Article by Joseph Mish, photos by Joseph Mish and Brian Zarate

A moment in the sun. The elusive and rare bog turtle, aka Muhlenberg turtle, is captured in this image by Brian Zarate.

The smallest and rarest turtle in NJ has emerged from the obscurity of its muddy bog to celebrity status as the bog turtle was recently named New Jersey’s state reptile.

The bog turtle was first scientifically cataloged by botanist Gotthilf Muhlenberg at the approach of the 19th century. In honor of the discoverer, this diminutive reptile was named Clemmys muhlenbergii. It was commonly known as the Muhlenberg turtle until the vagaries of taxonomic nuance christened it the bog turtle, one hundred and fifty-six years later.

The bog turtle averages a bit less than four inches in length. To visualize its size, write its scientific name on a piece of paper and that length will approximate the size of the turtle.

The blaze orange patch on the side of its head provides unmistakable and instant identification. The orange color glows like a brilliant gem. Stare at it for a moment and the turtle magically materializes from its muddy background.

The overall appearance of the turtle is a grayish black, though on closer inspection there are varying degrees of dull orange skin and freckles especially at the base of the front legs, neck and face. The carapace or ‘top shell’ is covered by ridged scutes or horny segments, comparable to fingernails. Faint amber markings may sometimes be seen on the shell, their appearance dependent on age or accumulated mud.

The small size, secretive habits and specialized habitat requirements restrict the presence of this turtle to very defined regions of the state.

As its name suggest, these turtles prefer open boggy areas fed by clear springs or streams. Skunk cabbage and jewelweed, aka, ‘touch me not’, are easily identifiable plants commonly found in bog turtle habitat. Pasture lands are desirable locations as plants and grasses are kept in check by grazing cows to maintain optimum preferred habitat. Deep mud, constantly infused with spring water, provides ideal hiding places and protection from freezing during winter hibernation.

Tree stumps protruding from the bog and raised islands are preferred locations to lay eggs. Females seek these drier places within the bog to lay eggs as opposed to other turtle species which travel quite far from home.

To illustrate the secret life of the bog turtle, a friend who was a conservation officer, stopped to investigate a car parked alongside a road in north Jersey. He came upon two researchers following signals from a bog turtle equipped with a transmitter as part of a study project. Nothing could be seen to indicate a turtle was present. The signal, however, indicated its precise location and after digging deeply into the mud, there was the turtle alive and well!

Bog turtles are considered to one of the rarest turtle species in the United States.

The bog turtle had been declared ‘endangered’ by the state in 1974 and ‘threatened’ by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1997. Population estimates are speculative, as some articles cite the total population in the eastern US as 2,500 to 10,000 and ‘fewer than 2,000’ turtles in NJ. The Bog Turtle Project states 168 colonies have been identified. Equal distribution of 2,000 turtles over 168 locations cannot be assumed and further emphasizes the rarity of this precious gem.

Among the locations identified, there are a select few, which have a large enough gene pool to ensure a viable population into the future. While turtles found in isolated micro habitats are vulnerable to insufficient genetic variation.

In both situations the loss of contiguous habitat is a deadly threat, as a segmented environment limits migration and thus genetic variation as well as exposing animals to predators, mowers and vehicles.

Loss of habitat is a major threat to bog turtles as well as many other species.

Invasive plants, like the familiar purple loosetrife and phragmites, dominate areas to destroy plant diversity and alter soil porosity which in turn eliminates the cascade of insect and invertebrate life upon which the bog turtle feeds.

purple loosestrife invasive plant chokes out native grasses reduces invertebrate diversity

More turtles may yet be found by wild chance, though by no means can their presence be considered widespread as is the case with more common species like painted and snapping turtles.

Suffice to say the description of ‘rare’ is understated when used to describe the bog turtle.

The designation of ‘state reptile’ is not an endearing term to the general population. I like to think of the bog turtle, as one in a series, of New Jersey’s unheralded natural treasures.

Read about the NJ Bog Turtle project at

https://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/bogturt.htm

More references for bog turtle information.

https://www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/ensp/pdf/end-thrtened/bogtrtl.pdf

http://www.conservewildlifenj.org/species/fieldguide/view/Glyptemys%20muhlenbergii/

Should you find a bog turtle, report it and keep the location secret, as this turtle is high on the list of the illegal wildlife trade.

Report any discovery to the state at: https://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/ensp/rprtform.htm

Whenever I see a turtle, I always wonder how old it might be and compare it to events in my life. Most age ranges provided for wild creatures are speculative and based on captive animals or hard data collected from tagged wild animals. A bog turtle tagged in 1974 and estimated to be about 30 plus years at the time was again found in 2017, which places its estimated age at around 65 – 70 years old! That age range allows young and old to ponder what was going on in their life at any point in that turtle’s parallel life.

Thirty something years ago when that turtle burrowed deep into the mud to hibernate, my daughter was born in Muhlenberg hospital. A local hospital named after the son of the discoverer of the bog turtle, aka Muhlenberg turtle. The legislation to proclaim the bog turtle the official state reptile was co-sponsored by Kip Bateman of Branchburg. It would be a further coincidence to find and report the discovery of a bog turtle community within Branchburg!

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

My South Branch office is made of kevlar and weighs 52#, well lit with natural light and leaves no trace. A perfect vehicle for discovering New Jersey’s natural treasure hidden in plain view.

Every once in a while, it is useful to check your back trail to validate your current course. For the last few years I have been attending the Rutgers sponsored, ‘Annual Sustainable Raritan River Conference’ and was introduced to the people and effort dedicated to improve the water and land that make up the Raritan River basin.

