Article by Heather Fenyk, photo credit Salzburg Global Seminar/Katrin Kerschbaumer

Earlier this month I traveled to Salzburg, Austria to take part in the Salzburg Global Seminar Session “Building Healthy, Equitable Communities: The Role of Inclusive Urban Development and Investment.” I was invited to discuss the role of citizen science in watershed management and land use planning, and my presentation highlighted issues and opportunities in New Jersey’s Lower Raritan Watershed. More specifically, I linked the work of Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership volunteers who collect water quality data and map stormwater infrastructure with desired human and environmental health outcomes.

Salzburg Global Seminar “Data and Evaluation Round Table” Participants, October 2018

The Salzburg Global Seminars started in 1947 as an international forum for post-war healing. The intent was to bring global actors together to develop a “Marshall Plan of the Mind” as a critical element of post-war recovery. Seventy years on, Salzburg Global Seminars continues to nurture global networks of researchers, policy makers, activists and advocates around pressing issues and concerns. My cohort of 50+ Fellows from 16 countries joined together for a week of discussions on themes including:

How can we leverage trends and opportunities in urban revitalization with investments in infrastructure to focus on health, equity and the public good?

Are there key policy strategies or practices that support healthier and more equitable housing, transportation, utilities and park/open space/environmental systems?

How can we foster a shared sense of community in the built environment? Can that lead to infrastructure in the public interest?

Can, and how can, data and citizen science be used to direct resources and promote equitable development?

Seminar discussions were punctuated with case study presentations and problem solving “labs,” and we soon organized ourselves into working groups to develop theoretical statements, policy proposals, and frameworks for practice and action.

I was part of two working groups. One of the working groups, which included individuals from Hong Kong, New Zealand, Australia, Spain, Canada and the United States, set out to address immediate community needs related to the fragmentation of habitat in our built environments. This group designed a tool to map and prioritize underutilized community infrastructure for public multi-sharing/multi-functional use. The Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership plans to pilot the tool in the Lower Raritan Watershed in coming months. The other working group, which in addition to myself included individuals from India and Germany, developed a research agenda to address a gap in the literature related to health outcome assessments at the watershed level. Both groups have been asked to develop an issue brief for publication in a special issue of the British Medical Journal.

In addition to advancing research and action around healthy, equitable communities, Salzburg Global Seminars formed a global peer support network of Seminar Fellows – that is professional practitioners from around the world working in the built environment and health.

One easy-to-share tool our Salzburg Seminar Group developed is the fun 7-Days-of-Change guide, built around the United Nations Development goals!

While I am thrilled to be a part of this global initiative, I know there are also many in New Jersey and the Lower Raritan Watershed who are working to foster healthy, equitable communities. With an eye to advancing urban environmental restoration of our New Jersey landscape, and with the specific goal of marrying efforts to improve environmental and human health locally, I welcome conversations with folks who would like to create a New Jersey specific “Healthy, Equitable Communities” peer support network. Feel free to contact me at: hfenyk@lowerraritanwatershed.org

The LRWP is pleased to be part of Jersey Water Works, a collaborative effort of many diverse organizations and individuals who embrace the common purpose of transforming New Jersey’s inadequate water infrastructure by investing in sustainable, cost-effective solutions that provide communities with clean water and waterways; healthier, safer neighborhoods; local jobs; flood and climate resilience; and economic growth. The LRWP is active on the Green Infrastructure subcommittee.

Jersey Water Works recently published Our Water Transformed: An Action Agenda for New Jersey’s Water Infrastructure – check it out! And plan to join Jersey Water Works for their annual conference on December 7 at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark!

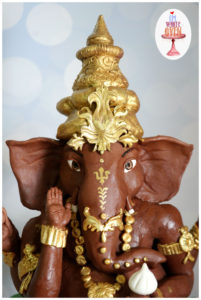

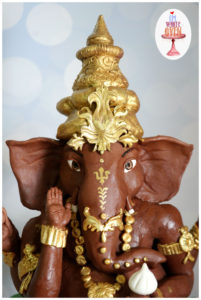

Ganesh Chaturthi – or Vinayaka Chaturthi, Chavath, or Lambodhara Piranalu depending on where you live – is one of the biggest Hindu festivals of the year. Occurring at the end of India’s four month monsoon season and at the beginning of the harvest season, Ganesh Chaturthi invokes the elephant-headed God Ganesh for a bountiful harvest.

