Meet LRWP Board Member David Tulloch

Interview by TaeHo Lee, Rutgers Raritan Scholar

On the second Monday of 2019, LRWP Board Member and Rutgers Professor David Tulloch welcomed me to his office at the Center for Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis lab (CRSSA). Giant maps on the lab walls hint at what Professor Tulloch does at Rutgers. His research focuses on a mixture of landscape architecture and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Professor Tulloch received a Bachelor’s degree in Landscape Architecture at the University of Kentucky, his Master’s in Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University, and PhD in Land Resources at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He has now lived and worked in the Lower Raritan Watershed for two decades. He enjoys exploring our area on foot, urban hikes, and trying to connect pieces of landscapes that a lot of people overlook. These interests led him to create an interactive google map that explores various features of the Lower Raritan Watershed. The map will soon be a supplement for Professor Tulloch’s “Watershed Highlights and Hidden Streams: Walking Tours of the Lower Raritan Watershed,” which kicks off on Sunday March 16.

TaeHo Lee: Where are you from in the LRW, and in your time in the watershed, how have you engaged in/explored the watershed?

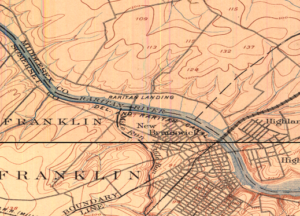

David Tulloch: I live in Highland Park near the Mill Brook, and I have lived there for nearly 20 years. I am within an easy walk to the Raritan making it hard to ignore the connection of the landscape and its watershed to the river. I’ve gotten to know the watershed as I explored it not only as a person who is curious about the large landscape. But also, as a benefit of my job, I have what amounts to two decades of mapping and design projects in different parts of the LRW and the larger Raritan River basin. Student research projects and studios have helped me get to know the watershed in ways that now are quite helpful in ways that, at the time, I didn’t always appreciate. My favorite thing to do in the Watershed is just to get out and walk it. I will look through historic maps or various air photos and look for hidden connections to explore. But there are also plenty of marked trails within the Watershed that I have yet to walk.

TL: As a parent, how do you want your kids to engage in/with the watershed?

DT: Well, I want my kids, like so many people who have grown up here, to really treasure this as a special landscape and see that it is both a special landscape and a singular, very large landscape. It has a fascinating history that we don’t talk enough about: American history, Revolutionary War, World War II, and an industrial history which is really significant as it impacted people around the world but also has impacted the river and our communities pretty dramatically. There are interesting educational and cultural histories for example, a colonial college right on the banks of the river in New Brunswick, the old proprietary house in Perth Amboy, the Monmouth Battlefield. So many things have marked this landscape. Additionally, its nature is incredible: Bald eagles, peregrine falcons, sandhill cranes, all within a few miles of us. And the landscapes that make up the Watershed are amazing: Mountains to marshes with really special spots within the Watershed like Duke Farms, Watchung Reservation, and the Rutgers Ecological Preserve. I really hope that my sons are coming to see the place not just as memorable but as incredibly special and something to treasure, even if they end up in another part of the world in the coming years.

TL. What, in your view, are the primary issues that need to be addressed in the watershed?

DT: The first for me is clearly the need to improve resident’s awareness of the Watershed and its issues, and their understanding of how both natural and policy processes within the Watershed work. I think one of the real challenges for us, an issue that affects ultimately the quality of water of the river, is encouraging our population of something like 800,000 residents to understand that the watershed is so much more than the river, and more than just the river valley. Most people associate the watershed with Donaldson Park, Johnson Park, Duke Island, or Duke Farms, and they can see those as areas that are associated with Raritan River. But we need to help them understand that in a 350 square mile watershed places like Freehold, Scotch Plains, and Bridgewater are all contributing to the water quality and the experiential quality of the watershed. And with a growing awareness and understanding, comes an appreciation of how much we still don’t know and how we need to enlarge our understanding of the river.

The other issue that really stands out to me is the land use of the watershed. It covers 350 square miles and includes 50 municipalities, each making their own independent decisions about land use with very little coordination, and we share collectively in the good and bad outcomes of these decisions. I live in one of those municipalities and work in another, but in between projects for work or taking my kids to different events I spend lots of time in other watershed towns experiencing the results of those independent decisions made in 50 different borough halls, city halls, and township halls. A really important step is to begin to monitor land use choices, and to examine them in terms of how they impact the watershed. We need to help the different people involved with the LRWP connect with those processes and see them in a more serious way.

TL. What is your vision for the LRWP?

DT: One important thing as a young organization, part of the shared vision we all have, is that as a growing organization it needs to be nimble enough to adjust to not only the changing needs of the Watershed but also the changing understanding of what the organization can become. Through listening and learning and reshaping itself, we all come to a new understanding of what the Lower Raritan Watershed as a community, as a physical landscape, and as a place with changing pressures on it, is.