It was strange at first to hear someone else talk about my river. There was a moment of concern, a tinge of jealousy, that my ownership of the river was being usurped by strangers, some not even native to New Jersey. I soon realized I was among kindred spirits. It was like meeting long lost relatives….. whose company you sincerely enjoyed. Each member contributed a critical piece of the puzzle, whether a citizen, volunteer or a degreed scientist, each perspective complimented the other, and occasionally there was the discovery of a piece no one knew was missing. The symposium took the threads of individual effort and wove them into a whole cloth.

I was pleasantly surprised, the focus of the conference dovetailed perfectly into my goals and objectives. It also prompted me to revisit what I hope to accomplish with my images and words, given the current status of New Jersey’s relationship with its natural treasures.

Today New Jersey enjoys a natural inheritance that is the sum of the legacy left by generations of agrarian, industrial and residential development. Sacrificed in the name of progress, our natural and wild treasures are reputed to have been diminished to a vanishing point in the wake of the great human juggernaut. However, despite New Jersey’s recurring reputation as the most densely populated state in the union, wildlife is found to proliferate along its river corridors, highways, woods and fields. Much of this wildlife existed before the establishment of farms, whose disappearance falsely signals the surrender to unabated construction and development. The farms and cows are actually late-arriving interlopers, highly visible and used as a convenient but inaccurate measure of our intrinsic wild and natural resources. It is the presence or absence of cows that form the basis for politically subjective land use decisions.

Even the most ardent nature-oriented residents are often oblivious to the richness and distribution of this state’s natural treasures. Regional areas, reputed as nature destinations, add to obscure our natural treasures as their existence implies an absence of nature except where designated. Combine this with the perspective of the nature-neutral and nature-oblivious residents and it is understandable how the nature sterilized image of New Jersey arises from within and grows with distance to earn a national and global reputation as “the ghost of nature past”.

Against this background my photographic intentions range from historic documentation of ephemeral wild moments to portraiture revealing the energy and dignity of the creatures that covertly exist among us. What the camera misses the words capture, what the camera sees the words enhance.

The articles are a blend of literary flourish embedded with scientific information as much for entertainment as to arouse curiosity. I wish to create a gravitational pull of curiosity that draws the reader to seek deeper knowledge. Hopefully some youngster will be intrigued enough to pursue more detailed information and perhaps launch a career in science.

One reason New Jersey’s natural treasures remain hidden in plain view is because of prejudice and limited expectation. The best way to remedy this, is to change the lens through which our natural world is viewed. I do this by presenting stories and information from unique perspectives, along with images of wildlife most have never seen and many more don’t believe exist so close to home.

When I consider my place in the effort to restore the rivers, I see me operating on the interface between art and science. I walk that line to help transition attitudes and open eyes to a new reality fostered by creativity and imagination.

Rutgers fish camera at Island Weir Dam on the Raritan River is now online.

http://raritanfishcam.weebly.com

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Another magic moment revealed itself in a face to face encounter with a deer fawn enjoying the cool water of the South Branch. The pattern and contrast of spots on the fawn is reminiscent of the firefly spectacle and becomes a walking billboard for the upcoming bioluminescence night show.

While September marks the celestial end of summer, it does little to extinguish the glow of lingering warm weather memories that ebb and flow well into the cold months. The longest lasting memories often have a magical quality about them. Sometimes the spell only lasts until the event can be explained and sometimes the magic can’t hold a candle to its reality.

This year mid to late June showcased a bumper crop of fireflies or lightning bugs as they are often referred. Who hasn’t seen a lightning bug flitting around their yard? Big deal! Well it is a big deal if you see the intense display of luminescence played out in a grassy pasture surrounded by tall trees on a moonless night.

Beginning just before dark, with a growing intensity, the concentrated fireflies put on a dynamic light show guaranteed to hold your attention until the curtain begins to fall at around 11 pm. Strangely enough the moving flashes of bright yellow light contrast against the black darkness to steal away any perception of depth or relative position. Stare long enough and you might lose your balance. The scale, intensity and contrast of this visual phenomenon does much to anesthetize any thoughts of logic and scientific understanding from creeping in to spoil the moment. The experience is heightened by our primal esteem of fire and light to reflect upon our souls as we surrender to the magical display of luminescence.

Fireflies are the stuff of childhood memories. Many a captive luminary flashed a desperate signal through the clear glass of a Skippy peanut butter jar. Our fascination soon ended with puberty to become an unremarkable footnote in our adult lives.

Read on and you might want to salute every time you see a lightning bug.

Fireflies belong to the family Lampyridae, so even without knowing Latin, the assignment makes sense. It was about 1948 that the luminescence was isolated but unusable until years later when sufficient quantities of the material could be produced. The firefly’s light is created by using a combination of luciferin, an enzyme named luciferase and ATP. Lucifer in Latin can be translated as ‘light giver’. Lucid is a word that means clear and derives from the Latin word for ‘light’. To the uninitiated luciferin sounds like something the devil had a hand in. Amazingly when compared to a misnamed “light bulb” almost all of the lightning bug’s light energy goes to creating light while the “light bulb” is said to produce 10% light and 90% heat.

Typically poisonous plants and animals are brightly colored to warn away potential predators. So it is with lightning bugs that they contain a substance similar to digitalis. Veterinary journals report many exotic lizards kept as pets die each year when owners try to vary the pet’s diet by feeding them lightning bugs

Worldwide there are many species of fireflies. Our local bugs display the luminescence as adults and as larvae. In fact the larvae are predatory and eat earthworms by injecting a mix of enzymes and probably anesthetic into the worm and then sucking out the blended juices. Often referred to as glow worms, firefly larvae will intensify their light when stressed not unlike you turning red in anger or embarrassment.