There is a lovely environmental meaning to the Ganesh Chaturthi festival. Ganesh idols were originally fashioned from the clays of area water bodies prior to the monsoons so as to clean the waters of silt deposits. Part of the festival involves Ganesha devotees celebrating their local region’s natural history by gathering 21 symbolic non-agricultural medicinal plants for inclusion in an offering to the idol. Traditionally at the end of the festival the idols were returned to waters from which their materials were taken, often with the plant and other offerings.

Ganesha and 21 leaves offerings – from www.thespiritualindian.com

In the past decades, Ganesha idols in India and the United States have been constructed out of non-biodegradable Plaster of Paris, plastic or metal, and painted with toxic paints. And it is often the case that idols are abandoned in rivers, lakes, streams or the ocean at the end of the festival. These idols can take several years to fully dissolve, if they dissolve at all. This leads to lowering of oxygen levels and contamination of our water bodies. Unfortunately the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and partners have found many dozen abandoned idols in area waters over the years.

Ganesha idols found in the Raritan River on September 20, 2018

As the negative environmental impacts of abandonment of Ganesh have been recognized, practices have been adopted to minimize these impacts. Increasingly clay and mud idols are crafted with a seed inside them, painted with non-toxic rice paste and vermillion, and then buried or planted in home gardens instead of being immersed or abandoned in area waters. We have also heard about a new way of making the Ganesha idol: that is by using modeling chocolate. The Ganesha idol is made using chocolate, and at the end of the festival the idol is immersed in milk. The chocolate is then distributed among celebrants, or provided to the homeless.

Chocolate Ganesha – it dissolves in milk!

In the United States it is a violation of the Federal Clean Water Act to pollute or discharge ANY items (biodegradable or otherwise) into waterways without a permit. It is now the case that many Hindu temples and other other cultural institutions secure permits for temporary immersion of the idols in the Raritan River and area streams. That is, celebrants bring their Ganesha to a public ceremonial immersion event and then reuse their idols the following year. We applaud those who celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi in an environmentally friendly fashion.

For those who celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi we wish you happiness as big as Ganesh’s appetite, life as long as his trunk, trouble as small as his mouse, moments as sweet as modaks, and a healthy and clean environment in which to honor Ganapati and his gifts. Happy Ganesh Chaturthi!

Article and photos by Joe Mish

Shades of fluorescent orange, used to color the dawning day, dripped from the palette of the celestial artist to set the autumn woods on fire.

Shades of fluorescent orange, used to color the dawning day, dripped from the palette of the celestial artist to set the autumn woods on fire.

Waves of celestial orange roll over the treetops to set the autumn woods ablaze.

The white, early morning autumn mist hung motionless above the flowing dark water of the South Branch. As dawn approached, the rising sun turned the eastern horizon into a glowing red-hot coal that lit the pale mist with an orange blush.

The trees along the river were immersed in the flood of pre-dawn mist. Some completely hidden and others partially protruding as dark brown silhouettes floating adrift on a misty sea.

As the sun arose, it was as if watching an artist at work laying base colors and adding tints to bring a charcoal sketch to life. The changing light and rising temperature caused the orange mist to vanish as entire trees appeared from the mist, revealing splotches of vibrant fall color.

It is easy to imagine the changing colors of the sunrise were infused into the river mist to wash over the treetops and set their leaves ablaze.

The same spectrum of color seen in the eastern sky at dawn can be found in the fall foliage not flooded by river mist. The full visible spectrum from violet through red and orange, to pink, salmon and yellow are shared as the tree tops meet the sky’s loaded paint brush.

A mere splash of color in early autumn is all that is needed to set the late October woods ablaze. Each living drop of color slowly expands to cover the entire leaf as the season progresses. Its radiance now sets adjoining leaves aglow until the entire woodland canopy is bathed in bright color.

Retreating skyward to a time lapsed satellite view, the expanding colors can actually be seen migrating south. The green foliage appears to be consumed by the advancing flames of the autumnal fire.

Poetic inspiration imagines it is the weight of intense color that causes the leaf to depart the branch.

Gusts of wind stir the treetops to recruit a shower of shimmering color in a free fall final dance for which the tethered leaves had been rehearsing since spring.

The first leaves to fall are contributed by the black walnut and ash trees. Impatient for some reason to drop their leaves. They stand naked among the still well-dressed oak and maple associates just beginning to change color.