Having said that, three areas are really important for us. One is appreciation. I don’t just mean that in the broadest sense, not just appreciating the place, but appreciation based on increased understanding. That’s getting more residents out on cleanups so they can see the problems themselves; getting as much as we can out of the research at Rutgers and the NJ DEP and from others working along the river so that our appreciation of those problems are also based on something serious.

Second is advocacy. My vision for LRWP sees it as a voice for the river and the Watershed that can really advocate for needs that often don’t have a strong voice.

Third is action. Turning the appreciation and advocacy into action. This includes small steps like cleanups, but some of the actions we take overtime can become more dramatic. Appreciation, advocacy and action, I think, together really represent a forward looking vision for the Watershed and the Partnership that could engage a very large number of residents and not just the usual suspects.

TL. You are a Professor at Rutgers. What is your role there? Can you provide insights into how we can best bring the resources and attention of the University to address the needs of the LRW?

DT: As a faculty member of Rutgers, I have formal roles. I am Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture, Associate Director at CRSSA, and lead the GeoHealth lab. A lot of the things that I do at Rutgers are as an integrator, as someone crossing over between different kinds of activities. So I work as an educator, and in landscape architecture I teach design, I teach planning, I teach what we call geomatics. But I’m also a researcher here at the center. We are looking a lot at the ways that the landscape is shaped and affects human health and our lives.

In my role as an integrator, I bring research into the classroom, and draw students back into the research. In the same way, I am now really interested in integrating the experiences with the watershed into the different activities that I have in Rutgers, as well. As part of my research 20 years ago or so, I visited and interviewed NGOs all over New Jersey, looking at their use of GIS and mapping. The groups that most caught my attention at the time were primarily watersheds. Many of them were brand new and in that way, for me, it was the first chance to learn and explore New Jersey’s landscapes. This forced me begin to confront the potential that Watershed organizations have as advocates for pieces of the landscape across municipal boundaries. I also began to see a role for integrating science and education and policy.

One of the other roles that I have at Rutgers is interacting with students. I get to know a lot of students as they first come to Rutgers. A role for me with students who are not from the area is helping them appreciate what a special place this is, getting them hooked on the River, and sharing Rutgers’ long relationship with the river. After all, it’s mentioned in the school song. In the broadest sense, to answer your question, we are so fortunate as a watershed organization to have a University like Rutgers in such an integral relationship with the river and the Watershed. But, with the many research and outreach programs that Rutgers has, one of my ongoing roles is going to be bridging the two and helping make connections with those activities and helping be a voice for the Watershed as well.

TL. I understand you are planning a series of “Walks in the Watershed.” Can you tell me more about this opportunity? What is your goal with the walks?

DT: Part of this goes back to simply trying to help all of us improve our appreciation and understanding of the watershed in little and big ways. But the walks are a very special way to connect the abstract places that we’ve all seen on maps with very real experiences on the ground. The goal with the “Watershed Highlights and Hidden Streams: Walking Tours of the Lower Raritan Watershed” is to help reveal connections across landscapes of the Watershed that are often hidden in plain sight, but also to help us explore some connections, like hidden streams, that are truly invisible.

Over time we will try some walks that explore the outer edges of the Watershed – Beyond the banks of the old Raritan – but at the start, we’re going to take walks that explore connections of important pieces of land to the river and, where possible, look into the streams that make those connections. So, one of the first walks, on March 17, is going to be close to the Rutgers campus here where we’ll be looking at the connections between Buell Brook and the Raritan by taking a walk that connects Johnson Park and some of its history and Raritan Landing with the Eco Preserve. Many people visit Rutgers’ Eco Preserve and don’t think, even when they are only hundreds of yards away from the river, don’t think of its connection to the river. The walks will look more at the connection and what it means. Walking also just reveals some other patterns and some hidden features along the way. I hope to be as surprised as the other participants. A second walk this Spring, scheduled for May 18, connects the old constructed landscapes of the canal at Duke Island County Park through a new greenway that has been developed along the Raritan and crosses over into the Duke Farms properties. I think a lot of the residents in that area are familiar with individual pieces. Fewer have made the walk to connect them all. We hope to make the walks a regular experience.

TL. Is there anything else you want to add?

DT: When you asked about what I do at Rutgers and how this helps make connections for the watershed, let me mention one more example. I think that as I teach planning students and geomatics students and design students who make some connection with the place, that the Watershed as a whole also is benefiting from those who stay here. An interesting example of that is Daryl Krasnuk, who I taught as an undergraduate student. Daryl has continued to volunteer and make maps both for the LRWP’s general education efforts and specifically for the State of the Lower Raritan Watershed report. It’s exciting to see the students that I taught now sharing their passion for this special place and finding ways to help up us to improve that landscape over time.