Female fireflies climb onto tall grasses or shrubs as they cannot fly. All the flashers cavorting in the night sky are the males. When a female finds a flash pattern she likes she signals to the male in similar fashion to ‘come on down’.

Recently with the advent of genomic research and the clinical application of gene therapy, bioluminescence has been recruited to make stunning inroads into medical research. Attaching a bioluminescent gene to a cancer cell allows researchers to follow the progression of cancer cells from the moment they are injected into animal models. Up until now, researchers would have to wait months after inoculating animals with cancer cells to see the manifestation of clinical or laboratory effects. The incubation period for tumor production was a blind spot that has now been revealed with the help of the common firefly. Immediately the distribution of cancer cells can be followed as it spreads through the body and does battle with our rather effective immune system. Immediately the effectiveness of cancer therapies can be tracked and adjusted or changed.

These light producing cells can be attached to bacteria as well in the study of anti-infective drugs. Imagine a visual image of bacteria spreading throughout an animal’s body, injecting medication and seeing immediately the effectiveness of the trial drug and dosage.

Last of all consider the myth surrounding the old favorite Beatles tune, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”. Most Beatle’s fans agree the title of the song came from the Fab Four’s immersion in the psychedelic drug culture. I, however, contend the song was named after watching a mid summer’s spectacle of lightning bugs flashing in the sky like diamonds courtesy of Luci- ferin and Luci-ferase.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Rose gets a green aluminum band affixed to her left leg and a silver band to her right leg. Green is the band color used by NJ and silver is a federal band. Each state uses a specific color to quickly identify a banded eagle’s origin.

Over last century as the northeast bald eagle population dwindled, their image flourished as a marketing tool to brand high end merchandise. Gilded eagles sat upon flag poles in parades and auditoriums. Dollar bills and quarters bore engraved, lone eagles, wings spread and talons flared, about to attack at the least provocation.

Never did any image show more than one eagle, even though they mate for life and are dedicated parents. As a generation, we came to know eagles as powerful solitary creatures frozen in iconic poses. There was nothing to challenge that image, the skies were empty and no shadows could be seen speeding across the land. Least of all in central NJ, a land reputed to be sanitized of nature.

Awareness of man’s place in the natural world and his impact on the environment began to be studied in universities like Rutgers College of Agriculture and Environmental Science in the late 1960s, which opened the door to a new era of enlightenment and activism. Books like Silent Spring and Sand County Almanac were the seeds sown to nourish the idea humans were not apart from the cascade of life that flowed, uninterrupted, from the soil and water to apex predators, like the eagle and peregrine falcon.

Eagle restoration in NJ began in earnest in the 1980s accompanied by an ever-growing accumulation of study data gleaned by observation and scientific research. Still the view of intimate eagle relationships and social interaction remained at a sky-high level and not well published for public consumption.

Eagles kept their privacy and legacy reputation as solitary creatures intact until the advent of live cameras, genetic mapping, banding and miniature transmitters.

As far as the public is concerned, it is the live cams, set above some nests and broadcast on the internet, that provide non-stop coverage of eagle antics in the aerie to feed an insatiable voyeuristic human appetite.

The forums that accompany these spy cams generate lively conversation and together, have created a whole new audience beyond those immersed in all things nature. People who can’t tell a snow goose from a snow bunting, are now addicted a wildlife reality show.

And addictive it is, as viewers and scientists both learn what goes on behind nest walls. As voyeurs watch, they see behaviors that mimic human responses. The eagle screaming at its partner could very well be a replay of last night’s argument with their spouse, “who never listens to a word I say”.

Cumulatively, what we see are personality differences among pairs of eagles, where before we had only anecdotal observations and generalized conclusions. We knew the eagle as a solitary warrior and now we see a great raptor dedicated to its mate and offspring. When we look closely into the world of an eagle we see a glimpse of ourselves.

Locally the intrigue has been riveting, with a ringside seat to a female ingénue coming between a mated pair, a harassing hawk obliterated by an annoyed eagle and tender moments of dedicated parents doting on their precious offspring.

We watch as courting behavior evolves into mating, egg laying and alternate job sharing, as pairs relieve each other from brooding duty. We see and hear the wailing of one parent when their mate fails to return, either through injury or death. You cannot be unaffected by that sight and sound as what you experience is automatically translated into human terms.

A live cam from another state showed a female eagle covering her three, day old chicks, as a late spring snowstorm raged. That moment was tender enough but then the male positioned himself alongside the female, resting his head on her shoulder and spread his wings to shield his mate and their chicks from the heavy snowfall; our collective tears flowed.

Recently an eagle that prematurely fell from a local nest was rescued, examined and found to be in good health. Given that one parent went missing in the weeks prior to the fall and it was impossible to return the bird to the nest, a decision was made to place that eagle in another nearby nest.

Armed with the knowledge of intimate eagle behavior and demonstrated dedication to their young, fostering that young eagle was done with full confidence it would be accepted and thrive.

Only time will tell but so far, so good. Years hence, if you see a bald eagle bearing a green leg band, engraved with E68, you now know the rest of the story. Consider an eagle that was killed, June 2015, in upstate NY by a car, was banded 38 years prior! So, eagle E68, affectionately named, Rose, and her foster siblings, E66 and E67 have a good chance to be seen by your grandchildren!