A stand of Norway maples grew thick along a low ridge that bordered a sloping cornfield. Their brilliant yellow leaves carpeted the ground and reflected light upward to brighten the understory and set the leaves aglow. The lowest leaves fought for their share of light all season and grew oversized in the effort. The reflected light penetrated the deep shade to illuminate these outsized yellow beacons to celebrity status.

The change of leaf color during autumn has a well-established scientific explanation. Though a longer held belief declared, without question, the color was the work of an ethereal magician.

It is easy to subscribe to that belief when you see a green leaf turn fluorescent orange, a color otherwise unknown in nature. The only place to see that color was in the flames of a fire or in the distant heavens to mark the sun’s arrival and departure.

The fall color is best seen as magic, to set your imagination free and escape to a quiet place where all things are possible.

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article and Photos by Margo Persin, Rutgers Environmental Steward

Editor’s Note: In 2018 Margo Persin joined the Rutgers Environmental Steward program for training in the important environmental issues affecting New Jersey. Program participants are trained to tackle local environmental problems through a service project. As part of Margo’s service project she chose to conduct assessments of a local stream for a year, and to provide the data she gathered to the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership (LRWP). Margo keeps a journal of her experiences, excerpts of which are included in the LRWP’s “Voices of the Watershed” column.

Internship Diary / August, 2018

For this visit to my assigned assessment site, I had new members of my ‘team’. It so happens that two of my godsons were visiting from London, UK, where they reside and go to school. Alex, 14 years old, and Mathieu, 12 years old, were presented with the option of participating as full team members to do a stream assessment at the Ambrose Brook. They readily agreed, and we set off for the stream site.

The day was partly cloudy upon arrival and proceeded to get more clouded over as our time at the stream advanced. I appreciated very much the extra eyes and hands, given that it would take a group effort to undertake and finish all the measurements required of the assessment. It was so nice to have the company and the opportunity to share this activity with them. They asked some pertinent questions in regard to the site, as well as concerning the focus of the project. We were armed with marker flags, tape measure and ruler, thermometer, stop watch, and the required forms to fill out. In addition, as a nod to my own childhood, I had dug out of storage the red plastic duckie that I had used so (too) many years ago when I was a child. After having sealed the seams with glue, it proved to be water ready and floatable, and was thrown into our equipment bag.

Upon arrival, we did a quick survey of the site. I gave the boys an overview of the project as we walked the required distance to mark off where we would take our measurements and set our marker flags. We were not particularly surprised to note that summer was on the wane, and the stream site showed the effects of the copious summer rain fall of this year and the subtle yet visible march of time on the greenery. There were a few trees already beginning to drop some leaves, apparent at their base as well as at the edges of the stream. Some windfallen branches had made their way into the stream on both sides, evidence of the frequent storms that had buffeted our area during the preceding summer months. In addition, the water level had risen, as marked by mud splashes on bushes, trunks and the mud banks. There were a few ducks and Canadian geese, who had vacated the surrounding lawns and walkways; that day, they were floating lazily on the water’s surface between the far bank and the island, oblivious to our presence.

Ambrose Brook, August 2018 – Margo Persin

High water at Ambrose Brook, August 2018 – Margo Persin

At that point, the boys and I got to work. Alex and I did the physical measuring, including wading to the middle of the stream to measure depth and velocity, while Mathieu took on the role of scribe and stop watch handler. The first order of business was to observe, consult and come to a shared decision in regard to water conditions. My team mates took their jobs seriously and we were able to arrive at mutually acceptable readings of turbidity and stream flow. The next order of business was to measure width, depth and velocity. Armed with the rubber duck and ruler, Alex waded to the starting point while I headed in the opposite direction. Mathieu had been instructed in the subtleties of the stop watch, and as the two of us with wet feet called out the various measurements and Mathieu proceeded to fill out the form. All of us – Alex, Mathieu, me, and the rubber duck – showed ourselves up to the task and we were able to finish that part of the assessment in due time.

After exiting the stream, it began to rain, so the three of us made a mad dash back to my vehicle, where we took refuge and worked through the rest of the form. The boys were more than willing to express their views in regard to stream characteristics as well as all the elements of high gradient monitoring. We reviewed the results in order to make sure that we were of one accord in regard to our observations and conclusions. They did a wonderful job of giving themselves over to the project, with determination, seriousness, intellectual curiosity, good humor, and dedication. After approximately one and half hours, we took our leave and headed to a nearby ice cream parlor for a well-deserved reward. Their company and participation were most welcome and I hope that this experience will inspire in them the desire to become involved with environmental projects of their own, whether on their own or in conjunction with their school curriculum.

