that has learned her fickle ways and dances in step to lovingly embrace such a wild partner.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.