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

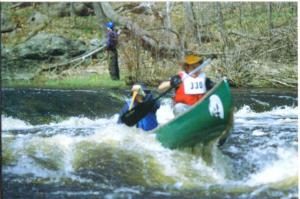

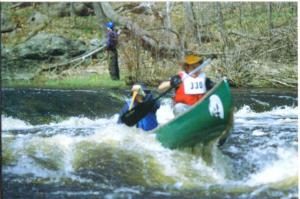

The powerful watery hand of the river reaches up in a wild mood to toss its dance partner skyward.

A canoeist might think of the river as a dance partner whose energy flow and mood sets the tone for the style of dance to be performed. A waltz, a tango or lambada are all on the river’s dance card to be enjoyed or sat out. Any paddler who wishes to partner with the river and enjoy the wide variety of watery tunes must have practiced moves, familiarity with boat and paddle and an ability to read the subtle nuance of wave patterns reflecting the structure of the hidden riverbed.

While high water and low water dances may be thoroughly enjoyed, I originally coined the term ‘river dance’ to describe the convoluted navigation required to follow the low water flow typically occurring on the South Branch during the summer.

Each year, winter ice and downed trees reshape the river bed to form new shoals, islands and channels which leave the scars and wrinkles that figure so prominently when water levels drop in the summer.

Low water and limited paddler skill do not preclude a float trip down the river as a grounded boat may be dragged across exposed shoals and shallows to deeper water.

Plodding along does not equate to river dancing but it gets the job done.

The joy of river dancing comes into play when the paddler, perhaps in a solo canoe, seeks out cuts and channels that hold just enough water to support the boat. Following the deepest water when the riverbed becomes a player in the band may mean tracing a convoluted course from one side of the river to the other. This shallow water navigation strategy is directly applicable to high, fast water flowing through boulder strewn stretches of river. Both situations require reading the wave patterns to determine the best path beyond the next immediate move.

One fast water section where I launch always has sufficient water from bank to bank for about a hundred yards. During lower water levels the left side and most of the middle of the riverbed is almost exposed and not navigable except for a narrow cut quite close to river right. As is often the case, a direct downstream approach to the deep water cut is not possible because the water directly above the cut is too shallow or has a downed tree blocking that approach. As the situation and solution is obvious from a long distance upstream there is time to gradually approach the passage at a forty-five degree angle and then straighten the boat with a quick draw to follow perfectly in the strong deep current.

Further downstream near a bend in the river, a long treeless island appears, the right side of which is navigable in a channel that runs along the opposite bank. As the channel nears the end of the island, it flattens out and disappears. The water then seeks to run at an angle across the raised center section of the riverbed. The riverbed here appears to have a profile of a typical crowned roadway and the main channel reappears to run just along the tip of the island. Crossing the riverbed from one channel to the other requires a good look at the wave patterns. If you know nothing, then just observe the differences in the wave patterns. In very shallow water they are almost indistinguishable but with practice differences will become apparent. Generally, flatter waves reflect deeper water. Or simply put, the less busy the surface of the water appears, the further above the riverbed it is. Don’t be surprised sometimes to find the water too shallow despite choosing the most favorable pathway. Crossing an ultra shallow channel as described, may require the paddler to shift their weight forward to create an absolute neutral balance in the boat to avoid a fore or aft drag. Shifting paddler weight to one side in a typical shallow V-shaped hull will often decrease the depth the hull protrudes into the water and might make the difference between stepping out and dragging the boat or barely floating by with some slight scraping.

One of the most useful skills a paddler can acquire is the ability to ferry. A ferry is a method which allows cross stream travel in swift water with minimal paddler effort.

I usually stop to do a ferry whenever fast water presents itself just because it is so much fun and feels like magic. A ferry is based on the premise that a canoe becomes invisible to the current when perfectly aligned with the water flow. A canoe can be paddled upstream and held in position without any downstream travel when the hull is parallel to the water flow. Eventually when the hull begins to angle across the current the boat will be washed downstream. The speed with which the boat is carried downstream depends on the angle of the boat to the water flow. The greater the hull angle, the greater the surface area the current has to push against. A ferry is possible when the boat is angled into the current and that angle held steady by the paddler. Very fast water requires a shallow angle to be held, the slower the water speed the greater the angle needed to perform a ferry.

Often the current speed changes as you cross the river and the boat’s position must be adjusted appropriately. The magic occurs when you realize the boat, held at the proper angle, begins to cross the current from one side to the other without any downstream travel!

A ferry can be accomplished with the bow upstream or downstream. Simply angle the upstream end of the boat in the direction of the shore you wish to reach. In very fast water you might suddenly find yourself at the precipice of a ledge with no chance of safe passage. Not to worry. Straighten the hull with any and all paddle strokes that might be applicable, hold the boat steady. Choose your angle and be amazed as your boat becomes a magic carpet to drift you above the ledge, perpendicular to the current, and on to a safe passage or convenient eddy.

Do not despair when summer water levels fall and most folks abandon the thought of paddling the local rivers. Armed with patience and agility you might try to dance with the river on her terms.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Looking up into the columbine flower’s mouth, I see a dove with wings spread or an angel. This diminutive wild flower is found in isolated patches among the red shale cliffs that line the South Branch. Who knew, other than hummingbirds, that such a treasured crown jewel was hidden along our river.

The red shale cliffs interrupt pasture and field along the South Branch to stand as an unchanging reference point, immune to progress and raging spring floods that swirl around them.