Article by Maya Fenyk (age 14), photos by Joe Mish and Karen Byrne

Sedge Island Field Experience youth after relocating an osprey nest, photo by Karen Byrne

In mid-August I had the opportunity to be part of the Sedge Island Field Experience (SIFE), a program run by the New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife. Through SIFE I learned about the ecology and history of the marshes in the Barnegat Bay Area, and to study the area’s wildlife including birds and bugs. At the end of SIFE, campers have an opportunity to present what they have learned throughout the week on topics of their choice. I chose to do a presentation on a threatened species that is found in both the Barnegat Bay area and in the Lower Raritan Watershed, osprey.

Osprey are beautiful and distinctive birds, with brown feathers covering their back and wings and white feathers covering their stomach. Their heads are also a brilliant white, with a dark eye mask (similar to a raccoons). The osprey are also very big birds, with their height being typically 21-24 inches and their wingspan being 4 feet 6 inches-6 feet. Their voice is also distinctive, loud, high pitched and musical, like a cheeep cheep cheep.

Osprey, photo by Joe Mish

Osprey are not only beautiful birds but they are extremely important to every area they inhabit because they are an indicator species. An indicator species is a species that indicates the level of pollutants in different areas just by where they choose to make their homes. Since indicator species are very pollution sensitive, they won’t choose to live in an area where there is a lot of pollution. In this way they indicate that the level of pollution in the areas they inhabit are fairly clean. Where ospreys choose not to make their homes also indicates the level of pollutants because if there is an area that historically has been the osprey’s home, and osprey are not found there, we know that something is telling the osprey to stay away. Once we know that something is wrong, environmental conservation agencies can then determine the cause and hopefully bring the osprey’s back once the problem is fixed.

Osprey are a migrating species and have a range which spreads across the entire continental United States, the majority of Central and South America and some of Canada. Ospreys make New Jersey their home during their breeding season, which extends from April- August. After breeding season they begin their long trek to Central and South America to countries such as Ecuador and Colombia where they spend their winter.

Unfortunately, ospreys are less common in New Jersey than they used to be prior to the development of their habitat and the inadvertent poisoning of them in the 50’s and 60’s due to the use of the pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), used for mosquito control. Though osprey did not consume the pesticide directly, they were poisoned through the process of biomagnification. What this means is that when mosquitoes were treated by DDT, fish then consumed the treated mosquitoes, ingesting DDT themselves. Then when the osprey consumed the fish the concentrated DDT affected them as well. Every time an animal consumed another animal the amount each animal consumed was magnified exponentially. Another effect that DDT had on osprey was that it made their eggshells very brittle and thin so that when the mother osprey went to sit on her eggs, they would break, killing the unborn hatchling.

In 1974 there were only 50 active osprey nests in the state of New Jersey, and that was the point when the New Jersey Department of Fish and Game (now New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife), through a program led by Paul D. “Pete ”McClain stepped in. The program brought hatchlings and breeding pairs from Maryland to the Barnegat Bay area to increase the population in New Jersey. The osprey are now protected through State and Federal Laws. They have been taken off the endangered species list and moved to the threatened species list. Forty years ago there were only 50 breeding pairs in New Jersey, but there are now 700 breeding pairs, including many juveniles. Even though the osprey are out of immediate danger, they still need to be protected and their habitats still need to be conserved. Many threats still face the osprey and only 50% of juvenile osprey live to adulthood.

So, what are people doing today to protect the osprey? During my SIFE week I had an opportunity to work to protect the osprey.

Due to the development of their habitat in the Barnegat Bay area, specifically creation of a canal that removed their roosting lands, the osprey now must live in man-made platforms. Through the SIFE program I had the opportunity to relocate an osprey nest from direct contact with an kayak/canoe trail to a place with more limited human contact. The New Jersey Department of Fish and Wildlife was concerned that the prolonged contact with humans through the osprey nest being on a trail would lead to the abandonment of that nest and thereby decreasing Barnegat Bay’s population of osprey. See the photos below for a visual story of how our group relocated an osprey nest.

The day after we moved the osprey roost, osprey had already moved in, seemingly happy with their relocated home. I was extremely lucky to have the opportunity to help the osprey in such a way, and I recognize that not every can do that, so I encourage everyone to find their own way to help ospreys like making sure that their environment is clean and even donating to organizations who are monitoring and taking care of the osprey. Everyone can help get the osprey off the threatened species list, what are you going to do to help?

Sedge Island Field Experience youth move an osprey nest, photos by Karen Byrne

Article by Joseph Mish, photos by Joseph Mish and Brian Zarate

A moment in the sun. The elusive and rare bog turtle, aka Muhlenberg turtle, is captured in this image by Brian Zarate.

The smallest and rarest turtle in NJ has emerged from the obscurity of its muddy bog to celebrity status as the bog turtle was recently named New Jersey’s state reptile.

The bog turtle was first scientifically cataloged by botanist Gotthilf Muhlenberg at the approach of the 19th century. In honor of the discoverer, this diminutive reptile was named Clemmys muhlenbergii. It was commonly known as the Muhlenberg turtle until the vagaries of taxonomic nuance christened it the bog turtle, one hundred and fifty-six years later.

The bog turtle averages a bit less than four inches in length. To visualize its size, write its scientific name on a piece of paper and that length will approximate the size of the turtle.

The blaze orange patch on the side of its head provides unmistakable and instant identification. The orange color glows like a brilliant gem. Stare at it for a moment and the turtle magically materializes from its muddy background.

The overall appearance of the turtle is a grayish black, though on closer inspection there are varying degrees of dull orange skin and freckles especially at the base of the front legs, neck and face. The carapace or ‘top shell’ is covered by ridged scutes or horny segments, comparable to fingernails. Faint amber markings may sometimes be seen on the shell, their appearance dependent on age or accumulated mud.

The small size, secretive habits and specialized habitat requirements restrict the presence of this turtle to very defined regions of the state.

As its name suggest, these turtles prefer open boggy areas fed by clear springs or streams. Skunk cabbage and jewelweed, aka, ‘touch me not’, are easily identifiable plants commonly found in bog turtle habitat. Pasture lands are desirable locations as plants and grasses are kept in check by grazing cows to maintain optimum preferred habitat. Deep mud, constantly infused with spring water, provides ideal hiding places and protection from freezing during winter hibernation.

Tree stumps protruding from the bog and raised islands are preferred locations to lay eggs. Females seek these drier places within the bog to lay eggs as opposed to other turtle species which travel quite far from home.

To illustrate the secret life of the bog turtle, a friend who was a conservation officer, stopped to investigate a car parked alongside a road in north Jersey. He came upon two researchers following signals from a bog turtle equipped with a transmitter as part of a study project. Nothing could be seen to indicate a turtle was present. The signal, however, indicated its precise location and after digging deeply into the mud, there was the turtle alive and well!

Bog turtles are considered to one of the rarest turtle species in the United States.

The bog turtle had been declared ‘endangered’ by the state in 1974 and ‘threatened’ by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1997. Population estimates are speculative, as some articles cite the total population in the eastern US as 2,500 to 10,000 and ‘fewer than 2,000’ turtles in NJ. The Bog Turtle Project states 168 colonies have been identified. Equal distribution of 2,000 turtles over 168 locations cannot be assumed and further emphasizes the rarity of this precious gem.

Among the locations identified, there are a select few, which have a large enough gene pool to ensure a viable population into the future. While turtles found in isolated micro habitats are vulnerable to insufficient genetic variation.

In both situations the loss of contiguous habitat is a deadly threat, as a segmented environment limits migration and thus genetic variation as well as exposing animals to predators, mowers and vehicles.

Loss of habitat is a major threat to bog turtles as well as many other species.

Invasive plants, like the familiar purple loosetrife and phragmites, dominate areas to destroy plant diversity and alter soil porosity which in turn eliminates the cascade of insect and invertebrate life upon which the bog turtle feeds.

purple loosestrife invasive plant chokes out native grasses reduces invertebrate diversity

More turtles may yet be found by wild chance, though by no means can their presence be considered widespread as is the case with more common species like painted and snapping turtles.

Suffice to say the description of ‘rare’ is understated when used to describe the bog turtle.

The designation of ‘state reptile’ is not an endearing term to the general population. I like to think of the bog turtle, as one in a series, of New Jersey’s unheralded natural treasures.