The exposed cliff face is characterized by a jagged appearance, with sections of smooth rock face the exception. Ancient floods have scoured rounded contours into the soft shale, to form shallow caves, nooks, crannies and alcoves. Like a human face with striking character, the cliffs beg more than a casual glance.

I cannot paddle by without desperately searching the high cliff face for ancient etchings or a petroglyph. Travelers from earliest times could not have passed up an opportunity to scribe their name or draw their hunting or fishing trophies into the smoother areas of these red shale sketchpads. It would be against human nature to leave no sign.

Unexpectedly, what I have found among the craggy shale cliffs is a species of native wildflower that begins to bloom in late April through May. Wild columbine is not found anywhere else, except in the crevices of the prominent shale outcroppings along the river.

Columbine is a finely structured red and yellow flower, in the shape of a crown with five distinct tubular projections. The openings of the five separate passages are shrouded in a common vestibule. Several stalks arise from one clump, one flower to a stem, opening faces downward. The plant is not found in profusion, just in scattered, isolated patches.

There are many commercial cultivars and species of columbine, so to be clear, the wild native columbine is Aquilegia columbine. The derivative of the name is interesting as, ‘Aquila’, is Latin for eagle, and columbine references the family designation of doves. Early taxonomists saw characteristics of both in the flower. It is said the ‘spurs’ resemble the open talons of a raptor and the face of the flower, a nest of doves. To me the spurs that project to form the crown remind me of the reversed leg joint of a grasshopper when viewed from a certain angle and looking up into the mouth of the flower, I see the form of a single dove with wings spread.

The columbine flower produces tiny round black seeds in late May that are indistinguishable from poppy seeds. Though the columbine blooms about the time the first migrating hummingbirds show up, I have yet to catch a hummer dining on the flowers but surely some returning hummers have the plants marked on their GPS.

How and when columbine first found anchorage in these cliffs is a mystery. In the absence of its known origins, I prefer to think of these flowers as inheritance from an ancient legacy of primitive plants. The first of which relied on wind for propagation and then, as if by the hand of an engineer, designed shape, color and form to take advantage of insect pollinators and local soil conditions. Could it be that flowers intelligently made use of the cliffs to mark their presence through the centuries where humans left no trace?

Wild columbine are the crown jewels hidden among the cliffs, that appear in the spring for a brief moment to enrich both pollinators and humans who stumble upon them.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

A hummingbird and orange trumpet flower engage in an evolutionary dance of equal partnership that has lasted for eons. The flower not only took advantage of an array of pollinators but also stole the heart of man who would seek to propagate flowers far beyond their natural range and ability to survive.

A name logically follows the existence of an idea, a person, place or a thing and forever provides an instant reference, complete with assigned identifiable characteristics. So before there was a month named May, a segment of time existed in nature where birth and bloom dominated the season.

The mythology from which the name of May arose was based on the same natural observations seen today. Stories of the stars and the gods became the reference points displayed on the night sky overhead projector to help explain observed phenomenon. The poetic phrase, “April showers bring May flowers” provides information sufficient enough for most people to understand the season. Instead of placing flowers at the altar of the goddess Maia we now send flowers to our mothers on a day designated to show her our appreciation, same story, different day.

Going back to the time before May, can you imagine discovering the first flower ever to bloom? In retrospect it would have meant that some plant had evolved to take advantage of a new method of pollination that relied on insects rather than wind. At the time of discovery, however, the moment had to be absolutely magical. Here was something so different in structure, color, scent and profusion that it instantly intensified a fledgling human emotion that speaks to the appreciation of beauty. The flower not only took advantage of insect pollinators but at that moment stole the heart of man who would later seek to propagate flowers far beyond their natural range and ability to survive.

Watching a rambunctious fox pup at a distance, I saw what appeared to be orange pollen on its solid black nose. As the pup was playing around the daylilies I imagined he stuck his nose inside a funnel shaped orange flower, designed for bees and hummingbirds, to come away with the telltale signs of brightly colored pollen grains. If he sniffed a few more flowers he actually became the “bee” and a willing, if not random, participant in asexual reproduction. The part that serendipity plays in nature and science can never be underestimated and its potential never unappreciated when unprecedented success results.

Fox pups are not the only pollinators unknowingly pressed into service by the ingenious evolutionary design of flowers. It is a laugh riot, for some reason, to see a dusting of yellow or orange pollen on the nose of a child or adult who sniffs a flower in pursuit of its scent. Eyes closed, as if about to plant a kiss, the human pollinator presses forward until nose touches stamen.

The entire event, so instinctive and innocently conducted, that the “bee” comes away unaware of its role in the evolutionary drama of species reproduction and survival. A kind friend will of course bring attention to the dusting of pollen left by such an intimate encounter and be trusted to address it discreetly.

Bees of all kind have ‘pollen baskets’ on their back legs which hold an accumulation of pollen grains that appear as large colorful round beads on opposite back legs. Watch one of those big furry yellow and black bees and you can easily see the lumps of colorful pollen that varies from flower to flower.

Paddling along the south branch, wild columbine can now be seen in select places on north and west facing red shale cliffs. These delicate plants grow from roots wedged between the layered red shale well above the surface of the water. The reddish pink tubular flowers with a common yellow center resemble a group of ice cream cones joined to form a common opening which leads to several individual tails. This structure encourages contact with the centrally located pollen that has to be brushed against in order to reach several sources of nectar located in each tail. This flower must have had a hummingbird sitting on the design team who decided not only the flowers structure but the time the flower was set to bloom. Hummers arriving in early spring from Mexico and Central America have a ready source of food to replenish the energy spent in their annual migration north.

Consider the greatest mayflower of all and the part it played in another notable migration. The “Mayflower”, was a ship that sailed to our shores bearing its human pollen to establish new life on the North American continent The ship, so named by unknown whimsy and intended as a supply barge, grew to evolve much as early flowers did into an effective delivery system directed by nothing more than chance. Like a flower it bloomed, spread its pollen and ‘died back’ soon after returning to England.

May apples, Virginia bluebells, trout lilies, trillium, jack-in-the pulpits and spring beauties are a small sample of local May flowers that represent the spectrum of a floral legacy whose genealogy traces back to the earliest flowers. Consider that flowers are living things that in some magical way recruited man to further their propagation in exchange for a glimpse of eternal beauty, dreams and imagination to expand the universe of human potential with unbounded creativity and expression.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

A red eyed vireo briefly descends from the treetops to provide a fleeting glimpse of one of the most common, yet rarely seen birds, east of the Mississippi.

March is the last piece of evidence needed to prove winter has gone by. No matter the weather March brings, her legacy of cold and snow, as the step child of winter, is invalidated by “the first day of spring” conspicuously stamped twenty-one days into the month on just about every calendar printed.

Further visual proof needed to allay the fear that winter is here to stay, are the strands of migratory birds that precede peak migration in the next couple of months. Perfectly positioned between two rivers that lead to the sea and link to the main Atlantic flyway, Branchburg comes alive with colorful winged migrants. Some birds are just passing through while others stay to establish breeding territories.

You don’t really need to be a graduate ornithologist with the ability to differentiate a magnolia warbler from a black throated warbler to enjoy all the feathered gems that pass our way in spring.

During a recent snowfall the view of several brilliant red, resident cardinals, dodging among the tight branches of a nearby holly tree resplendent in dark green leaves and an overabundance of red berries was a sight to behold. The gently falling snow turned the scene into a living Christmas card.

Bird seed scattered on the ground immediately near the back glass sliding door was being appreciated by a flock of brave juncos. The scene was calm and predictable with an occasional song sparrow darting across the stage. Suddenly, standing on the ground next to the glass was what appeared to be a Parula warbler. I ran for the camera to no avail as the little bird disappeared quicker than a shooting star. It didn’t seem plausible that a warbler would be in this area so early but there it was. Looking through the, ‘guide to field identification, Birds of North America’, I reviewed the dazzling array of warblers each differentiated by plumage unique to adult and juvenile, male and female with a cautionary note on hybrid warblers and seasonal plumage. I guess it was a male Parula warbler.

The conflict of identification versus the excitement at seeing a strange colorful bird lingered for a moment until I realized it was the sight of the bird that provided the magic.

Knowledge of the scientific classification was irrelevant to the enjoyment of simply noticing something that appeared to be different and gave pause to a moment of thoughtfulness or beauty.

As an example, you might gaze upon a stunning portrait of another person or a dreamy sunset and immediately be drawn in even though you have no idea of the person’s name or the location of the sunset.

Beauty is its own reward and needs no further qualification.

Birds are creatures which reflect the colors that dripped from God’s palette of infinite hues used to paint the portrait of life. One could argue ‘colors’ have wings to spread nature’s beauty far and wide and taken together they are called, ‘birds’.

Soon the area will be crowded with migrating birds, the most colorful of which are the warblers. A walk along the river flyways while scanning the treetops will reveal small flocks of birds that look like no other you have ever seen. The bright plumed breeding males will be the first to arrive as they travel in the safety of numbers. It is hard to imagine that these diminutive delicate appearing birds migrate yearly to Central America, Mexico and the West Indies from New Jersey and points north. After arriving in breeding areas, the males separate to set up mating territories defended by trilling songs sung loud and often.

The colorful and numerous male warblers representing several species are spectacular to observe in their diversity of color swatches, masks, vests, necklaces and caps. Each color pattern represents a different species despite similar size and intermingling of flocks.

Even the most ‘nature oblivious’ and ‘nature neutral’ observers may have their heads compulsively turned by the accidental appearance of a flash of tropical color among the local treetops.

Perhaps a seed of curiosity may be sown, nurtured and cultivated from a brief encounter with a spring warbler. That dangling thread of gangly curiosity left by a Magnolia warbler or Yellowthroat can easily draw the observer into the world of nature to wander and wonder at the infinite complexities that bind all living things. To believe beauty is only skin deep and fleeting is to ignore the power, depth and satisfaction the beauty of nature has to offer. Asking nothing in return, not even requiring that you can differentiate a Rufous sided towhee from a Cape May warbler, beauty exists only to be appreciated.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Eager and hungry fox pups survived the mercurial spring floods to feed voraciously on mom in the bright sunlight of a late April morning.

April is the quintessential month of spring, the first month to start with a vowel after a bleak winter of hard consonant constructed months. The name April is probably derived from the Latin infinitive, aperere, ‘to open’, but that consideration is at the risk of offending the claims of the goddess of love, Aphrodite, and Apollo the son of Zeus, their namesake month.

I see April as a grand series of ever changing dance steps performed in tune to the great celestial choreography of the planets and stars. One planetary misstep and the world comes crashing down. It is, however, a play without flaw that brings the predictability of the seasons and the impish April to improvise her set of daily surprises that precede the full bloom of May.

April is a charming minx with dancing green eyes whose mercurial ways give false hope to early gardeners as she whirls in the white robes of a sudden snow squall. Days of bright sunshine are mixed with bone chilling moist air, frosts and gentle rain or hailstorms of biblical proportion. These are the veils April sheds as she improvises dance steps to tease and mislead, all the while faithfully delivering the solemn promise of May.