Read about the NJ Bog Turtle project at

https://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/bogturt.htm

More references for bog turtle information.

https://www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/ensp/pdf/end-thrtened/bogtrtl.pdf

http://www.conservewildlifenj.org/species/fieldguide/view/Glyptemys%20muhlenbergii/

Should you find a bog turtle, report it and keep the location secret, as this turtle is high on the list of the illegal wildlife trade.

Report any discovery to the state at: https://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/ensp/rprtform.htm

Whenever I see a turtle, I always wonder how old it might be and compare it to events in my life. Most age ranges provided for wild creatures are speculative and based on captive animals or hard data collected from tagged wild animals. A bog turtle tagged in 1974 and estimated to be about 30 plus years at the time was again found in 2017, which places its estimated age at around 65 – 70 years old! That age range allows young and old to ponder what was going on in their life at any point in that turtle’s parallel life.

Thirty something years ago when that turtle burrowed deep into the mud to hibernate, my daughter was born in Muhlenberg hospital. A local hospital named after the son of the discoverer of the bog turtle, aka Muhlenberg turtle. The legislation to proclaim the bog turtle the official state reptile was co-sponsored by Kip Bateman of Branchburg. It would be a further coincidence to find and report the discovery of a bog turtle community within Branchburg!

Author Joe Mish has been running wild in New Jersey since childhood when he found ways to escape his mother’s watchful eyes. He continues to trek the swamps, rivers and thickets seeking to share, with the residents and visitors, all of the state’s natural beauty hidden within full view. To read more of his writing and view more of his gorgeous photographs visit Winter Bear Rising, his wordpress blog. Joe’s series “Nature on the Raritan, Hidden in Plain View” runs monthly as part of the LRWP “Voices of the Watershed” series. Writing and photos used with permission from the author.

Article by LRWP intern Daniel Cohen

The Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) is looking for volunteer weather observers in the Raritan Basin. CoCoRaHS is a nationwide volunteer precipitation-observing network, with over 15,000 active observers in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, Canada, the Bahamas, and the US Virgin Islands, including over 250 in New Jersey. The NJ program is run out of the Office of the NJ State Climatologist at Rutgers University. Working with the Rutgers Sustainable Raritan River Initiative, NJ CoCoRaHS is looking to enlist volunteers of all ages within the basin. Volunteers take a few minutes each day to report the amount of rain or snow that has fallen in their backyards. All that is required to participate is a 4″ diameter plastic rain gauge, a ruler to measure snow, a computer or cell phone, and most importantly, the desire to report weather conditions.

Observations from CoCoRaHS volunteers are widely used by scientists and agencies whose decisions depend on timely and high-quality precipitation data. For example, hydrologists and meteorologists use the data to warn about the potential impacts of flood and drought within the Raritan Basin.

“Weather matters to everybody –meteorologists, car and crop insurance companies, outdoor enthusiasts and homeowners,” according to CoCoRaHS founder and national director Nolan Doesken. “Precipitation is perhaps the most important, but also the most highly variable element of our climate.”

As Dave Robinson, NJ State Climatologist and NJ CoCoRaHS co-coordinator, notes, “The addition of new observers in your community will provide a detailed picture of rain and snowfall patterns to assist with critical weather-related decision making.”

“Rainfall amounts vary from one street to the next,” says Doesken. “It is wonderful having large numbers of enthusiastic volunteers and literally thousands of rain gauges to help track storms. We learn something new every day, and every volunteer makes a significant scientific contribution.”

CoCoRaHS volunteers are asked to read their rain gauge or measure any snowfall at the same time each day (preferably between 5 and 9 AM). Measurements are then entered by the observer on the CoCoRaHS website where they can be viewed in tables and maps. Training is provided for CoCoRaHS observers, either through online training modules, or preferably in group training sessions that are held at different locations around NJ.

“Anyone interested in signing up or learning more about the program can visit the CoCoRaHS website at http://www.cocorahs.org,” says Mathieu Gerbush, Assistant NJ State Climatologist and program co-coordinator. “We’re looking forward to welcoming new volunteers into the NJ CoCoRaHS program.”

For more information, contact the NJ CoCoRaHS state coordinators:

Dr. David Robinson, Rutgers University, drobins@rci.rutgers.edu, 848-445-4741

Mr. Mathieu Gerbush, Rutgers University, njcocorahs@climate.rutgers.edu, 848-445-3076

Article by Rutgers Raritan Scholar Intern Allie Oross

#lookfortheriver

On Saturday, July 7th, the LRWP led the New Brunswick Environmental Commission and other members of the New Brunswick community in a project on the Redmond Street side of Lord Stirling Elementary School. The final product of their hard work is manifested in a whimsical sidewalk mural that not only serves as a form of neighborhood beautification, but also a semi-permanent reminder of the intricate roles human’s play in the environment.