Edwin Way Teale, a noted author and naturalist claims that, “spring approaches from the south at fifteen miles a day”. If you were to drive from New Jersey to Maine in mid April, you could actually see spring approach.

Travelling north, you go back in time to see spring begin.

As you drive through New Jersey, forsythia planted along road medians would be in full yellow bloom as tree buds give birth to pale green leaves.

The crowns of naturalized red maple dominated hardwoods would have shed their maroon veil to now wear a haze of light green unfurling leaves that will continue to darken as they mature

Oak dominated hillsides and lowlands scattered with black gum, hard maple, beech, ash and sycamore appear as colorful as autumn with interlacing crowns covered in non reflective red, yellow, pink and salmon hued emerging leaves.

The color and blooms slowly fade as you travel north. The further you travel in one day, the more the landscape appears as if drawn on individual sheets of paper flicked by hand to appear as if moving. The individual frames of the ‘movie’ become alive and reveal the living, leading edge of the manifestations of spring.

The return journey south allows you to enjoy the second coming of spring and the insight that comes with a second chance.

Along the South Branch, a Great Horned Owl has been nurturing a clutch of eggs that will produce at least one full sized, flightless owlet to stand constantly alert for parental food deliveries in mid April.

During two trips down the South Branch in February and March, a female red fox ran along the river bank to expose herself as if to draw me away from her riverside den. She would run along the bare vertical bank then walk out onto a gravel bar, sit down and watch me approach. When I got too close she would run off and wait further downstream. At one point she ran across a sand bar that was flanked by a pair of mallards standing on the bare ground and a great blue heron posed in foot deep water. All three birds stood perfectly still as the fox ran between them. Neither the ducks nor the heron made any move to escape as if they knew the fox was not a threat that day.

I can only hope the fox waited until April to have her pups in light of the flood that came in late March. Perhaps April will reveal a gentle rain that favors the survival of not only the fox pups, but the bank swallows, flycatchers, muskrat and turkeys that might have dens or nests close to the riverbank and flood plain.

It is amazing how migration, breeding, births and nurturing coincide with seasonal events as if truly participating in a dance whose every step is critical to survival.

We have evolved physiologically to fit into a small, ‘temporary’ niche circling in an eddy on the river of change. If the changes take place faster than we can evolve, we go away.

Despite the vagaries of April’s whim, she shows the world an emergence of life that has learned her fickle ways and dances in step to lovingly embrace such a wild partner.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and photos by Joe Mish

The sea run shad, striped bass and herring that gather at the mouth of the Raritan River attract animals high on the food chain such as this harbor seal. Whales and dolphin have also been sighted over the last few years not in small part from the contribution of the Raritan River and its sweet water branches.

The spring-fed north and south branches of the Raritan River join in a marriage of sweet water at their confluence, on an endless journey to the sea. Each hidden spring and brook along the way, contributes its own genetic identity, mixed in a final blend at the mouth of the Raritan River.

Where the fresh water meets the salty sea, the ebb and flow of tides stir the brine into fresh water to create a stable buffer zone of brackish water.

These back bays and estuaries formed at the mouths of rivers are a perfect place for young of the year striped bass to gain in size before going offshore to migrate. American, hickory, gizzard shad, river herring, such as blueback herring and alewives also gather here and search for ancient breeding grounds located far upriver.

In the time before dams, sea run fish migrated far upstream into the north and south branch. Fishing was a robust industry in early colonial times where the seasonal migration of herring and shad was a profitable business.

The construction of dams to power mills along the river put a halt to upstream commercial fishing. The mills and dams were not welcomed by colonists who made a living from the seasonal fisheries. One account tells of early settlers in the mid 1700s, unhappy with a mill dam just below Bound Brook, making nightly raids to dismantle the dam and allow shad to continue their upstream migration.

Fast forward to today, the river still flows to the sea and the shad and herring gather to swim upstream.

In 1985 pregnant shad from the Delaware River were transplanted to the South Branch as part of a program to restore a shad migration along with planned dam removals.

Dams that have blocked migrating fish have recently been removed. The Calco dam near the former Calco Chemical Company built around 1938, cleared the way for migrating fish to reach the confluence of the Millstone and Raritan where a flood control dam was built. Known as the Island Farm weir, completed in 1995, it includes a viewing window and fish ladder to allow the dam to be bypassed by fish travelling upstream.

As part of the shad restoration project, volunteers working with Rutgers scientists tag shad and herring in an ongoing effort to gauge the success of the fish ladder and restoration efforts. Preliminary findings can be accessed at, http://raritan.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NJDEP-2013-American-shad-restoration-in-the-raritan-river.pdf

A live underwater camera is placed at the dam each year after threat of ice has past. The camera is now operated by Rutgers University and may be seen online at http://raritanfishcam.weebly.com/fish-guide.html and at http://raritan.rutgers.edu/resources/fish-cam/

Aside from the Calco dam, three of five dams upstream of the Island Farm Weir, two dams on the Raritan, the Nevius street and Robert street dam and one on the Millstone have been removed. All in anticipation that the head dam at Dukes Island Park and the low dam at Rockafellows Mills on the South Branch will eventually be deconstructed.

See the above link for the video of the Nevius street dam removal. Go to MENU, open videos/multimedia to see Nevius street dam deconstructed.

See this link for a look at the Duke’s Island dam today; https://vimeo.com/259404286

The dream to restore our rivers and fisheries to their unmolested glory is well on the way to reality. Bald eagles now nest along the Raritan and its branches, soon to be joined by spawning shad and herring.

The vision of a pristine river valley, interrupted by 300 years of abuse and neglect is slowly emerging from the river mist as a magical apparition. The magic supplied by the hard work of Rutgers scientists and dedicated volunteers who echo the words of Rutgers president Thomas, who served in 1930, “Save the Raritan”.

As an aside to this article, I will share a sobering and emotional experience involving the Island Weir Dam that took place in 1995. The intent is to emphasize the importance of safety while paddling in general and especially when near dams or in cold water.

See page three of this link for a description of what happened that day: http://www.wrightwater.com/assets/25-public-safety-at-low-head-dams.pdf

I was paddling on the Delaware and Raritan Canal which parallels the Millstone River about two miles from where the dam is located at the confluence of the Millstone and Raritan rivers. This was a training session for a cold water canoe race that takes place each April in Maine. I am an experienced paddler, familiar with cold water immersion and so was wearing a wet suit with a dry top and pants along with a life jacket/pfd while on the calm water in the canal.

As I neared the end of my trip at the Manville causeway, several police cars slowly drove by and turned around as if searching for something. Sirens were wailing and more police and rescue vehicles were seen and the road blocked off. First thought was the body of a woman who was reported to have ended her life in the Millstone a week before was found.

As it turned out a kayaker and two companions in a canoe decided to run the dam. According to my recollection of the news article; the canoe made it through first, while the kayaker who followed, failed to clear the dam and was stuck in the hydraulic.

According to the news article, ‘the experienced paddlers’ wore no thermal protection or pfds when they ran the dangerous dam. It was reported that the canoers paddled back to help their companion and they capsized in the hydraulic. Once you cross that line which marks the downstream flow from the water cycling upstream, you will be pulled into the hydraulic.

The kayaker and one of the men in the canoe were washed out of the turbulent water but the other was lost, his body never recovered.

A hydraulic occurs when the weight of falling water creates a hole which is then filled by downstream water being pulled upstream in an endless re-circulating current parallel to the dam. Low head dams may be altered to prevent or mitigate a hydraulic.

There is a point of no return where you can actually see a line that separates the water flowing downstream from the water flowing back upstream to power the hydraulic.

Island Weir Dam at the confluence of the millstone and Raritan River. You can see the horizontal shelves that are the fish ladder in the center and the subsequent stepped redesign to mitigate the dangerous hydraulic.

There have been several more drownings involving dams on the Raritan and its branches. I recall another at the Headgate, which is the dam created by the Duke estate below the confluence of the North and South branches. The paddler went over and was lost in the hydraulic below.

This is the headgate dam at Dukes Island Park. Created to collect river water via the Dukes canal to power the estates and supply water to the series of ponds built at decreasing elevations to allow the water to return to the river by gravity.

No warning signs are posted to alert paddlers to the danger ahead. On the downstream face of the dam is a warning to keep off.

Too little too late warning.

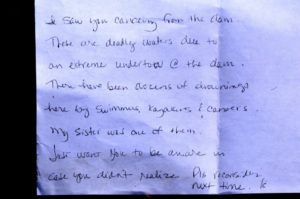

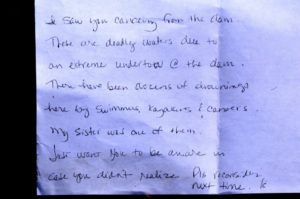

Paddling on the South Branch from Rockafellow’s mill rd, just below the low head dam that forms Red Rock Lake, this note was placed on my windshield. Though I was no where near the dam, contrary to what the note states, the message was at once heart breaking and shown here, now serves as a warning to all; beware of the dangers of low head dams.

This sign is placed about 5 football fields above the dam at red rock lake on the South Branch. It’s placement a puzzlement that mitigates its message.

Dam at Red Rock Lake.

Though rivers like the South Branch and North Branch are reputed to be no more dangerous than a swimming pool, tragedy can strike when least expected. Strainers, trees that fall into the river blocking passage, can snag and capsize a boat and entangle the paddler in its branches under pressure of a fast current. Low head dams can drown a paddler by immersion or entanglement on debris as the paddler is unable to wash out of the turbulent recycling water. Search on line to get an idea of how widespread is the danger of obscure low head dams and loss of life across the country.

Paddling when river temperatures are well below normal body temperature requires thermal protection no matter the air temperature. Wearing a pfd alone will not be enough to survive if your body temperature drops before you can be rescued or self rescue. Such was the case of a paddler on Round Valley reservoir a few years ago.

Typically water temp during the winter and early spring on the South Branch is 41 degrees. More than enough to cause a spasm to block your ability to breathe even before hypothermia sets in. See this link for a detailed explanation of the effects of cold water immersion. Remember, ‘cold water’ does not have to be that cold.

http://www.coldwatersafety.org/ColdShock.html

Overturning in fast water, a boat can instantly fill with a hundred gallons of water. Each gallon weighing 8 pounds, can pin or crush a paddler between the canoe and any obstruction. Such was the case on a locally sponsored canoe trip in shallow water on a beautiful day on the South Branch. One paddler was trapped under the canoe in a strainer. Eventually he popped out from under the boat, shaken but safe. The canoe was stuck fast in the strainer, filled with hundreds of pounds of water. Never be downstream of a capsized canoe.

Tragedy can occur on the calmest day under brilliant blue skies, always wear a pfd and be alert to potential dangers, especially dams.

Low head dam across the North Branch just above rt 202 makes a difficult passage during low water portage and a dangerous hydraulic during high water.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.