New Brunswick Environmental Commissioners, residents and LRWP friends paint flowers

Funded through an Americorps alumni grant secured by Thalya Reyes, and designed by former Americorps alum Johnny Malpica, interwoven swirls paint a picture of natural necessities that are integral aspects in every single person’s day to day life. In the mural, clouds create rain drops that collect to form a pulsing river. That river then flows into a set of flowers being pollinated by a bee and a butterfly with the next section displaying a fish in the river. Though the images are depicted in a delightfully playful and abstract manner, each can also be interpreted as a representation for a much more crucial concept:

We, as a community and as a species, must never forget how inextricable we are from the environment. You cannot have one without the other, and though we may seem separated from nature, the gap is almost always smaller than we may think.

New Brunswick Environmental Commissioner Howie Swerdloff paints a river

A few blocks down from the sidewalk mural is the Raritan River. A core purpose for the mural is to act as an expression of the course stormwater runoff takes through the New Brunswick streets every time it rains. After rain events our streets often serve as veins pumping litter and pollution into the heart of our waterways. Out of sight should never mean out of mind when discussing the environment, and the mural engages citizens to remember there is nature all around us if we only make the effort to search for it.

Article and Photos by Margo Persin, Rutgers Environmental Steward

Internship Diary / June, 2018

So summer is in full swing – I made a visit to the Ambrose Brook immediately after the summer solstice, on 24 June 2018. The environs have changed in several ways, both passive and active. There are several aerating fountains that spray a cool mist that is distributed by the shifting breezes off the water. The highwater mark on the center island has changed since I last visited, probably because of late spring run-off. But the water has even been higher, as evidenced by the residue on all of the banks, the tree roots that extend into the water, and the low-lying bushes. All are wearing a dusty mud color that gives evidence of water that has since receded. Water flow has significantly strengthened, as is noticeable over the modest waterfall close to Rte. 28. In addition, the rain run-off in the two drains has increased, so that more than a trickle from both of them is observable as it enters the brook after the waterfall.

Fauna have increased. One of my prize observations was that of a somewhat lazy or perhaps sleepy but wary blue heron standing on just one leg somewhat in the middle of the stream, past the waterfall. I tried to ease my way in a stealthy and languorous manner along the bank to not call attention to myself, but alas, the heron quickly reacted to my not so subtle approach, was on to me as I slowly worked my way toward the lovely bird . S/he dropped the second leg into the water, turned a cold shoulder in my direction, then deliberately moved away from where I had planted myself on the bank opposite to his/her position. Even though the distance between us stayed about the same, I was so taken by the proximity of this lovely creature and my ability to observe without causing a startled reaction. S/he continued a slow and deliberate saunter down the creek and disappeared around the bend. What a treat to be able to be a silent observer of a stream visitor. Nice!

I also noted that the population of Canadian geese has multiplied to a startling extent. And the birds have become so accustomed to human presence that they barely move when a vertical mammal saunters among them, even when they are settled down and roosting on the grass, the available paths or the cement. In order not to encourage their presence, the township has placed signs that pointedly give the command NOT to feed the waterfowl. Obviously, they greatly outnumber any other visitors to this place, either animal or human. And needless to say, mementos and tokens of their presence are all around, some pleasant and others not so much. An addition to the command to not feed the waterfowl would be “Watch your step and be sure to check your shoes before getting in your vehicle.”

Another observation is that butterflies and moths inhabit the environs, with several Monarchs making their graceful presence known as they fluttered past and through my line of vision. Their wingbeats cast a silent beat to the pulse of the planet as they made their way over and through the environs.

Human presence has also increased. It should be noted that the four walkways that run over and parallel to the stream offer an unobstructed view. And all of them are handicap accessible either all or in part. In other words, on all of them ramps are available so that proximity to the stream can be achieved. People who are fishing on the walkways are only part of the traffic. There were several runners, families with tots and strollers, and other quiet observers to finish out the panorama. My next visit in July will be for another stream assessment, boots, thermometer, floating duck, ruler at the ready Happy summer, everyone!